Schools need to teach the value of “sacrifice” as a positive way to promote sustainability and shield young people from “insane” consumerism, an academic has argued.

The idea of “enough” for each person needed to be the basis of guiding the curriculum, particularly in secondary schools, said Leon Robinson, of the school of education at the University of Glasgow.1

And the concept was needed to combat against extremes of not just consumption, but also the extreme minimalism and even radical political positions.

“Got a very bad name, sacrifice,” he said. “Generally people don’t think it’s a good idea. They think of it in terms of giving things up, going without. It doesn’t sound too fun.

“But what I’m suggesting is we need to reclaim the idea of sacrifice to get back to why it was ever seen as a good idea.”

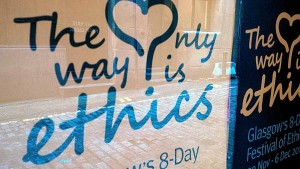

The Only Way is Ethics, an 8-day festival in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2015. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Speaking at the recent “The Only Way Is Ethics” festival2 in the Scottish city, Mr Robinson said both the teachings of Aristotle and the world’s three major religions all emphasised sacrifice and this was a more valuable approach to teaching young people ideas about creating a sustainable planet.

The psychology tradition also teaches “enough”, he said. “Enough is where we should be aiming. That’s absolutely the way we should be aiming. I don’t think it’s taking that approach at the moment.

“I don’t think they have thought it through. I don’t think the concept of sustainability is well enough understood and I don’t think the value of it is realised. There is a preoccupation with growth economics, and that’s not healthy.”

While sustainability is “name checked” throughout the curriculum, in Scotland dubbed the Curriculum for Excellence, and primary schools are doing excellent work, it is not translating to high schools, said Mr Robinson.

He explained to the small audience the Hindu and guru tradition was the opposite of the western world emphasising adding knowledge.

“In the west, education is adding things,” he said. “I need to give you some knowledge, I need to provide you with some skills, I need to give you the means to develop your knowledge and skills. Adding, adding, adding.

“The guru tradition is completely the opposite. What you need to do is get rid of your illusions, get rid of the things that are blocking your true sight, because there is a conviction in hinduism that your true self already has everything it needs. It’s immortal, it’s conscious, it’s joyous.

“All the things that are unnecessary are the things is what the guru will remove: ignorance, suffering, delusion, hatred.

“A diamond in a rough form is a beautiful thing already. But with practical skill, knowledge of what it is that you’re dealing with and how to work with it, you transform what’s already pretty nice into a most extraordinary cut of gem. I’m not saying that necessarily adds value, but it is transformed into something really quite extraordinary. This is a metaphor for how we might look at the value of removing things in order to to reveal the true value.”

In preparing students to become teachers at the university, Mr Robinson said it was vital to consider what images were eventually used to explore issues of sustainability and consumerism in society. Most, even from environmental organisations, were doom and gloom and about the threat to the planet. And while true, he questioned whether that message was working.

Using an image of drunk young people in a Glasgow park, he suspected that was a “flight from some sort of unhappiness”.

He told the audience: “We do have a consumer culture which is almost overwhelming, that people swim through it like fish through water. They don’t even question it. People assume that money is real.

“It’s an insane game run by the privileged. But it’s a game that we’ve been born into. It’s a game that we assume is reality. Of course it’s not reality – we could change the rules tomorrow. The problem is, people who are born into this culture, really do love it.”

[Tweet “”We have a consumer culture … people swim through it like fish through water.””]Instead, Mr Robinson said there needed to be an appreciation for the concepts of “satisfaction” and “contentment”, pointing out the root Latin words.

“Satis is latin for enough,” he said. “Satisfaction is the making of enough. Contentment, the content of what you have in you – happiness with what you have, not craving more, not craving excess, not needing to change by adding – just being content.”

Tomorrow asked the Scottish Secondary Teachers’ Association for comment on how sustainability is taught in schools but they said they were unable to comment.

The Curriculum for Excellence allows teachers to develop their own approaches in the classroom, aimed at particular “outcomes” from ages three to 18. “Sustainable” or “sustainability” are mentioned 17 times in the Curriculum For Excellence 317-page “outcomes” document. “Enterprise” or “enterprising” are used 22 times. “Sacrifice” appears only once, under the section for “Catholic Christianity”. “Enough” is not used at all.3

- Leon Robinson profile page. ↩

- Festival website. ↩

- CfE “outcomes” document from Education Scotland website. ↩