The Evergreen Forest, as remembered 30 years on by the artists who drew the trees

This is story of The Raccoons: unique, successful, Canadian. That is, until television changed.

Life would be simple in animated forests except for, technology. And tech might be overwhelming for the industry except everyone still remembers the creativity of The Raccoons.

The television show, following three specials, premiered in 1985 and was given prime time space on Canadian screens and picked up around the globe.

When it first debuted, the half-hour programme was so popular it pulled in three quarters of Canadian eyeballs aged two to 11 – a market share that would make advertisers giddy today.

But putting together a show didn’t just involve animators. Storyboard artists, background artists, inbetweeners, opaquers, matchers, layout artists, colour checkers, final checkers, xerographers, as well as sound and music staff and those providing voices to the characters and others were all vital. And it was all under one roof, to this day one of the only such set ups alumni experienced – and appreciated.

“It’s wonderful how The Raccoons, its fingers of delight, have stretched out into so many communities,” Kate Wallis, an assistant on the production, says looking back.

“How wonderful it is to have that Canadian cultural touchstone, like Littlest Hobo or Beachcombers. Raccoons is right up there with Canadian classics.”

Tomorrow looks back three decades to the start of The Raccoons, how it changed lives and how animation has changed even as the passion remains.

“Run with us”

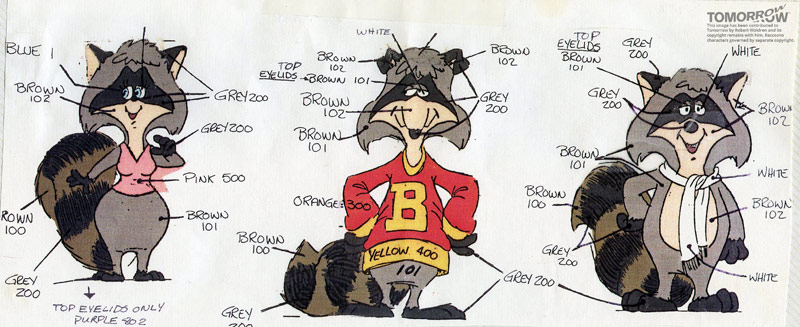

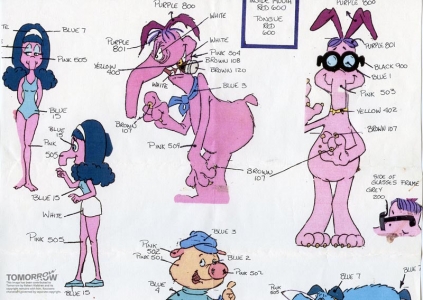

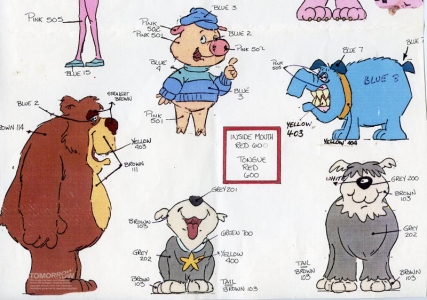

The Raccoons,1 created by Kevin Gillis, was a first job for many straight out of Sheridan College in Toronto, Ontario,2 or after a drought of unemployment in the early 1980s. Car loads of graduates drove to Ottawa in 1984 for interviews for a new production.

Most started out assisting or “inbetweening” – if an animator would do drawings one and five in a sequence, then an assistant would do drawing three and the inbetweener two and four. The more images in a sequence, the more straight forward it is, and you can get promoted as you learn, explain alumni of the show.

Gerard de Souza,3 a self-professed “animation nerd” remembers at the age of six declaring he wanted to be an “animated cartoonist”. By junior high, his dream had evolved to “cartoonist”, living just down the road from Sheridan College.

Armed with the naivety that life would be “9 to 5” based on the example of his parents, Mr de Souza discovered the animation course at Sheridan – they didn’t have one for cartoonist. After graduating in 1984, aged 23, he was one of the many heading to Ottawa to work for Atkinson Film-Arts.

Robert Waldren4 graduated from Sheridan College in 1983 and the next summer got recruited to start work in October, a year before the show eventually premiered in Canada.

Nik Ranieri5 also headed up to an interview with fellow Sheridan graduates, and remembers a bumpy start.

“My first job on The Raccoons was actually in layout and that lasted about a week,” laughs Mr Ranieri by phone from California. “I did one layout and they were like, ‘Okay this isn’t going to work’ and I’m like, ‘Good because I didn’t enjoy this at all and I’m not really a layout artist’.

“So they put me in inbetweening and assisting first. I was right out of college so I don’t think they really thought of me as an animator at that time. But of course I really, really, really wanted to animate, so I would do everything I could just to work my way up.”

Mr Ranieri only worked on the first seven of 11 episodes in the first series before he moved on, but still remembers the living quarters – in the same building as the second floor studios, the Colonel By Towers.6

“A lot of my memories of Raccoons were just, it was freezing in Ottawa, and waiting for buses, and the fights for higher wages.

“And even within all that I still managed to save a good sizeable amount of money so I was able to travel to England to get that first job on [Who Framed] Roger Rabbit because actually I pretty much lived at that studio – and I mean literally lived at the studio.

“Some people, you never left that building for weeks – they’d sleep, they’d come back down in the morning and go to work. It was such a bizarre situation having an animation studio in a residence.”

Colonel By Towers from Bronson Avenue in Ottawa. Many staff lived in the floors above the studios.

Colonel By Towers, with a Scotiabank on the ground floor, The Raccoons studios on the second floor, paper covering the windows to be able to better see the art.

On the ground floor was a Scotiabank branch and, while cashing his pay late one Friday as the bank was closing, Tim Deacon7 was confronted by two robbers.

“I turned in the line to stare down a revolver barrel,” he says by email. “The follies of youth sometimes make you feel invincible but I kept my cool and studied his features. Seeming unnerved he motioned everyone into the walk-in safe and both quickly left with the alarm blaring. I quickly began sketching up both men and went police to station to identify them later.”

But amongst more fond memories was the ball hockey rivalry between the animators and the background artists.

“This went on for many years in the form of cage match tournaments for the coveted ‘Raccoon Cup’ trophy and bragging rights,” adds Mr Deacon, who was a layout artist designing and drawing in pencil scene locations and camera moves. “All the artists were a close-knit group sharing as much fun time outside the studio as possible.”

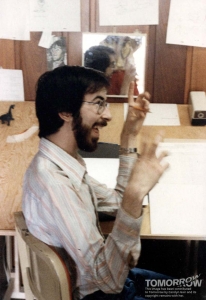

Most Canadian photo ever? The ball hockey players who animated The Raccoons.

Carolyn Gair8 was another Sheridan graduate and had risen from being an assistant on Care Bears specials before starting at The Raccoons.

“Being a junior animator on The Raccoons,” recounts Ms Gair by email from California, “I remember thinking that I’d wished we had more animation training at Sheridan.

“The three-year course that I enrolled in 1979 taught students how to make an entire film, from story concept to animation and layout, to cell painting, filming, sound mixing and editorial.

“When we graduated in 1983, it was into a world where there was an animation job drought. Many of my classmates took what expertise they learned during the filmmaking process and took jobs in other departments, camera, sound, editorial, layout, background, special effects, as there just were no jobs in animation itself.

“Also, we were largely unprepared to join the job market as, yes, we could make an entire film from start to finish, but we had no idea how to be animation assistants or clean-up artists – the entry level jobs that would get us into a studio.”

Kate Wallis9 was already in Ottawa but started her TV life at the opposite, yet equally cartoonish, world of politics on Parliament Hill. Working for the morning programme Canada AM, she applied for a starting position at The Raccoons.

“And it was a wonderful experience there,” she says. “It was wonderful to be working in the days [before] we were sending digital images around the globe to save money. I remember the first time we decided to send cell to be opaqued overseas. We sent them by FedEx after the inking was done and they came back by FedEx but they hadn’t been sent in the right shipping area of the airplane. And when those boxes were opened, all the paint had popped off all the cells so we had boxes and boxes of cells, essentially unpainted, and paint chips – pound and pound of paint chips.”

“We remember Rocket Robin Hood,” she adds. “We remember stuff we saw as a child the way we remember nothing else. And I wanted to be a part of making that really good.”

Mr Waldren says the first episode, treated as a special, allowed plenty of time for junior animators and assistants to learn and get it right, from storyboards and recording, to splicing, cell painting, backgrounds and more, before it became cheaper to send work to the Far East. Gradually a library was built up of backgrounds and character expressions that could be reused as the series went on, streamlining the process.

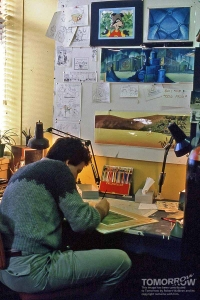

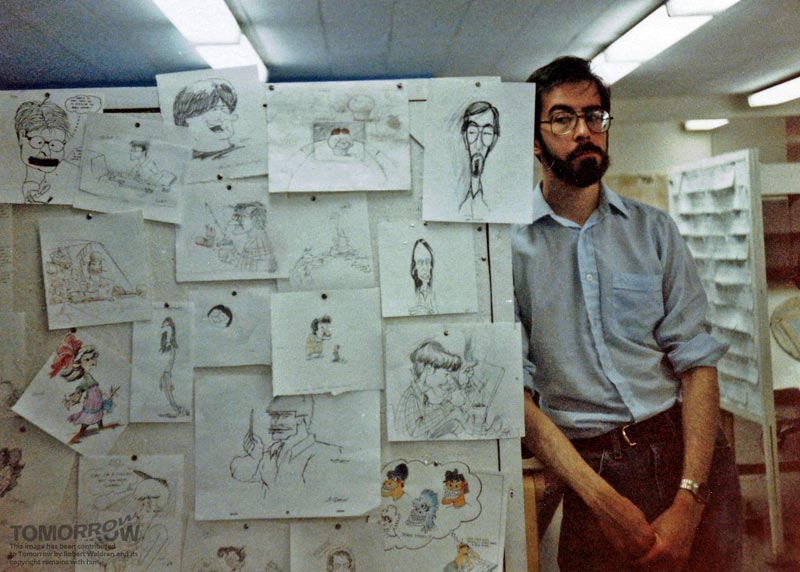

Storyboards were pinned up around the studios so everyone knew what they were working towards, with the first episode taking up to four months – everyone remembers it taking a different length of time. There were self-deprecating and show-deprecating sketches as well.

A team of eight writers put together the scripts with funders CBC and Telefilm Canada having approval of shorelines. The Raccoons reportedly took hockey advice from Hockey Night in Canada’s Danny Gallivan and the New York Islanders’ Mike Bossy.10

And the music for the TV series, as with the three specials that came before it, was from the National Arts Centre Orchestra, led then by John Gazsi, who died in a car crash in 1984 and was the origin of the dedication still seen at the end of all the first season episodes, now sold around the globe. Gazsi’s name also lives on in the Friends of the National Arts Centre Orchestra John Gazsi Memorial Award, presented annually for 30 years at the Kiwanis National Capital Region Festival. It was won this year by Ethan Balakrishnan.11

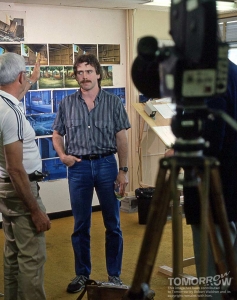

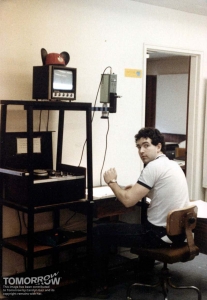

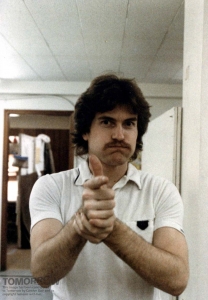

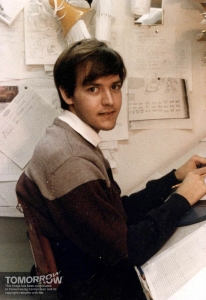

Nik Ranieri – and the real one next to him in 1985.

From ball hockey to bank robberies, animating for The Raccoons was about more than technical skills – it offered life lessons as well, as Mr Ranieri admits.

“There was a lot of things that had to be sort of excised from your expectations,” he says. “I eventually did get promoted to animator just like some of my colleagues as well. But for the first one or two shows I think, I was still an inbetweener. I was very cocky. It was one of those situations where I would rate the animators on how they did – I felt I knew it all and didn’t need to learn anything.

“Basically the head of the assistants department, Roger Way,12 came to me one day and he said, ‘Look Nik, you have an ability to animate, but if you’re going to get anywhere, you’ve got to change your attitude and you’ve got to start being a little more respectful’.

“And I didn’t think I was doing anything wrong at the time, obviously. But in hindsight, you just don’t treat people like that. From those experiences I learned people skills and I was able to take that into my next job as well.

“There was a point in time in the Raccoon show, I think it was episode seven, I was working on a Cyril Sneer scene and he was in a boat and he was yelling at somebody and grabbing the pig and shaking him or something like that and I brought the scene to [storyboard artist] Chris Schouten13 and he looked at it and he goes, ‘Nik it’s a really good scene, I really like it, but there’s just too many drawings’.

“And at that moment I knew it was time for me to leave and I knew I needed to expand my knowledge and I went as far as I could on that show, as far as honing my craft.

“I wanted to work on fuller animation that was bigger budgets, features. At that point we were all gung ho – a lot of us were really jazzed about animation.

“A bunch of us got together during the production and we actually wrote a script for the show and we submitted it and gave it to Kevin Gillis, who rejected it. But we spent evenings writing this thing just because we thought, ‘Let’s try to make this show something cool and we had this great idea and maybe he’ll buy it’.

“They didn’t want to hear from us. And then after that happened, a lot of us got discouraged and we started to look elsewhere.”

Was it truly Canadian?

The first appearance of Bert, Cyril and gang was in The Christmas Raccoons in 1980 after Mr Gillis and Ottawa lawyer Sheldon Wiseman sold it to CBC and stations in the US. A huge success, it was followed by The Raccoons On Ice in 1981 and The Raccoons And The Lost Star in 1983 before a first series gained a reported $4.7 million in funding from Telefilm Canada, the Walt Disney Co, Embassy Home Entertainment and others.14

Airing first in the United States, the first episode of the 11-part run debuted on October 21, 1985, and achieved 1,734,000 viewers in the prime-time, 7.30pm slot, according to Nielsen ratings published at the time.

By the second episode on October 28, the numbers climbed to 2,280,000 million, of whom 1,710,000 were aged two to 11.

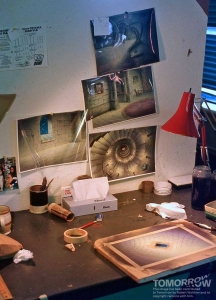

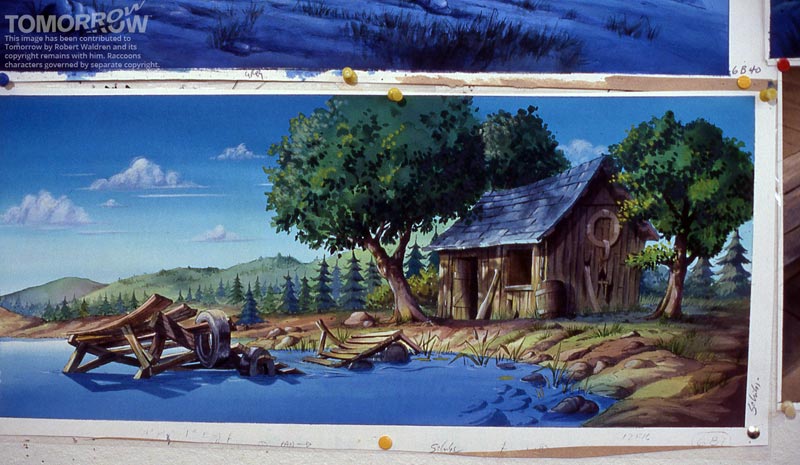

The backgrounds captured the beauty of the Evergreen Forest.

At the time, Kevin Gillis15 – the show’s then 35-year-old creator who wrote much of the music and oversaw the scripts, colours and merchandising – said raccoons became more human than rodent: “The characters grew from childhood memories of what certain people reminded me of – as well as looking at my own personality. You tend to hold your characters around people you like and people you wish you were like.”16

Mr Gillis recently announced he was looking to restart the show for a new generation. He did not reply to an interview request for this feature.17

Sheldon Wiseman at the time argued the show wasn’t Canadian, just the quality.

He told the Ottawa Citizen in 1984: “There’s nothing distinctly Canadian in the show. It could be Northern Ontario or South Dakota. But there is a Canadian perspective to the production. It’s the same quality that has caused a disproportionate number of Canadians to be successful in American television and films.”18

But did the soft environmental message – the various storylines about protecting the forest from money-obsessed, cigar munching Cyril Sneer – make it Canadian? Or was it the setting in a forest or animals? Why did that work for international audiences?

“I think what is distinctively Canadian does connect with people,” Ms Wallis tells Tomorrow by phone from Ontario. “It was distinctly Canadian – its messages.

“And it seems The Raccoons – I hesitate to characterise Canadians as wholesome – it was kind and big hearted and funny and not without an eye to the evilness of Cyril Sneer and capitalism and ulterior motives. But I think in the end the messages were of kindness and acceptance and inclusion and, I think that that’s certainly what Canadians like to think of themselves.”

She adds: “Maybe part of the reason that the show had the impact it had was the tremendously high quality of the animation. It was done by excellent animators – not that there aren’t many overseas but I think often times there’s a communication break that lessens the fine interpretation of expression, of body movement.

“If you send a tobogganing scene to Korea, you don’t get the same subtlety of understanding that you do from a tobogganing scene done in Ottawa where half the year they’re tobogganing. It’s our human experience to do winters and to do those things. I think it benefited from that and I think people felt that and recognised that, even at an intuitive level.”

Robert Waldren doubts The Raccoons, if made today, would be Canadian.

“I kinda doubt that. It would be set in Vermont now, not in Gatineau Hills,” he says by Skype. “It has to be recognisable around the world and you have to worry about your markets in the Far East and everybody knowing what you’re talking about. There are still people who don’t know that it’s set in the Gatineau Hills and that sort of thing, but it was. It was designed that way to be a Canadian show.”

“We’ve got everything you need” – almost

It was “truly a golden age in the Canadian animation industry” says Tim Deacon. Ever since, the animation and games worlds – and a few other professions – have been full of Raccoons alumni.

After Raccoons, Carolyn Gair worked in Vancouver for a few years but before animation took off in the city, returning to Toronto to work on the Babar TV series with Nelvana and then productions in the US.

Nik Ranieri says many on The Raccoons focused on getting work in the US and he eventually made it to Disney, working on some of the most well-known animated characters of his time. His 25 years there came to an end in 2013 when a team was made redundant but found a role with The Prophet,19 out in the US on August 21, 2015. He is now involved in the gaming industry, producing World War Toons.

Gerard de Souza left for a period and then returned in 1988 to the show, later working for Disney Canada when it expanded north for a period, worked in gaming for the company that became Electronic Arts Canada, taught and most recently worked on The Prophet with Mr Ranieri.

“But I’m kind of an odd duck,” he adds, “because I’m 53 years old and I’m working with people who are my childrens’ age, in their early 20s, and co-workers – they’ve been a great help to me technically and I go off on tangents telling them my curmudgeonly philosophies.”

Robert Waldren says animation is making a comeback, particularly with networks such as Disney XD, Cartoon Network and Teletoon insisting on “lively animation”.

“It’s cheaper to be done here rather than overseas,” he explains. “It’s gone back to more of the spontaneity that really was lost for a while. It kbecame very homogenised.”

Karen Munro-Caple was picked up for The Raccoons while volunteering at the International Animation Film Festival in Toronto, rising eventually to the role of animation director, learning both animation and diplomatic skills. After The Raccoons she worked on TV and film productions such as Babar and The Railway Dragon. But she later turned to a different path.

“I loved the people and the expansive creativity that those studios encouraged,” she tells Tomorrow by email. “I did grow weary of other people being in control, over producing, no money, they want it yesterday… after a while I had enough and started my own massage therapy business.”20

The camaraderie, almost growing up together as young animators, has kept connections going for three decades, say animators. Ms Wallis is currently production managing Dark Sunrise, a live-action film from Hilary Phillips and Greg Gibbons, who both worked on The Raccoons.

“I don’t think I’m romanticising it at all,” insists Mr de Souza. “I have a lot of fond memories of it, and I was too stupid to worry about what I was getting paid and I have a lot of fond memories of the people and the work.

“And I’d be saying this even if I didn’t reconnect with them on Facebook – we seem to be buddies for life. A lot of warm memories, a lot of things, and I think it informs a lot of my opinions of animation and I think a lot of animation today is overworked and over-produced and a lot of redundancies, that I didn’t experience when I first experience, like I keep going back to that and liking it to be that way.

“And I would love to work again where everything happens under one roof and everything is sympathetic towards the animation, talking department wise, artistically. It was a very positive experience. And friendships that seem to have lasted a lifetime.”

Animation – “Sinking in quicksand”?

“You’re just so happy to see your name in lights, as corny as that is, for a ‘stupid TV show’ – you see your name and your family sees your name and years later people see your name. It was a thing,” Mr de Souza says.

“There’s the people who do the layouts, and then people who do backgrounds and people who do character animation, people who do the inbetweens and people who paint the cells.

“So many hands touch a scene and my brother tells me the story my dad was watching it and says, ‘Hey, is this the show Gerard worked on’ and my brother goes, ‘Yeah it is’ and like 10 minutes later my dad’s going, ‘Yeah, it looks like his style’. Like he thinks I did the whole show or something.”

But the pay wasn’t glamourous, he says. When he started in 1984, he was paid $5.50 an hour, rising later to $7.21, scraping together enough money for rent with his wife working as well. Assistant animators or inbetweeners on The Raccoons got salaries, as did background artists and layout artists such as Tim Deacon. Others, such as Carolyn Gair, were paid by the foot. As she explains it, a foot of animation was 16 frames or eight hand-drawn images; one second of animation was a foot and a half or 12 images. An average animator could put out about 20 feet a week, as Ms Gair did. Mr de Souza boasts he remembers once animating 99 feet in a week, but thanks to a great deal of stock and reused material.

As well as the mix of approaches to pay, there were machinations of production firms. Atkinson Film-Arts, which had worked on the first TV specials, did the animation for the first series, after which Hinton Animation Studios took over, and pulled away many of the Atkinson staff. Atkinson was shut down in 1989 over debt problems. Hinton, later Lacewood Productions, eventually suffered the same fate.

“I can’t bemoan animation or hand-drawn too much because we’re not the only ones that are facing extinction,” says Mr Ranieri. “My feeling has always been that just because somebody invented the camera, doesn’t mean people stop painting. I’m hoping, eventually, people will understand that and that 2D can survive.”

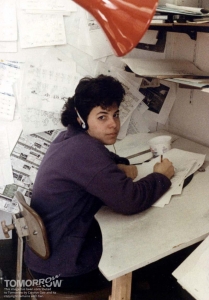

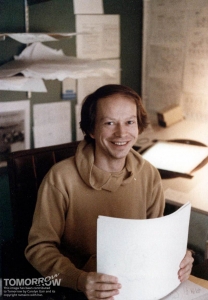

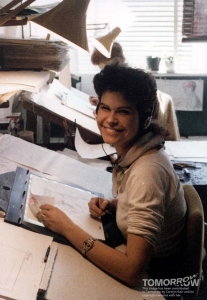

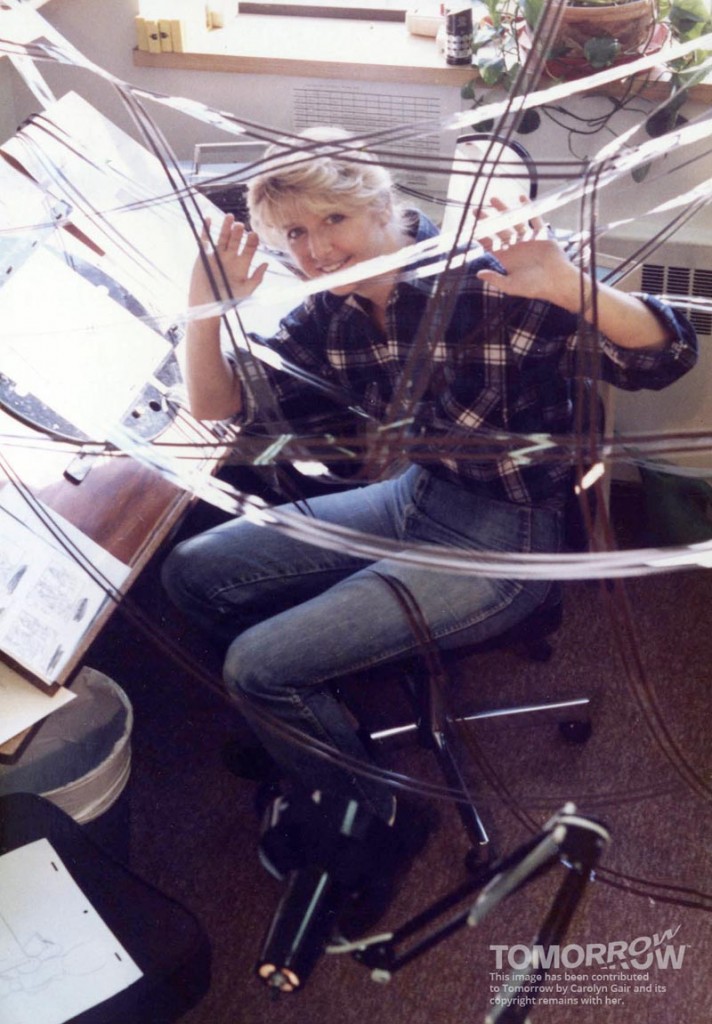

Carolyn Gair at The Raccoons after colleagues crossed her desk with 16mm film as a joke.

Ms Gair adds: “I wish there was more of a future for Canadian animation, but mostly these days it’s outsourcing for American productions. I wish there was more of a film movement there, though I’m pretty happy as an ex-pat at small successful American studio.”

As well as changing production methods and studios, the pay for writers has declined in recent years, explains Ms Wallis. Where 15 years ago a project might pay $5,000, it now offers between $1,000 and $1,500. If people are paid less, their input is valued less.

“I think that it’s too bad television in general – and children’s especially because there’s such a wonderful scope for creativity – suffers very greatly from the tentativeness of finances to back a new idea instead of just producing a book for the screen,” she says.

“I really would love to see the days where someone would take a chance on something called The Simpsons or still take a chance on The Raccoons and do something really original and unique.

“And with the internet and with the advent of technology, if I wished to sit down at home with Flash and make my own animated series and everyone in the world could see it. . .that’s an advantage. But I’m an old-school girl and I miss the television slot with the good, good animation in it.

“If you look at early animation of The Simpsons, it’s just awful, technically, but the scripts and the performances are really the core. The story and the voices we hear telling that story are really the very core and and basis of excellent television, of any sort.”

What’s up with the aardvarks?

“The forest. . . and the aardvark – I don’t know what the hell the aardvark. . but I think it’s part of the charm, the incongruous of aardvarks in a castle, in Canada – it just stays with you, like what the hell?” says Mr de Souza.

“There’s something a little bit smarter about it. There was this kind of insipidness there of other properties like Care Bears, the Rainbow Brights and the My Little Ponies – very sweet and safe and the first thing I thought was The Raccoons was a little smarter in its writing and stuff. There was some corny stuff, but a little smarter and something a little different and not as formulaic I felt.

“Nowadays it’s just normal – it’s almost synergistic now: it’s not a toy based on a TV show, it’s not a TV show based on a toy, it’s just kind of all in one.”

Mr Ranieri admits he is surprised at the enduring popularity of the show, but wonders if it’s the power of memory from childhood.

“I never thought it was that great a show,” he says. “In fact we used to mock it while we were on it – because it was limited animation.

“I had this experience when I went up to Canada to work on The Prophet. There was a production manager there, and you know, I worked for Disney for 25 years, I worked on Beauty And The Beast, Little Mermaid, Roger Rabbit, Pocahontas, all these things, but she was mostly overwhelmed by the fact that I worked on The Raccoons. And I’m like, ‘Really?’

“I have no idea why it’s as popular as it is. That’s a mystery.

“I mean, it’s ok – it’s not horrible, as shows go.

“Here’s a good example: a lot of things you see as a kid, you take with you and sometimes you look at these things years later and, ‘Oh that’s pretty lame but I was just a kid’.

“But other things you look at and you still like them, even though they might not be very good, there’s a fondness there. It all depends on what you grew up with.

“If I were think about it now, I guess the attempt on The Raccoons was to at least make shows that had some sort of different story about it every week, that tried to have a little bit of social comment in it or something like that. Kevin Gillis seemed to be a person who really cared about the show.”

TV production schedules required that shows had to be turned around faster than a feature film, leading to fewer layers in the animation and some “wonkyness” as Mr de Souza describes it. He sees a beauty in the imperfection and limits of The Raccoons.

In one example, the Xerox process for cells could melt and stretch them a bit, leading to a certain wobble in some of the shows.

While some of the rough edges were caused by technology, animators would also slip in their own styles. Mr Ranieri says he and others played with stretch drawings as students and on the show would see what they could get away with. In one episode where Bert Raccoon was playing pirate and says, “Yo ho ho and a bottle of pop”, Mr Ranieri added a “snarky look” from the pigs then hiding behind a building. “Social commentary on the writing,” he says.

“I probably should have stopped when I left,” he adds. “One of my most embarrassing things I did when I got to Disney was I actually did [a stretch drawing] on one of my first Ursula scenes and to this day I see it on The Little Mermaid and I regret doing it because it seemed so out of place for a feature. For TV animation, it worked fine.”

Mr Waldren says it’s a mix of qualities that has helped The Raccoons endure, from characters and storylines that mixed crocodiles and aardvarks and raccoons in the Gatineau Hills, to slapstick and songs.

“But it had a kind of a sincerity I guess you would call it, that still seems to work,” he says. “Because there were animators who were running the show, they allowed for spontaneity, especially from their star animators, and so there’s always a little, in most of the shows, there’s something a little extra and a little funnier and a little different looking as well as the overall kind of homogenised look that keeps the story going. I kind of like that.

“It has a personality.”

“I see passion in your eyes”

Raccoons alumni have moved with the times and learned different types of computer animation, but never abandoned their love of the traditional that has kept them going since their first working days 30 years ago.

“There’s something beautiful about traditional,” describes Mr de Souza. “And computer animation back then did have a too-perfect, smooth reputation. It was chrome balls and checkerboard patterns and robots moving robotically.

“Computer’s become a necessary evil I had to do to make money and support my family.”

The technology has changed the relationship between the animator and the image, he says. As a student and later on The Raccoons, you would shoot the animation, hope it matches with the lip-syncing, go back and make changes, shoot it again, and keep working at it.

“When you’re working on the computer you’re getting all that feedback, not to mention also the easy access to references for animation,” says Mr de Souza.

“You’ve got whatever you want – type it in into Google and you’ve got a reference to how this animal moves or how this person runs or this person walks. And I kind of mourn this loss of many of the really great animation out there, even the cartoon stuff. It’s very reality based. It can be more exaggerated.

“Whereas before you had access to that reference, you had to think, ‘Ok, I saw a guy run once, how did he do that?’ And you get a very impressionistic thing happening when you’re finished with it.”

Ms Gair is a storyboard artist for the upcoming film Rock Dog21 featuring the voices of Luke Wilson and J K Simmons. And she creates a stop-motion animation every day for Instagram,22 as she did for this article.

“For me, my stop motion films for Instagram are ‘instant gratification’. I come up with an idea, I execute it, I edit the timing, add music and, Bam! Post. I have created a miniature film. I do it because, ultimately, I have created another world. And I invite people to look in and be a part of something that only exists in the realm of imagination. Animation is the suspension of disbelief – my favourite place. I make life out of the inanimate, like growing clouds out of thin air.”

“There’s nothing to compare to the experience you get with actually handling animation, and I mean pencil and paper, flipping it classic style,” agrees Robert Waldren. “To go in and draw the characters, moving in space, that’s what we did for almost eight years in Ottawa and you can’t duplicate that experience.”

Animation is personal, organic even for the artists, and for the audience. Mr Ranieri says after working on Meeko, another raccoon, on Pocahontas, he was sent a news clipping about how a boy saved his brother’s life from drowning in the bathtub by pushing his stomach, just as Meeko does to Flit in the film.

“Every now and then stories like that come up and you’re just like, ‘Wow, these films have an effect on people’. And usually it’s just entertainment but every now and then there is a lesson to be learned. In that way, it’s been pretty rewarding,” he says.

The quality of The Raccoons might not be consistent from scene to scene, admits Mr Waldren, but they were learning as you went along and the originality in the shows was a good thing.

“There’s a lot of scenes that are very spontaneous,” he adds. “There are tones of scenes where you can tell exactly who worked on them because they drew the character a certain way and their animation was a certain way and it had an individuality. And I think it’s part of the reason why the show itself is still very popular. It looks handmade.”

- The Raccoons, 1985-1992. ↩

- Sheridan College’s faculty of animation, arts and design. ↩

- Gerard de Souza. ↩

- Robert Waldren. ↩

- Nik Ranieri’s public Facebook page. ↩

- The Colonel By Towers building. ↩

- Tim Deacon at Smashing Animation. ↩

- Carolyn Gair. ↩

- Kate Wallis, as Laura Kate Wallis. ↩

- Mike Bossy’s NHL career. ↩

- Ethan Balakrishnan and Friends of NAC Orchestra. ↩

- Roger Way. ↩

- Chris Schouten. ↩

- The Ottawa Citizen reported funding as both $4.5 and $4.7 million in articles in 1985. ↩

- Kevin Gillis’s current production firm, Skyreader. ↩

- “‘The Raccoons’ steal a few lessons from life”, TV Guide, October 19, 1985. ↩

- Press coverage of planned reboot. ↩

- “Film company skating on solid ice”, Ottawa Citizen, November 2, 1984. ↩

- The Prophet movie. ↩

- Karen Munro-Caple, massage therapist. ↩

- Rock Dog film. ↩

- Carolyn Gair’s Instagram animations. ↩