Shipping containers in Camp Bastion in Afghanistan, ahead of the draw down by British forces in 2014. Photo taken by Liz Perkins in August 2014. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

ON August 26, 1954, a patent was filed at the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Malcolm P McLean of Winston-Salem, North Carolina.1

Sixty years later, the modern shipping container is everywhere and is responsible for much of the clothing on our backs, the shoes on our feet, the umbrellas over our heads, the furniture in our homes and the digital devices on which you are currently reading this.

“My present invention relates to water-borne freight movements and more particularly to a means for stowing cargo aboard an otherwise single purpose vessel whereby the pay load of such vessels may be greatly augmented without materially detracting from the primary load carrying capabilities of the vessel,” opens the application.

“Cargo” has included most recently 35 Afghan Sikhs, including children and one man who died, were found in a shipping container in the British port of Tilbury2. “Intermodalism” has changed lives as well as the world.

Containers, defined as 20-foot equivalent unit (or TEU), are mostly 2 TEU, or 40 feet in length (also called FEU). Drewry Maritime Research, which sells data on containers and their contents, said that there were 32.9 million TEU during 2012. The World Shipping Council said 120 million container loads of cargo were transported in 2013.

That’s a long way from the 58 aluminium boxes loaded on to a ship in Newark, New Jersey on April 26, 1956, bound for Houston, Texas. The Ideal-X is credited as the birth of the shipping container, but it took decades to gain the agreements and standardisation across industry and government to make them as dominant as they are 60 years on.

Mr McLean’s efforts became SeaLand Services, followed later by Matson Navigation Company and many others. Not all containers arrive at their destination, with disputes over just how many may be lost at sea, ranging from 350 a year to 10,000. Those can pose significant risks for smaller vessels, many floating just below the surface, but also for the environment, dumping goods on beaches around the globe.

To mark 60 years since the original patent was filed, Tomorrow collected seven voices with very different perspectives on shipping containers and how they have changed the world, and individual lives.

The longshoreman

Gene Vrana, 71, was born in New York City and moved west to start working on the waterfront in San Francisco in 1968. He registered on the longshore workforce in 1969 as a member of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU)3 and became their education director after getting an injury on the docks in 1984. He retired in 2010.

“I knew that I wanted to work in the waterfront. I had been drawn to work on or near the sea but also I was drawn to the traditions of the union on the waterfront.

When I was a kid, my father would talk to me occasionally about how being a merchant seaman or working on the docks was an honourable occupation with a militant, proud history. And being around New York City and New England a bit, I just had that sense of the sea and then I started reading and I was drawn to Jack London and, I don’t know, Moby Dick? It’s a combination of life experience and literature growing up that I was predisposed to be working out of doors at a hard, physical occupation that was connected with a certain political legacy that was still dynamic. And I wanted to be part of that.

There was a quick learning curve required because of the hazards on the job. But in terms of how the men – and at that time it was all men – related to each other on the job and how they talked about their lives and their feelings about the union were things that fit.

The first jobs I had in 1968 were as a casual worker – I was in the warehouse division at the ILWU and if there were extra longshore jobs on a given day and you were sitting in the warehouse division hiring hall, you had a shot at those.

I picked up a few of those in ’68 and they were mainly in the East Bay and containerisation was mainly at SeaLand and Matson Navigation – Madison was starting to refit their sugar ships to and from Hawaii to accommodate containers. And SeaLand, which was born on the east coast, was just beginning to take off.

It was Vietnam that pushed it – within two years there was much more construction or reconfiguration of the ports of Oakland and San Francisco to accommodate what, at that time, were mainly 20ft containers.

In many places they were still small enough to use existing docks. But then the terminals, especially in Oakland, which had the acreage, just began to take over and replace the terminals where break bulk or general cargo had been handled. By the end of the Vietnam War – we’re talking essentially about a five-year period – the technology was there and it was changing work rapidly.

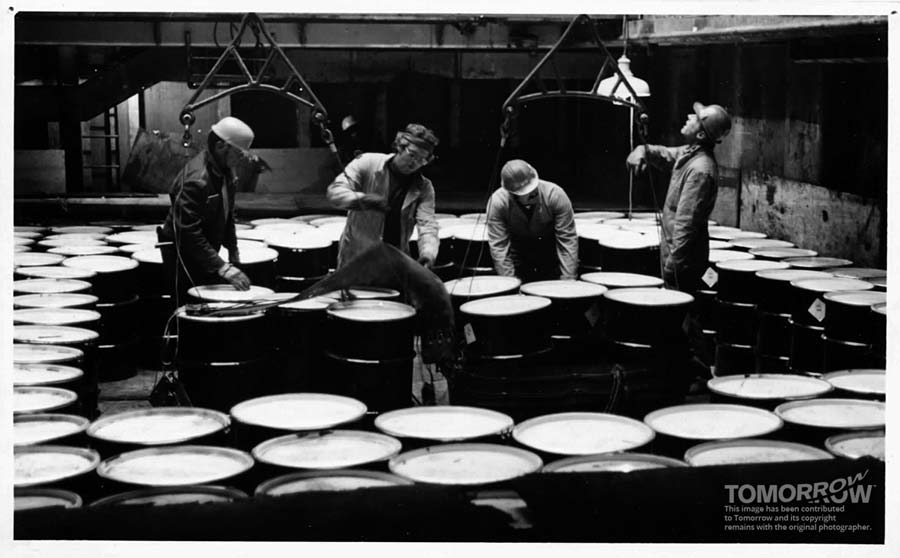

Those guys with the lowest seniority by the mid ’70s were getting the lashing jobs on board the container ships, working the new technology on the deck and on the shore to secure or unsecure the containers with lashings and all that. And that took the place of what had been the grunt work of throwing cargo sacks or boxes of apples or whatever.

My generation, the guys that came in in the mid to late ’60s, just saw it change right before our eyes. Not only was the technology changing but the relationships on the job changed because you were no longer working in a gang of eight to 12 guys. You were working maybe two together, or even solitary, dealing with different aspects of either machinery or gear associated with machinery for moving the containers on and off the ship.

With the change in the social aspect, along with the technology, it just felt that the work experience within any day was just not the same.

I worked in a gang that only worked the old general break, bulk cargo up until ’82. Those of us that were in a gang and working with 12 other guys and talking politics and talking family and whatever, had a very different work life than guys who were driving cranes or other container moving technology where they were isolated during the work shift.

A more unpredictable schedule was more common with the container ships. The ships would come in and turn around – and we’re talking now about the ’70s and ’80s – in between 32 and 36 hours, max. The overtime shift occurs on the last shift in order to finish working the ship, getting it ready to sail.

So if they’re sailing with more frequency, the frequency of working late is greater. That kind of thing had more of an effect than on the old fashioned ship that would be in port for 7-8 days and you would go to the same ship and even the same hold of the ship day after day working from 8 ’til 5.

We were the younger guys until the early ’80s when they started bringing some new men and women into the industry. Not only had we been through the 1971 strike, which was the first major strike after 1948, but we also had been involved in the union and the workplace where the steward system, where many of the active union members were. Those who came on board in the late ’70s and [early] ’80s didn’t experience any of that and they were presented with conditions and benefits and wages that were far beyond what any of them had experienced before. They didn’t have any personal connection, because the oldtimers had retired. That’s how they were getting hired, was to replace those that were being retired.

There was a shift in the generations that happened to be concurrent with the technological change, but is also a loss of generations and generational memory that had a lot to do with the change.

I would that say I maintained my pride, partly, working in a gang until the early ’80s, because I wanted to stay working in that older kind of environment, the more socialised environment. That was conscious.

But the other part too was being active in the union. So that later on, when I got injured on the job and I couldn’t continue working on the waterfront, I went back to school and I got a graduate degree in archives management and then I went to work for the international headquarters of the union, running the archive and research library.

Then I became the education director, which was mainly leadership development programmes for the last 15 years that I was there. Part of my intent – and this was with the encouragement and blessing of the officers of the union – was that we had to develop an education programme to overcome the gaps of new people who were not part of the struggle and were no longer coming from families that were steeped in the struggle. There was no longer a passing along from generation to generation of the occupation of being a longshoreman; because of legal reasons in order to achieve diversity on the waterfront, depending on what port you’re talking about, whether it’s by gender or by race, that had to randomise the selection process.

You no longer had from father to son to brother to nephew to son or that kind of chain, which had been the case for several decades. Trying to meet that challenge was what we tried to address in the education process, which I personally found to be really meaningful, to try and find ways to recapture and replicate the values and understanding of the attitudes of the generation that had built the union, so that a new generation, who were stepping up into leadership but often without a compass – a political compass, definitely they had a moral compass – but an organisation sense of how do we achieve this in a democratic but yet militant fashion.

I don’t think that there is a deep or concrete sense of connection to how product is created and distributed and the people connected with it. The idea of identifying and preserving the history of the people who did that kind of work on the ship or on the dock was, to me, something that become a sense of a mission.

But I think the connection between who does the work and what kind of work it is that moves those goods is something which is not well understood. There have been some efforts, like the Smithsonian and in some of the Pacific coast maritime museums, to show the kind of work that it takes to operate the crane technology or the intermodal technology to move the container and to get the goods into the container and out of it.

The technology is NOT, in and of itself, an evil thing. There’s a whole strain in the history of the ILWU with coming to terms with containerisation. You had Harry Bridges and those that were in support of him who viewed much of longshore work as being dangerous and backbreaking. And he felt not to romanticise it and that mechanisation, if done properly, could lighten the load on the individual worker and prolong their life and health by doing that.

I don’t know if he could have envisioned what we’re seeing now, which is robotic terminals. But now the issue becomes the longshore workforce doing as much with moving information about the freight as it is moving the freight itself. And are we going to gain jurisdiction over computer maintenance and repair and innovation and implementation of even newer technologies? Or are we just going to be cut away, cut away, cut away, because they don’t need human beings anymore? At least not human beings that come out of the union hall. That’s part of the struggle that’s going on right now.

I’m going on here – for some reason you pushed my buttons.

There’s no such thing as unskilled labour. At any point in the movement of goods, from one place to another, from manufacturer to distribution, from one mode of transport to another, involves a lot of experience and a lot of knowledge for it to be done safely and properly. And it doesn’t matter at what point in the timeline of technological change you point your finger, but at that point, it took a lot of skill to achieve that movement and distribution.

Think about that. Because I think one of the things when people think about whether it’s truckers or dock workers is they think that they’re overpaid and doing something that anybody with any IQ could do.

As long as cargo moves from waterborne ships or devices-not-yet-built to land, longshore workers are going to be essential to do that and their importance to the national and international economy should be understood and respected.

Longshore workers benefit from all forms of international commerce. While we don’t see the product being made here, because so much of it is being produced overseas, everything that goes into the container is made by someone somewhere for somebody’s benefit.

And at some point we need to ask what are the conditions under which people are creating the product, and what’s the consequence of having it produced somewhere else other than the United States, or without the kind of labour standards that are deserved by anybody anywhere who makes those things.”

Vietnam, capitalist utopia and The Wire

Dr Alex Colas is a senior lecturer in international relations at Birkbeck College (University of London)4 and co-hosted “The Ship of Empty Boxes” conference in January5 Amongst the participants was the Delta Arts group connected with co-host Dr Sophie Hope. The event examined imperialism, globalisation, the “social life of things” and the aesthetics of not just shipping containers but the sea on which they travel, and within which they are sometimes lost. The film The Forgotten Space was also shown.

“The hidden space is more about the sea itself and the forgotten space is the space of the maritime.

I think it works with reference to containers as something that seems to be taken for granted because it’s just a vehicle, a freight technology that carries stuff. I guess people like the director of the film, The Forgotten Space, and many of us that come from more radical perspectives, want to emphasise that that is just an appearance. Because actually, in the content of those very boxes, are a set of unequal social and international relations between workers and corporations, between the actual seamen that work within the container ships and the captains. And if you prise open the box, try to check its biography, all sorts of unequal social relations come up.

Shipping containers are used for storage for Wakedock, Ireland’s first cable wakeboard park at Dublin’s Grand Canal Dock. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

In a way, that’s a device for thinking through what appears to be a purely neutral and universal exchange – this is just a box that carries stuff – actually then opens up all kinds of other, more complex, social relations. That’s the starting point.

At one level, there’s a very banal and superficial narrative – ok, there’s a technology that we take for granted because it simply met the increasing need for people to trade in goods. Nations like to trade and therefore you invent a technology that facilitates that.

But actually I think it was a much more complicated story. It’s less about the market and less about competition, and it’s much more about water and logistics with relation to Vietnam. It’s much more about banging heads together amongst industry, regulators, amongst politicians, in the US in particular. It’s about international cooperation in creating a standard that eventually became the 20-equivalent unit.

My take on these things is that far from being a result of a natural tendency to truck and barter, actually the container is a consequence – I’m not saying it’s some tidy story – of various political manoeuvres to facilitate trade.

It’s both a box and much more than a box. It just encapsulates a series of political decisions as to how the world should be organised economically and the key was it’s the flattening of space, basically, to put it somewhat abstractly.

The fact that it was SeaLand is telling – the idea you flatten any geographical or physical material realities and you just create a smooth space that can transition from anywhere, from land to sea, but also from anywhere in China to anywhere in the US and anywhere in between.

It’s a smooth vehicle of universal exchange. And that literally is a capitalist utopia. That’s really what an ideal of capitalist markets should be, one where there’s absolutely no interruption to the flow – there’s a constant circulation.

I think this is where is gets difficult because I wouldn’t want to say for a minute that it is exclusively causal – it’s not the reason why there’s globalisation. In many respects the box is a product of globalisation. It’s both a cause and a consequence.

Shipping containers in Camp Bastion in Afghanistan, ahead of the draw down by British forces in 2014. Photo taken by Liz Perkins in August 2014. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

And I think very clearly in certain junctions, like for example in the Vietnam War, the container plays an important role in facilitating US presence in South East Asia. Now, obviously, US presence in South East Asia isn’t there because of the container, literally. But at a certain juncture the US army and navy had a serious problem of logistics because they simply couldn’t deliver the amount of material that they needed, be it military or support of their military operation there. And then the container becomes a way of solving that.

The primary reason for being there is much more geopolitical, but this particular freight technology facilitates that. In certain contexts like that, the box participates in a world order. You don’t need a war for the container to operate. As we know, about 90 per cent of trade is through the container and in some respects it is a very pacific, non-aggressive technology. It just conveys things from one part of the world to the other.

That’s just a superficial manifestation of the box. Underlying it are all kinds of other much more unsavoury, exploitative, oppressive kinds of relations. The guys who create our mobile phones in factories in China, they are part of the box; and we are related to them in one way or another through the box as well. If suddenly you abolished containerisation, let’s imagine, that kind of exploitation would not disappear. But it certainly would be different.

The second series of The Wire tells a story about all kinds of violences: gender violence, racial segregation, political antagonism, class struggle and whatnot. All those kinds of social relations I think the container acts as a vector for that. Arguably you could do that with all kinds of other things. But in this case it just happens to be a container.

In Shoreditch, UK, they’ve got a small shopping mall made up of containers and there are containers as Pizza Huts in Helmand province in southern Afghanistan. This is a perfect metaphor, literally, as in the carrier of capitalism, because it’s something very universal. Everybody can recognise what it is, each port across the world will have an equivalent 20 TEU. And yet, it is deeply specific or it can be used for specific purposes and that tells us a lot about capitalism.

People often think, ‘Oh this is just a box for Christ’s sake. What else is it? It’s just a mechanism for making certain goods cheaper’.

But actually, if you follow the social history of this thing, then there is much more in it.”

The beachcomber

Tracey Williams, writer, beachcomber and creator of the Lego Lost At Sea Facebook page,6 stemming from items collected on the beaches of South Devon and Newquay washed ashore from one of many containers that fell from the Tokio Express in 1997.

Items collected on English beaches, washed ashore from shipping containers lost from the Tokio Express. Photo by Tracey Williams / Lego Lost At Sea.

“We’ve been picking up toothbrushes, lighters, cigarettes, tiny plastic toy wheels and intravenous drip bags – all from cargo spills.

A great deal of debris ended up on our shores when the containers fell off the Tokio Express. The coastguard reported at the time that there were 100,000 lighters littering Cornish beaches. Quantities of methyl methacrylate monomer, inhibited – a hazardous substance – also reached the shoreline.

We still don’t know what was in all the other 60+ containers that fell off the Tokio Express, though wheelbarrow wheels were said to have been in one. Many people were thrilled to find the Lego though – and still are.

Back in the late 1990s I used to spend many happy hours beachcombing with my children. We used to have treasure hunts – we picked up hundreds if not thousands of tiny flippers, spear guns and scuba tanks. The holy grail was always the Lego dragon or octopus. It wasn’t until years later that I found out quite how much Lego had been spilled and the impact it had had on the environment. We still find it virtually every day.

At the time I wasn’t aware how many containers fell into the ocean every year. It’s only in recent years I have discovered the scale of the problem. The state of some of our beaches is shocking. It’s not just container spills though – we pick up huge amounts of fishing debris and global garbage thought to have been dumped by ships.

One of the biggest problems on the beach are nurdles or mermaids tears – the tiny pre-production microplastic pellets. Billions wash up. I picked up more than 10,000 of these from one tiny rock pool one day – a rock pool that had once been teeming with wildlife. Many of these nurdles are thought to come from cargo spills. They threaten marine life and can choke small creatures. They can also act as sponges and carry micro pollutants and have been found in the digestive tracts of marine creatures.”

Before and after photos of a rock pool showing the damage from plastic nurdles washing ashore with the tide. Photo by Tracey Williams / Lego Lost At Sea.

Items collected on English beaches, washed ashore from shipping containers lost from the Tokio Express. Nurdles, the plastic bits left from the manufacturing process, are common items found. Photo by Tracey Williams / Lego Lost At Sea.

Items collected on English beaches, washed ashore from shipping containers lost from the Tokio Express. Nurdles, the plastic bits left from the manufacturing process, are common items found. Photo by Tracey Williams / Lego Lost At Sea.

The changes to the port, and us

Saskia Sassen is a Dutch-American sociologist focusing in globalisation, global cities and international human migration.7 She is currently the Robert S Lynd professor of sociology and co-chairs the committee on global thought at Columbia University.

***

“Containerisation enhances consumption. You can move anything from anywhere to your city. But in the space of the port—which may or may not be near a city, such as Hamburg or Rotterdam – it has brought in a whole new industrial and logistic function to cities, unloading those huge containers form ships, storing them, and then distributing the goods. But it is done with fewer workers. Ports used to be far more labor intensive. Now they are extremely machine-intensive.

Shipping containers are used for storage for Wakedock, Ireland’s first cable wakeboard park at Dublin’s Grand Canal Dock. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Containerisation and the ease of transport have generated a sense that we can get X no matter where we have to get it from. This is clearly not good. The worst part is that once you have these huge costly systems in place it is difficult to change. We are very much, in many different ways, captives of the advances in transport engineering and computerised logistics that constitute forms of knowledge we admire.

It has changed how we think about ‘stuff’. It started by astonishment: ‘We can get it from anywhere in the world?!’ And now it has degenerated into expectation: ‘Well of course we can get it from anywhere in the world’.

I can’t help but think of this wonderful artist from Spain who did a three-year project on containers. And then I remember in a show in New York where I was asked to be a co-curator, one of the artists we brought over from Japan had done this amazing installation in a container. And he insisted that the container had to be brought from Japan. And we did, because it was a way of accentuating and telling another story about this massive apparatus being transported. And then it was in the show – and it was spectacular. Now that I think about it, I have had more intersections with containers than I realised.”

The restaurant

Ska Brewing Co in Durango, Colorado opened The Container Restaurant8 in August 2013. The space opens on to their tasting room and is easily warm enough in winter from the pizza oven in the container downstairs acting as a kitchen. Marketing manager Kristen Muraro describes the idea from co-owner Matt Vincent and how the community has taken to it.

The Container Restaurant, Ska Brewing Co, Durango, Colorado. Contributed photo. Copyright remains with the original photographer.

“Originally we had a local Mexican food restaurant in an Airstream trailer parked out in our beer garden.

We were more focused on the tasting room and the beer side of things and we’re not a restaurant or a brew pub. It was self-sufficient and self-sustaining. And then they moved on so we lost that food option.

The Container Restaurant, Ska Brewing Co, Durango, Colorado. Contributed photo. Copyright remains with the original photographer.

We’re very limited on space here and one of our three owners, who is kind of the mastermind behind our design and our building and the plant engineer, has always wanted to make something with shipping containers. It’s just something he’s seen for years and years and thought that they’re very versatile and he liked the idea of repurposing something, which we do a lot of here.

We have a lot of sustainable focus on our building itself. We use blue jeans as insulation in the walls and in our tasting room the tables are made out of recycled bowling alley lanes and the bar is as well. So they brought green, sustainable building practices here – the shipping containers worked in perfectly.

We had to get creative on a lot of things. Trying to fit everything in there and making sure everything’s up to code, sprinklers and everything else that has to go into a kitchen, it was definitely creative but they made it work. The top one is longer than the bottom – we had to cut about a 10ft section off to fit the space we needed to put it in, but then we used that 10ft section as our walk-in freezer.

I think they enjoyed creating the space and doing it.

This particular space and what they’ve done when they built the building and some different things that we’ve tried, it just kind of fit in with the overall thinking outside of the box, so to speak, approach to being creative.

The Container Restaurant, Ska Brewing Co, Durango, Colorado. Contributed photo. Copyright remains with the original photographer.

Matt has looked at containers as useful for years. He’s looked beyond what the normal person would think of a shipping container and he’s educated all of us to that. And we’ve seen all these other cities and towns worldwide where there’s apartment buildings, communities built out of them, and seen how nice they can look and how much can be done with them.

Now people in this area are seeing what can be done with them too. We’re far from any place else. Denver 6.5 hours away is probably the closest place where people have used shipping containers for other uses so it’s not something you see every day down here.

I don’t think there’s any other shipping container here in the Four Corners [area] or in Durango. I’ve had people come in and say, ‘Oh, I can put one of those on my property and turn it into a little studio apartment’. The public have come in and seen what can be done with it and I think we’ve educated them on the usefulness of repurposing what some people might consider ugly boxes.”

The Container Restaurant, Ska Brewing Co, Durango, Colorado. Contributed photo. Copyright remains with the original photographer.

The music video director

Filmmaker Noble Jones9 has worked with Taylor Swift, Mary J Blige, Seal, Michael Bublé and Natalie Cole and was the second unit director for The Social Network. In 2010 he directed the music video for the song “Ain’t Nothing Wrong With That” by Robert Randolph and The Family Band.

“I got the idea for the video from listening to the lyrics and thinking of an interesting way to make social commentary tied to a strong visual signature. The interior of a shipping container looks like a backlit corridor, always a cool image. Many sci fi and mystery movies have proven its effectiveness countless times.

The idea of America shipping its culture all over the world was the subtext/text of the idea (Music Videos don’t often allow for subtlety) so naturally showing them ‘shipped off’ at the end was the obvious conclusion to the video. Couple that with the singer saying, ‘Let it go!’ over and over again, like a funky foreman at a dockyard and there it is.

The sense of scope and impact, the spectacle of it all is something any filmmaker often wishes to achieve if budgets allow. In this case, I think we got a smart video with a bit of spectacle for much less than one might expect.

The only challenge using them was time. Moving them around required a day in itself. The actual filming was easy because I could suggest the inside of one container is any container in the block we created.

The shipping container is iconic, finding it’s way into the popular culture because of its versatility. It suggests a one-size-fits-all approach to our modern world that can be both liberating and constricting. I suppose that what creativity is all about.”

The stunt double

Peter Kent, 57, is a former stunt man for Arnold Schwarzenegger and now runs Peter Kent’s School of Hard Knocks,10 teaching future generations of stunt doubles.

In 1996 on the set of Eraser, staring Schwarzenegger and Vanessa Williams, he was nearly killed filming some of the final scenes involving a three-tonne shipping container.

Stuntman Peter Kent pictured in a scene in the film Eraser in 1996. The following scene in the movie involved a stunt that nearly killed Mr Kent and two others.

“The box was 100ft in the air on a gantry crane, the box itself, and Arnold’s character is supposed to smash the gear and the box is supposed to drop with us on top of us it.

Somebody – it wasn’t us, the stunt guys were never even consulted really on it – just said, ‘I think the stunt guys can do this’.

Initially we would fall 90ft or whatever with the box and then the wire on our backs would pull us off and it would look from above with the camera like we rode it right to the ground.

They had cable cutters on each corner of the box, which were designed, supposedly, to fire all simultaneously, thus making the box drop level and flat. And these were apparently the same cutters that they used on the space shuttle.

We had a bad gut feeling about it – all the stunt guys and the girl as well. You can’t call a $100,000 gag on a bad feeling, or you never work again. But of course you never work again if you’re killed either.

We were watching the effects guys and they said, ‘Go away, don’t bother us right now, we’ve got a lot on our plate here to deal with’ and we’re all watching them do it.

So we got up there and I was expecting to see the box fall beneath my feet flat and then feel the wire jerk.

And all of a sudden the next thing I felt was CRACK across my back and I was going toward the wall of the warehouse about 65-70ft away. And I reached the end of my wire and it all of a sudden yanked and spun me around. I looked back and there was the box now spinning by one cable.

What had happened was they wired it in series instead of parallel. Instead of one-two-one-two, they wired it one-two-three-four. And so it went bang-bang-bang-click because there wasn’t enough voltage to fire the last one.

And so it was spinning and it wrapped my wire up in it because I had the longest wire.

The guy who was doubling James Caan just kind of slid down the box and was out of the way, and the girl who was doubling Vanessa Williams was actually cabled off to the gantry part of the rig up high and so I took the beating. It just wound my wire in and it just kept hitting me and hitting me until basically the inertia of it hitting me was gone.

I broke collar bone, scapula, top three ribs and that was it – came to rest sort of underneath the box, and at that point had that cable [on the box] finally cut it would have just driven me right into the ground.

At that point everybody was screaming and freaking out. I remember hearing some of that because I was kind of dazed. And they came in a cherry picker with wire cutters and cut my cable lose so I could crawl into the cherry picker.

I looked up and April [Weeden] – who was the girl doubling Vanessa Williams – was hanging upside down and I thought she was dead. And I said, ‘Get up there – let’s get her right away’ and we got up there and she was unconscious. I thought she was dead for sure. I was shaking and saying ‘April April’ and she woke up screaming. And I cut her cable and as soon as she fell into the cherry picker I blacked out.

My recovery was about a couple of months.

On Last Action Hero I did all kinds of stuff – I did an accelerator down the side of a 20-storey hotel, did crane work at least 30 storeys in the air hanging off of a crane. I did a couple of high falls from some 10-15 storeys up, which was pretty much the height you used to go in those days. The concern [on Eraser] was more that there was a three-tonne box involved, which basically I got married to by virtue of my cable tangling up in it, and then it just beat on me.

I did stunts for 15 years and I’m the longest running double in Hollywood basically for one actor and I’m in the Hollywood Stuntman’s Hall of Fame because of it. But what kept me alive all those years was just paying attention to what was going on and not sitting in my trailer.

On Eraser we all knew something bad was going to happen, we just all felt it. I’ve always been one to come out of my trailer and if they say this is the gag, if I can see it first, great. If it’s an explosion I’ve got to be involved in it – I want to see how that’s going to work. Don’t just put me in place and then set it off. I think that a lot of that is contributed to my longevity. Literally. Just being proactive with your own safety, and I teach that, I expand that quite a lot for my students.

Did anyone learn anything from that stunt? I don’t think so. It’s a typical Hollywood thing where everyone’s told to hurry up and get moving and get it down and under pressure, a lot of safety stuff gets ignored. What I found was a little ridiculous was that the effects guys – the accident was basically 100 per cent their fault – and nobody even ever apologised for it. Nobody even had the guts to say, ‘Shit, you almost died – sorry about that’.”

And would Mr Kent recommend stunt doubles avoid working with shipping containers?

“Watch your ass is what they say. Check it out and if it is wired in series, then don’t do the gag.

There was nothing they could use of our shot because it went sideways instantly. We were all in the hospital and there was no way to go back and do any of it – and none of us would have gotten back up there again anyway. So they had to use the CGI version of it. It looks ok. Some of the CG in that movie was a little bit weak, like the alligators – I found the alligators were a little bit sloppy.

Basically it was the end of my career. I just looked at that and said, ‘You know what? This is basically god’s unsubtle tap on the shoulder that it’s time to go’.

And I realised at that point that I had been doing it a long time – 15 years – and I think it’s time to get out of here while I still can. So that’s what I did. I just quit at that point and I moved back to Vancouver and started up my school and all that.

In retrospect it was a good thing – it’s probably what needed to happen. And now I’ve got my two five-year-old twin boys running around here like maniacs. And they both try to do all the same shit daddy does.

One of them’s a bicycle fanatic and the other one’s already split his mouth open and gotten a bunch of stitches in his lip from falling out of the tree fort. They’re hot on my heels, much to my wife’s concern.

Guys, calm down, stop jumping on the furniture. Daddy’s on the phone.”

Have you had an experience with shipping containers? How have they changed your life, your business, your world? Please share and engage.

- Full USPTO patent. ↩

- Two people have since been arrested since the discovery. ↩

- www.ilwu.org ↩

- Dr Alex Colas ↩

- The Ship of Empty Boxes. ↩

- www.facebook.com/legolostatsea ↩

- http://www.saskiasassen.com/ ↩

- http://containerrestaurant.com/ ↩

- http://noble-jones.net/ ↩

- School of Hard Knocks. ↩