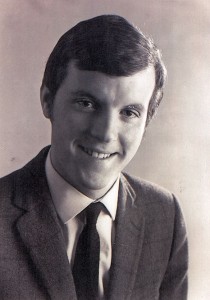

Malcolm Rennie, 28, from Neilston, Scotland, was murdered on October 16, 1975, by the Indonesian military in East Timor. Image courtesy campaigners.

As a young reporter starting at the Barrhead News more than a decade ago, I got a phone call or letter in the mail – I can’t remember which now – about the murder of a reporter from Neilston, East Renfrewshire, on my patch.

Malcolm Rennie was 28 when he was killed during a “terror-and-destabilisation” campaign by the Indonesian military in East Timor. He and four colleagues with Australian TV were brutally shot and stabbed, then mocked up to look like armed and legitimate targets, and then supposedly victims of crossfire between opposing forces.

It was neither. It was murder, and in 2007, after years of delays and campaigning by families, a New South Wales coronial inquest heard from 66 witnesses and concluded that the five men were “shot and/or stabbed deliberately, and not in the heat of battle, by members of the Indonesian Special Forces, including Christoforus da Silva and Captain Yunus Yosfiah on the orders of Captain Yosfiah”. The government was advised that Australia had jurisdiction to prosecute. It has not. The UN has also refused to issue arrest warrants.

Rennie, Brian Peters, from Bristol, and Australians Greg Shackleton and Tony Stewart, and New Zealander Gary Cunningham are today remembered as the Balibo Five, for the town where they were killed on October 16, 1975. A film, Balibo, was made in 2009 and is widely available.

These men were not the only reporters killed in East Timor – Roger East in December 1975 and Financial Times reporter Sander Thoenes in 1999 were also victims of Indonesian forces. And all, for their efforts, are remembered by people of what is now the independent Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste.

Why do the people of Timor-Leste remember when many beyond that corner of the world do not? Because the reporters were carrying out some of the most important roles journalists have: as witnesses, as investigators, and as comforters of the afflicted.

The classic US journalism line is “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable”. But when I wrote the core principles for Tomorrow, I amended it to “afflict the complacent”, because complacency is what allowed Indonesian occupation of Timor-Leste for a quarter century. It is what allows those responsible for anywhere from 100,000 to 200,000 civilian deaths – potentially one in three of the population – to evade justice. And complacency allows the reporters of the start of that invasion and everything that happened after to be forgotten.

As a reporter, and admittedly a very comfortable one compared to those who throw themselves into war zones, I feel the deaths of my colleagues because they were doing what is, at its best, more than just a job. Being a reporter is who you are, bearing witness, comforting the afflicted and afflicting the complacent – those course through our veins.

And so I remember Malcolm Rennie today. And I remember his colleagues. And I remind myself why journalism matters.

But behind all journalism is people. And I give the final words to Margaret Wilson, one of Malcolm’s cousins and someone still fighting for justice.

“We are very aware of the significance of this anniversary, and I wish I could tell you that there is progress being made towards achieving justice, but I really can’t,” she told me by email.

“I think people should, and must, still care, because this remains of the most blatant examples of political and commercial expediency trouncing human rights. This administration made all the right noises over the Charlie Hebdo affair, but when I wrote to the Prime Minister [David Cameron] to applaud his support of journalistic freedom and condemnation of violence to suppress it, and to remind him that a similar outrage concerning British citizens had gone unpunished for 39 years, all I got in reply was a standard note from a civil servant thanking me for my letter.

“At the moment, we are in contact with the Foreign Office and have been promised to be put in touch with a British police liaison officer, with a view to the police here considering the feasibility of pursuing a prosecution here, but this is a painfully slow process.”