How a largely forgotten group of men in World War I would shape a century of indigenous relations in Canada

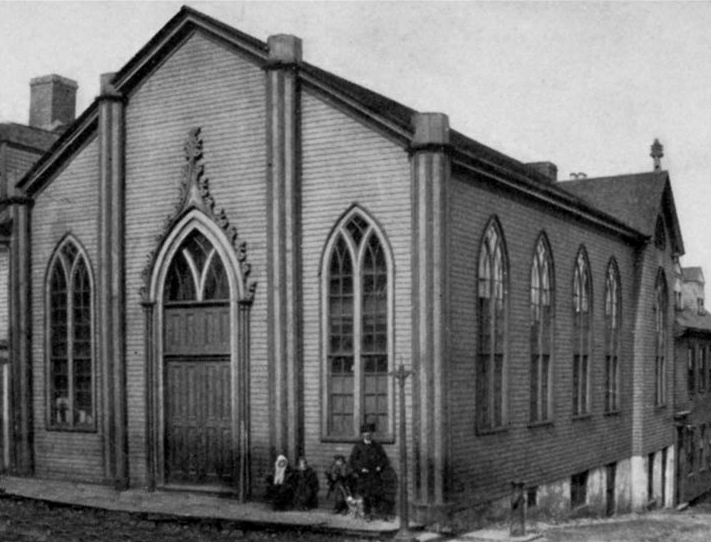

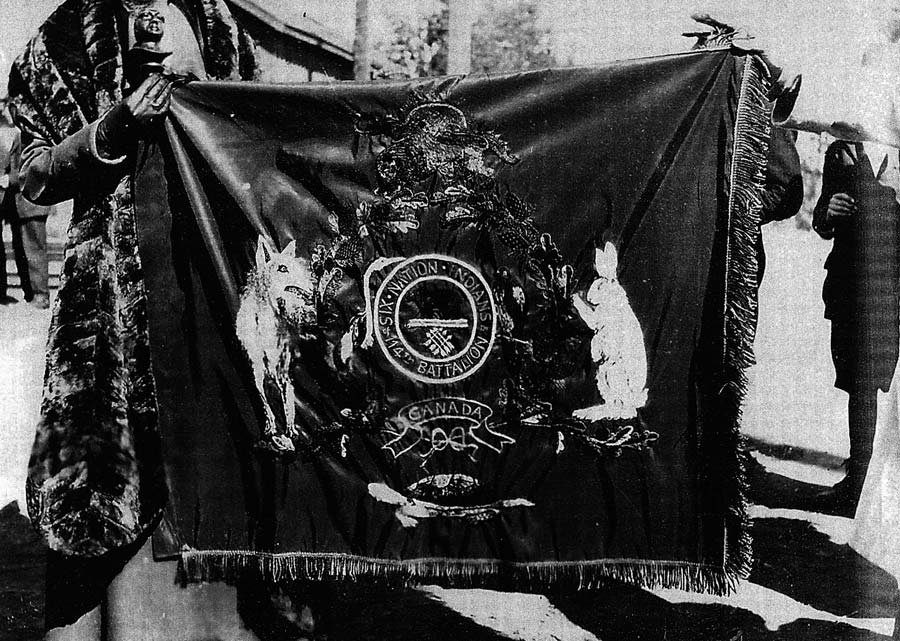

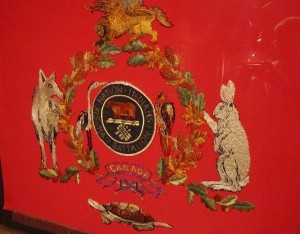

The flag of the 114th Battalion, pictured during World War I with the original flagpole topper. Courtesy Woodland Cultural Centre.

NEWS of Canadian soldiers was almost a daily occurrence in the Scottish newspapers of World War I.

In the midst of that was an account of a tour supporting the 114th Battalion, visiting Edinburgh after a few days in Glasgow.

The Scotsman newspaper on December 11, 1916 reported:

From the highest roof of Edinburgh Castle on Saturday afternoon, four Indian chiefs, head-feathers streaming in the east wind, their bead-covered garments of yellow and red and blue withstanding the rain-laden blast, looked round on the Scottish capital and its environs.

Probably no stranger or more picturesque figures ever stood on the Castle summit. They were members of a company of North American Indians, who visited Edinburgh on Saturday. They and their comrades were cordially hailed by the residents of the Scottish capital, wherever they appeared, as fellow-citizens of the Empire, at whose disposal they have placed their services and their traditional fighting prowess. It was the first occasion on which representatives of the romantic, wandering tribes of the New World have been able in person to associate themselves with the traditions of the Old on the basis of a common militant interest. The presence of the chiefs in their barbaric attire amidst the monuments of ancient feudal life in Scotland presented by the Castle and the Old Town, inevitably stirred the imagination. The contingent numbered over 150. The majority are Iroquois, who are amongst the finest and best-known of the race. They were recruited about a year ago in the Six Nations territory, South Ontario, and in districts near Montreal. The Six Nations forming the Iroquois confederacy are the descendants of the fifty noble families who composed the historic association founded by Hiawatha over four hundred years ago. They are renowned for their astuteness, brain power, and capacity.

The visitors attracted attention as they marched along Princes Street shortly before one o’clock. With the exception of the chiefs, they wore the uniform of the ordinary British soldier. The four chiefs, who carried themselves with all the dignity and distinction of the Red Men of the story books walked abreast at the head of the column. They were Chief Clear Sky, Chief Silversmith, Chief Cook, and Chief Hill. Like their comrades, the chiefs are swarthy skinned and dark-eyeed; and while a native dignity and calmness marked their comportment, they were also full of good-humour, which was manifested in a variety of incidents during their tour of the city.

Clear Sky, their leader, was resplendent in a spreading head-dress of black feathers, white-tipped, leather suit with fringes, an apron of black ornamented with animal figures, with a shawl in rich Indian design and colouring for a shoulder wrap.

His costume was richly ornamented with bead-work, and strings of beads depended [sic] from his neck and head-dress. His conspicuously tall and muscled companion wore a plain suit of brown with very little ornamentation, his head-feathers rising straight up from their circulet foundation. The others were similarly attired. One of them carried a tomahawk, a heavy-headed weapon, which had been used in a battle at Queenston in 1812, the name and date of which being inscribed on the shaft. The projection at the reverse side of the blade had been hollowed out, and formed a pipe, the smoke passage being carried along the centre of the shaft.”1

But Clear Sky wasn’t a hereditary chief – none of the men was. In fact, Clear Sky was a vaudeville performer and researchers have suggested he was presumed to be the main chief as he took the largest head dress with him overseas.2

The story of the 114th is not just about the war that was meant to “end all wars”, but about image and perception, manipulation, and Canada’s historic and ongoing clash between attempted assimilation and asserted independence by indigenous peoples.

A lost history

Many facts remain elusive about the 114th, especially who signed up and where they served once overseas.

But when the centenary of the start of World War I is marked in 2014, it will be a complicated memorial for indigenous communities, not just Six Nations of the Grand River.

Officially prevented from enlisting, then forced to register under conscription, volunteers eventually abandoned upon their return from the front, and ultimately manipulated by the government to suit their own assimilation goals, indigenous peoples still made important contributions to the World War I effort, in money and blood.

Evan Habkirk has become an enthusiastic researcher of the 114th and the complex and largely untold history of Six Nations participation in World War I.

Mr Habkirk admitted he initially had passing knowledge of the Six Nations participation in the war of 1812 beyond a bare minimum on indigenous peoples in Canadian text books on the fur trade and treaty-making in the 1870s.

“I am your average white kid from southwestern Ontario,” said the 30-year-old who wrote his masters dissertation on the 114th3 and is helping search for more information on the men and a lost battalion flagpole topper. “I come from a very small town and knew nothing until my undergrad.”

Mr Habkirk, who is currently working on a PhD at the University of Western Ontario, again on the 114th, said it is difficult to determine specific numbers of Six Nations members who joined the 114th or other groups. Attestation papers in Canada only gave two options: British subject or not. Most would check the British subject box, even if they knew they weren’t, being unable to go and fight otherwise.

The challenge in defining “indigenous” in that period was the exact conflict presented by government upon the return of veterans: each had to choose his identity.

As well as individual choices for enlisting, there were complex political attitudes from the Six Nations Council, the oldest form of government in North America,4 as it tried to stay independent of Canada. That brought them into repeated conflict with the Department of Indian Affairs and others in the Canadian government who were determined to assimilate them.

Six Nations were willing to go to war, to support Britain, but only if Britain asked. Canada could not volunteer or conscript Six Nations and Six Nations could not volunteer to Canada. Just as the Two Row Wampum5 affirmed the relationship of two boats sailing side by side, so the Six Nations continued to assert they were independent and allied to the British crown. They had served alongside the British in the American war of independence, and in the war of 1812, and that was how the alliance was, the council insisted, to continue.

Canada, having bought into concepts of the “glory” of war and local militias, particularly after the Boer War, influenced indigenous communities, and in 1893, the Haldimand Rifles had two companies of Six Nations men, increasing to four by 1904. The 37th had an all Six-Nations brass band. But despite that military tradition, the Six Nations Council and Canadian military both rejected the idea of a Royal Six Nations Regiment in 1896.

It is estimated that at least 10 Six Nations and New Credit men had enlisted by the end of August 1914, including Alfred Styres, a farmer who signed to the 4th Battalion as soon as he heard war had broken out and that nearby Hagersville was recruiting, just as 140 Brantford men offered themselves at the Brantford Armouries in two hours on August 6, 1914. Cameron D Brant, another early volunteer who served with the 37th Haldimand Rifles, was also Brant County’s first war casualty.

But again, in November 1914, a proposal to raise and equip two Six Nations battalions, was rejected because Britain hadn’t asked. If the Six Nations had been asked, chiefs from the council and clan mothers would have appointed “war chiefs” while “peace chiefs” would tend the community at home.

The council did support individuals who went overseas with donations to the Six Nations Patriotic League and even offered $1500 and warriors to Britain, which the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs then rejected. The government said it would have to go to the Canadian Patriotic Fund, which Six Nations in turn rejected because it was “unacceptable to the Six Nations as they did not believe themselves to be part of Canada and therefore wanted the money to be given directly to Britain”.6

In 1917, the council sent a lawyer to buy $150,000 in war bonds – equal to more than $3 million today – but it is unclear what happened to the offer. They did tell the Department of Indian Affairs that they could invest “any and all of Six Nations money into Canada’s Victory War Loan for a period of five years”.7 Again, there is no proof that the department used the money.

The 114th

As more troops were needed, the 114th Battalion, known as the Brock’s Rangers after Sir Isaac Brock at the Battle of Queenston Heights in 1812, recruited about 300 indigenous men and a 30-piece Six Nations brass band. Many of the 300 were from Six Nations of the Grand River, St Regis, Caughnawaga (Kahnawake) and Muncey, and New Credit, Manitoulin Island, Gibson and as far as Manitoba. D Company of the 114th was all Six Nations and the headquarters was based on the Ohsweken Fairgrounds. The Six Nations Patriotic League presented the regimental flag with symbols of Six Nations parallel to those of British crown.

Flag of the 114th Battalion, of the Six Nations, made in 1915 and now kept in the Woodlands Cultural Centre.

In July 1916, the 114th was sent to Camp Borden for more training and shortly after was sent overseas. Disbanding once it reached England, most of its members went to the 36th Battalion or various forestry, construction or railway battalions.

Six Nations support for the war made the relationship with the neighbouring city of Brantford and Brant Council grow steadily stronger through World War I, often at the expense of race relations with Eastern Europeans, explained Mr Habkirk.

But the contributions from Six Nations, in money and men, did not make relations with the government any better once the Military Service Act brought in conscription in May 1917. In January 1918, there was confusion when the Governor General exempted indigenous peoples because they couldn’t vote and were wards of the state. Yet Six Nations men were still told they had to register. All the while the Six Nations Council argued they could not be conscripted and must not register because they were an independent nation and not Canadian citizens.

Even though the Canadian state would not extend Canadian rights such as voting, they insisted on trying to assimilate indigenous peoples as Canadians. And when veterans were later given land under the Soldier Settlement programme, the parcels would be handed out directly from reservation land, supposedly under the control of indigenous councils.

Six Nations might have tried to address concerns to the royal family or Governor General, but their ally Britain largely ignored and eventually pushed them away, with Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston Churchill deferring petitions and other appeals from the community after 1921 to the Canadian government.8

Legislation and political manoeuvring put indigenous people into conflict with the government and themselves. The Indian Act’s marriage clause said Six Nations members were men, while the liquor clause said they were minors. Canada’s first prime minister, John A Macdonald have given indigenous men the vote in Ontario and Quebec in federal elections in 1885, but it was revoked by the Liberals just 11 years later. And section 38 of the Indian Act,9 which is still in place today, was subject to protest from the Six Nations Council as early as 1894 for clashing with their status as British ally.

By 1922, the government had an RCMP detachment set up on Six Nations land in Ohsweken, inflaming tensions. And on October 7, 1924, the Six Nations Council was formally replaced by an elected council as set out in the Indian Act. Despite this, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy has continued.10

Why the 114th matters to history – and the legacy it left for veterans and politics

Six Nations men may have signed up to escape the reservation system, in patriotism after years of militia propaganda from neighbouring communities, or even as an act against the politics of the Six Nations Council itself. Regardless, as a proportion of the community, the men of Six Nations were reported to have given more to World War I than Canada itself.11

Like the rest of Canada, there was a lack of support for families of soldiers while the men were overseas. When Six Nations men returned, they were veterans, but also wards of the state, and Canada then had to decide if they were more veteran or indigenous to determine their benefits.

It wasn’t until 1936, and after public pressure, that indigenous veterans got equal pensions and veterans allowance benefits. In the midst of a fight for money, there was virtually no support for the mental scars left from war.

Mr Habkirk said Six Nations were able to break the colour barrier against non-whites being used for combat troops thanks to their prior military experience.

He said: “That’s why I think the 114th is really important. There were other attempts early on in the war to recruit off of Six Nations because of their noted past military experience and their past military service towards the crown.

“You see similar cases like this with the Maori in New Zealand and other groups that have this noted service to the crown, even though the Six Nations didn’t see their role as ingrained with the crown as much as it was being portrayed in the European newspapers who, at this point, were believing in empire so just bought the thought that Six Nations was following in the steps of their participation to support the empire.”

Most groups or units that set specific recruiting goals in 1915-1916 failed and were eventually split up when they arrived overseas. Though only one company in the 114th was made up entirely of indigenous men, many who volunteered from the Six Nations believed they were supporting a traditional alliance to the crown, not the Canadian state.

“This wasn’t an idea of subjecthood,” insists Mr Habkirk. “This was an idea of being a separate, status-ed ally. That’s where you see conflicting literature all the time, and that’s what makes the first world war controversial for all indigenous groups. You see a lot of them participating and people sometimes look at this participation as their acknowledgement of subject status or loyalty status to the Canadian state, when, in fact, it’s actually them working on their own. And the 114th definitely falls into that.”

“Some [veterans] were told outright lies by the Canadian government about how it was their community was supporting the war, to the point that you do see some Six Nations veterans writing petitions back to the Canadian government saying, ‘Get rid of our current government at the reserve because it’s not supporting us’.

“It was a complete lie that somebody started. It had nothing to do with what was actually happening on the ground at Six Nations. And we see veterans being manipulated when they get home.

“We all know that in Canada that veterans had a hard time integrating back into the Canadian way of life after the war. But what we don’t know is that aboriginal veterans had an entirely new set of circumstances to deal with.

“People were actively trying to manipulate them into falling into certain categories of, ‘are you native or not?’. Decide between your community and your veteran status, and this was almost day one after returning home, where these decisions should NOT be made by veterans who are possibly suffering from shell shock or other problems. These are hard questions for someone who is of sound mind to make, let alone someone who is really just trying to piece together what exactly happened while they were gone.”

On November 11, 1918, World War I ended. But the internal divisions, the conflicts with the Canadian government and the scars of battle would last long after the guns fell silent.

- Further reading on the 114th includes Fred Gaffen’s “Forgotten Soldiers” (Penticton: Theytus Books Ltd, 1985) and Janet Summerby’s “Native Soldiers, Foreign Battlefields” (Ottawa, 1993). Also see Veterans Affairs Canada reference list.

- The Scotsman, “Canadian Indians in Edinburgh: Chief Clear Sky at the Castle”, December 11, 1916, p9. ↩

- Norman, Alison, “Race, Gender and Colonialism: Public Life Among the Six Nations of the Grand River, 1899 – 1939”, PhD Thesis, University of Toronto, 2010. Full copy here. ↩

- Habkirk, Evan, “Militarism, Sovereignty, and Nationalism: Six Nations and the First World War”, Masters thesis, Trent University, 2010. Full copy here. ↩

- About the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. ↩

- Summary on the Two Row Wampum. ↩

- Habkirk, p72. ↩

- Habkirk, p73 ↩

- Habkirk, p101. ↩

- Indian Act 1985, section 38 http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/page-15.html#h-20 ↩

- Mr Habkirk’s work refers to the Six Nations Council and the use of the term in historical records. The formal Haudenosaunee Confederacy remains active under this name. ↩

- Habkirk, p109. This cites the Brantford Expositor of January 22, 1919. ↩