This investigation contains words, images and videos which may be offensive to some readers

Filming freedom and fear

Film4 in the UK, the television sister of a film production company,1 airs classic Western films regularly.

Dumped in the mid-afternoon as opposed to prime time, the films make use of every stereotype created by Hollywood over several decades, particularly of the white woman needing rescued and frequently with white actors playing Indigenous roles. Drums Along the Mohawk (1939), aired earlier this year for example, shows the women defending their fort from attack, gleefully pouring boiling water over the invading “savages”.

Film4 told Tomorrow: “Westerns are happily a consistent part of our weekday afternoon schedule, with titles from the 1930s to the 1960s.

“A small number of the Westerns have had minor edits to make to them to make them suitable for slot.

“Films of the past are never taken for granted and always need to be reappraised. We’re conscious of the way that Indigenous people are treated in older Westerns made anything from 50 to 80 years ago and these films are constantly reviewed in the light of current sensitivities.

“However, film history is also important and the channel seeks to present films in as integral a form as possible, mindful that cultural norms may be shifting. The Western genre is well-known and understood, and viewers seem well able to understand the context and historical standing of these films. We have never had complaints about Westerns shown on the channel.

“To sum up, we are concerned about this issue and review the films accordingly.”

As well as brief, fleeting glimpses of Indigenous objects or culture across advertising, the UK is also exposed to lengthy narratives about conquered peoples. But they are not just passive depictions, and in places such as Germany, they have been used for much more political ends.

Propaganda wars

Dr Frank Usbeck is a post-doctoral research fellow based at TU Dresden with an interest in Indigenous culture and history, particularly how the “frontier” has been depicted and used over the last century.2

Frontier history and its imagery have been tied to cultural practices in Germany and even political ideologies, he explained, with a fascination with Indigenous peoples as information passed through the German centres for printing.

“As soon as Europeans knew that there were Indigenous peoples in the Americas, Germans talked about them,” said Dr Usbeck. “And Germans were fascinated about them and came up with pre-conceived notions about them.

“And also as soon as Germans talked about Indigenous peoples in the Americas, they were quarrelling among themselves who had the authority to make correct depictions of these people.

“The quest for talking about the ‘real Indian’ or the ‘authentic Indian’ as H Glenn Penny described it, has been going on ever since the so-called discovery.

“However, it became a big feature in the Germanies in the late 18th century or sometime around 1800 and that has to do with the emergence of German nationalism.

“From the beginning, talking about Native Americans in Germany is tied very closely to a quest for the self – discussing ‘who are Native Americans’ since about 1800 has been a large part of asking what makes Germans German, what is German?”

[Tweet “”‘Who are Native Americans’ has been a large part of asking what makes Germans German””]

The comparatively late development of a German national identity led people to seek similar traditions to their own “tribal” origins, said Dr Usbeck. They concluded they could relate to Indigenous peoples in North America because of their own experience with “having to fight back numerically and technologically superior invaders, people who come in and tell us our culture is primitive, our technology is primitive, we don’t have the right religious beliefs and we should change our ways”.

In their view of history, German tribes had to battle the Roman Empire, then the Roman Catholic Church, then France and by the time of the founding of the Kaiserreich in the 1870s, the narrative about a people battling for survival was well entrenched. And by World War I, American imperialism, British colonialism and French aggression were seen as direct parallels to what happened and continued in North America.

There evolved an “Indianthusiasm”, a term developed by Canadian studies scholar Harmut Lutz3 to describe the fascination for Indigenous peoples, something both constant through different political regimes and war propaganda, but also malleable to suit their needs.

It could appeal to Germans from different walks of life, social backgrounds, regions, during the Kaiserreich, the Weimar Republic, the Nazi era, and beyond into Communist East Germany, West Germany and even in the resurgence of far-right groups today.

Dr Usbeck described the theory as: “We and Native Americans have common enemies and on top of that as descendants of a tribal people we have similar group character traits that we share with Native Americans’ and supposedly only Germans can understand Native Americans very well.”

Novels featuring the character Winnetou by Karl May were published between 1875 and 1910 depicting a lone character always looking for “white people he can help” and who eventually converts to Christianity on his deathbed.

Dr Usbeck said: “The original novels, there is some element of longing for freedom at the frontier, going away from the constraints of German bourgeois society – while at the same time everything in those novels promoted values that represent a German bourgeois society.

“They were very simply and clearly about good versus evil in which evil is always punished and good always prevails, in which even Winnetou, the Native character, exudes those very, very German bourgeois ideals.”

When the novels received a cinematic adaptation in West Germany, they proved so popular that East German state-owned productions cashed in on Indigenous topics. They didn’t use Karl May, but portrayed Indigenous peoples as victims of American imperialism, where critics drew “clear parallels” to the Vietnam War.

“The East German government drew their own conclusions and used the imagery of good versus evil for their own political and ideological means,” explained Dr Usbeck. “As a Nazi you could use Indianthusiasm in very different ways as well – you could blame the Americans for their colonialism. And it was fairly easy for Germans to do so because Germany did not have colonies in the Americas, and they would just stay very quiet about German genocide, for instance, against the Herero [and Namaqua] in South West Africa, in the early 1900s.”

Joseph Goebbels’ Nazi propaganda ministry in 1938, described Dr Usbeck, countered articles about German treatment of Jews, such as with Kristallnacht and the pogroms, and redirected attention to Americans and their Indigenous peoples.

Two weeks before Kristallnacht, the Chicago Daily Tribune published an article headlined: “Remember Fate of Indians, Nazis Tell Roosevelt”.4

And just days after Kristallnacht he directed reporters to go freely criticise US-Indian policy in response to outrage about the pogroms.

American journalist Fletcher Pratt, published a piece in the American Mercury referencing massacres of the American Indian, which was then promoted by Goebbels’ ministry.

It said: “A mirror was held up to the Americans, they were shown that the entirety of American history is paved with murder, arson, robbery, etc. It was an answer to the Americans from an American source, which preempted a necessity for our own answer [to US outcries over Kristallnacht].”5

And while militarism and race cards were both part of the propaganda, so too was the connection to the environment. It was argued National Socialism, as the application of natural law, left a duty to protect the environment as it was tied to “national character”.

Dr Usbeck continued: “And there have been instructions, for instance, where schools were given areas in the forest, and teachers were instructed to take the kids out for outdoor instructions, teach them about healing plants and animals, tell them ancient legends about German ancestors who used these plants and animals and in this instruction teach German children how to cherish their home environment and how that is supposed to build up their pride – their national pride and racial pride.

“Many educators also made the reference – and you see that in newspaper articles about Native Americans – where people explicitly make the parallel, saying, ‘The Indians protected nature, we protect nature because we know how to do it and we don’t trash our environment as the Americans are doing’.”

Dr Usbeck said the Nazis didn’t have to steer thinking too much. They merely took the interests of the populace and existing imagery and promoted them to fit their ideology, keeping quiet when there were contradictions.

And the same imagery is being used now by the Lega Nord in Italy, the FPO in Austria and others. The references to historic frontier massagers such as at Wounded Knee and Sand Creek were used by the Nazis after they declared war on the US and are still used by far-right groups and politicians citing variations of, “They [Native Americans] suffered immigration: Now they live in reserves”. 6

Dr Usbeck said similarities between anti-immigrant forces in the US, and German neo-Nazis demonstrated how nativism and xenophobia and racism used Indianthusiasm for “distinctly national problems”.

“Colonialism from a Native American perspective is used to denounce multiculturalism and immigration in clever ways: to infiltrate an Indigenous people and destroy its culture and society from within and eventually take that nation’s land base until the Indigenous group is pushed to the side and sits on small patches of land – reservations – where they are strangers in their own country and a minority.

“That is done very, very explicitly,” he said.

In modern Germany, this is a contrast between the mocked Indigenous figure and the supposedly more respectful but ultimately still stereotyped portrayal.

The German ad for Kytta-Salbe Indianer, which used Native American actor Sam Bearpaw, aimed at the idea of “fierce and stoic warrior – the notion that an Indian knows no pain or an Indian never cries”.7 It’s an image Germans could relate to and “makes total sense” in selling pain-killer medication.

“I would also think not many Germans would see that as a derogatory or a diminutive depictions of Native people,” commented Dr Usbeck.

Screen grab of Bravo Otto awards showing Taylor Swift with her past win. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

On the other side are the periodic Bravo Otto awards, given out by Bravo magazine in Germany and other European nations, with their Golden Otto, a small caricature of an Indigenous boy. Past winners have included celebrities Olly Murs, Rihanna, Justin Bieber, Selena Gomez and Taylor Swift.8

Dr Usbeck noted one counter aspect of how Indigenous imagery and peoples were used in Germany: a welcome and a support for Indigenous peoples, for example with issues such as cultural appropriation.

He said: “That’s in the tradition of siding with Native Americans, in Germany, to begin with. So if you look at movies, most Germans watching a Western would root and would have historically rooted for the Indian characters.

“And it’s always interesting for me to read accounts of Native Americans and so on, how much of a revelation that is to Native people to come to a place where a you’re not the pariah automatically and where you don’t have to defend yourself but you are considered the pop star. Which has its own problems obviously, but it is a huge difference.”

And while there remains a large Native hobbyist movement, Indigenous peoples also made use of the German market for goods and traditions, for example with “Wild West” shows in the 1880s through to the 1930s. There has been, in turn, debate back in North America about whether ceremonies such as Sun Dances should be closed to German tourists. And there has been debate about how much “agency” the “performers” of the past had when using or being used by Germany.

“Some Germans would see that this is outright commercialism and we do not accept it,” said Dr Usbeck, “and on the other hand sometimes people don’t see it and let themselves be baited by the Native image dangling on front of them that they know, that they want to see and want to see confirmed.

“There are currently Native people who live in Germany who tour schools and zoos and tour local country festivals to perform, do dances, do whatever like knife throwing and archery workshops and stuff like that – who basically make a good living off of the ongoing fascination with Native American topics.

“We should talk about how ethnicity is being commercialised, and appropriated and exploited – yes. But at the same time selling ethnicity is very often the best way, sometimes the only way, for an ethnic minority to make a profit, or to promote their cultural and ethnic identity.

“Who does the selling? Who does the promoting? If Native people have control over that, be it travel tourism or be it Indian gaming, then those are immense economic opportunities for that group which can in turn be transformed into cultural opportunities to continue your cultural identity.”

Back in North America, Scott Frazier can’t help but laugh at those wanting to buy the Indigenous items.

“For me, if they’re buying those things they’re just in love with images that seduce them away from their money, again,” he laughed.

“The European loves the image of the free Indian because they’ve never been free. The European has always struggled with that understanding because there’s always somebody in the group that wants to be the leader and control everything, which defeats the purpose.

“So when they see that Indian and the image of the tipi and all of that, it’s an image of freedom that they just don’t understand that that freedom was strangled out of the Indian. We’re not free anymore.”

‘They don’t want our struggles’

Dating back hundreds of years, the Two Row Wampum belt was one of a number of similar defined relationships between Indigenous peoples in North America and the invaders, of two nations separate but equal.

That continued to be a general approach of trade and military relationships and underpinning treaties which applied to about half of Indigenous peoples. They pushed non-interference that lasted into the initial years of the “Indian Department” for British North America.

But the desire to settle the “free” land with settlers increasingly displaced old military alliances that were less crucial after the war of 1812. So British-born leaders began setting up a system to “civilise” Indigenous peoples to assimilate them into white, Christian society, ultimately taking their land and, in theory, eliminating the need for an Indian Department.

In a series of pieces of legislation before Canada formally came into being in 1867, the definition of who could and couldn’t be “Indian” began. Limits were placed on traditional government, with supervision from government and encouraging private land ownership.

The “warrior” image, still celebrated today in the use of headdresses and “freedom” depicted in German film and anti-immigrant propaganda, was replaced with a stated goal of no distinct identity at all – or rather, an imposed one.

In the preamble to the Act for the Gradual Civilisation of the Indian Tribes in Canada, 1857, it stated:

“Whereas it is desirable to encourage the progress of Civilization among the Indian Tribes in this Province, and the gradual removal of all legal distinctions between them and Her Majesty’s other Canadian Subjects, and to facilitate the acquisition of property and of the rights accompanying it, by such Individual Members of the said Tribes as shall be found to desire such encouragement and to have deserved it …”9

Legislation in 1869, after confederation, meant women who married non-Indigenous men were no longer “Indian”, nor were any children born to the union. The US similarly created confused legislative and judicial decisions on who was, or wasn’t, pure or “status”.

It was the Canadian 1876 Indian Act that pulled everything together and has continued to affect almost every aspect of Indigenous life since, from taking lands, to children from their homes in the “60s Scoop” and through the modern care system, to thousands who were abused and died in the residential schools system. Despite campaigns to scrap it entirely, successive governments have only tweaked the Indian Act, most recently with a promise to end the rules defining status by sex.10

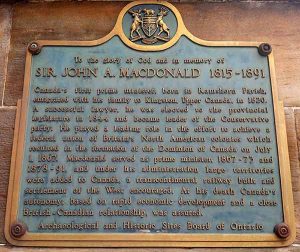

David Laird, son of a Scot, pushed through the Act during the prime ministership of Alexander Mackenzie, born in Perthshire, Scotland. In 1884, Prime Minister and Superintendent of the Indian Department, John A Macdonald, born in Glasgow, pushed the banning of traditional ceremonies, such as the potlatch, and cultural items.

In Glasgow today, he is remembered with a plaque citing “under his administration large territories were added to Canada, a transcontinental railway built and settlement of the West encourage. At his death Canada’s autonomy, based on rapid economic development and a close British-Canadian relationship, was assured”.

Plaque marking the area in Glasgow, UK, where John A Macdonald, first prime minister of Canada, was born. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Despite the treatment by the British Crown, there were communities which still maintained their alliance. When World War I broke out, a battalion from Six Nations of the Grand River answered the call, travelling to the UK and touring various centres where their different appearance was both celebrated and denigrated.

“The presence of the chiefs in their barbaric attire amidst the monuments of ancient feudal life in Scotland presented by the Castle and the Old Town, inevitably stirred the imagination.”11

And when the members of the battalion returned to Canada, they were forced to choose between their Indian status and that of veterans: are you Indigenous or not?

In the decades that followed, communities have been forcibly moved, children ripped from their mothers’ arms, women have gone missing or been murdered with little interest or casual indifference by police and wider society, dozens of nations within Canadian borders don’t have clean drinking water, rates of incarceration are higher, rates of disease are higher, there is a suicide crisis in many small communities. Each of the acts by the state and society have resulted in death.

Does Britain maintain any responsibility? The Canadian constitution was only repatriated to Canada from British soil in 1982 and even then, it was never signed by Indigenous peoples.

Shelley Niro said the British do have to educate themselves, and the Two Row Wampum mandates it.

“That would be a very nice thing if they could be educated into the thing because they’re the ones who are benefiting from all the ‘discoveries’ that happened,” she said. “And sometimes people come here and then all of a sudden they have ownership.

“My father always used to say ‘Why do people say “Our native people”? We’re not anybody’s Native people. We don’t belong to anybody’. A lot of other people say, ‘We have to take care of our Native people’ – well I don’t think we are your Native people.

“Education would be a great thing. My daughter, when she was in high school, she had a British teacher and the British teacher in history saying, ‘Oh the British are so famous for going around the world and discovering different lands and doing all this sort of thing’.

“And my daughter, who wasn’t politicised at the time, at all, she said, ‘How can you brag about going around the world’ and she went on and listed the diseases that were brought and all the hardship that was brought with coming to different continents.

“And the teacher was not too impressed and she said ‘sit down and be quiet’.”

Ms Niro continued: “I think it [Two Row Wampum] was designed that way. I think it was an agreement drawn up and people shook hands on it, saying, ‘This is how we’ll live in this land’.

“People who came here in the beginning they needed help, they needed to be shown how to live in the cold, harsh land. But then once they got their foot in the door and made their own little village, it changed. And it didn’t change for the best.”

[Tweet “”Once they got their foot in the door and made their own little village, it changed””]

Chelsea Vowel said she wanted people from any culture to think about their own symbols that they respect and value.

“The symbols themselves are not the thing,” she said. “The parchment is not the education that you got. The military medal is not what you did to earn it – it’s just a symbol representing an achievement.

“And for us too, we have these symbols that represent achievements and it’s deeply disrespectful to go and take those symbols and use them without permission. That’s it.

“And all we want people to understand is that we can’t force you. People from outside of our culture have a lot more power than we do, they can take them all they want.

“But don’t then turn around and pretend that it’s honouring us when we’re telling you it’s actively disrespectful. I would just like people to be a bit more honest about it and say, ‘You know what? We really don’t care about your feelings, we don’t actually care about you at all. We want this thing, we’re taking it’.

“I would prefer that than having all the people hand-wringing and saying, ‘But I just really love your culture and I just really want to honour you’.”

Scott Frazier said it was a good time to think about images and talk about the stereotyping.

“I don’t know if anybody can sit down and pinpoint the exact thing why it pisses you off. Maybe it’s because you’ve been mistreated for all this time and it just continues,” he concluded.

“But it’s a good discussion. And it’s good to have people that don’t hear those discussions to listen. Will it change? Maybe, eventually. They’re all starting points.”

***

The UK advertising spending was forecast to exceed £17 billion in 2016.12. Hundreds of ads are produced and shown on TV and in cinemas. The examples in this investigation are a fraction of those.

But, they are consistent in direction at one race of people. And there is a necessary question to follow on from that: what other race gets that attention, where cultural or sacred items are donned by white actors to sell products and/or services? What other culture or race is advertised by white children for mass consumption and profit? And then, why?

Cultural appropriation alone didn’t prevent clean drinking water or effective sanitation on communities, or put Indigenous children into care or murder Indigenous women in North America. But those problems, said interviewees, stem from colonialism and they aren’t getting fixed because of a lack of education and willingness to learn.

RJ Jones concluded people wanted their symbols and culture, but without taking responsibility. And they want the public to educate themselves.

“I think they’re taking what they want to take and not actually putting effort into what is happening,” said RJ. “They want our culture but they don’t want our struggles.”

- Film4 listings can be found online, accessed on November 20, 2016 ↩

- Personal and research page of Dr Usbeck, and his TU Dresden webpage, accessed most recently on November 20, 2016. ↩

- University of Szczecin profile page of Prof Lutz and interviews about the term.All accessed on November 20, 2016 ↩

- Headline from October 28, 1938. ↩

- Quote provided by Dr Usbeck by email citing from his own book, Fellow Tribesmen, Frank Usbeck, New York: Berghahn Books, 2015. ↩

- Translation of Lega Nord poster from “Italy’s Northern League resurgent”, BBC News, April 17, 2008, accessed most recently on November 20, 2016. Variations of this anti-immigration line tied to Indigenous reservations continue to be widespread. ↩

- German-language website promoting the Merck product. Accessed most recently on November 20, 2016 ↩

- Bravo magazine website with photos of Selena Gomez http://www.bravo.de/bravo-otto-wahl-2015-waehle-deinen-superstar-362560.html and Taylor Swift with the statues http://www.bravo.de/bravo-otto-wahl-2015-waehle-deinen-superstar-362564.html. Accessed most recently on November 20, 2016 ↩

- 20 Victoria, c. 26 (Province of Canada) “An Act to encourage the gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes in this Province, and to amend the Laws respecting Indians”, June 10, 1857. ↩

- “Ottawa to change Indian Act in response to Descheneaux ruling by February”, CBC News, July 29, 2016 accessed most recently on November 20, 2016 http://www.cbc.ca/beta/news/aboriginal/descheneaux-ruling-indian-act-february-1.3701080 ↩

- The Scotsman, “Canadian Indians in Edinburgh: Chief Clear Sky at the Castle”, December 11, 1916, p9 – see “The independence battalion” for more. ↩

- “Facts on the advertising market in the UK”, statista.com, accessed on November 12, 2016 ↩