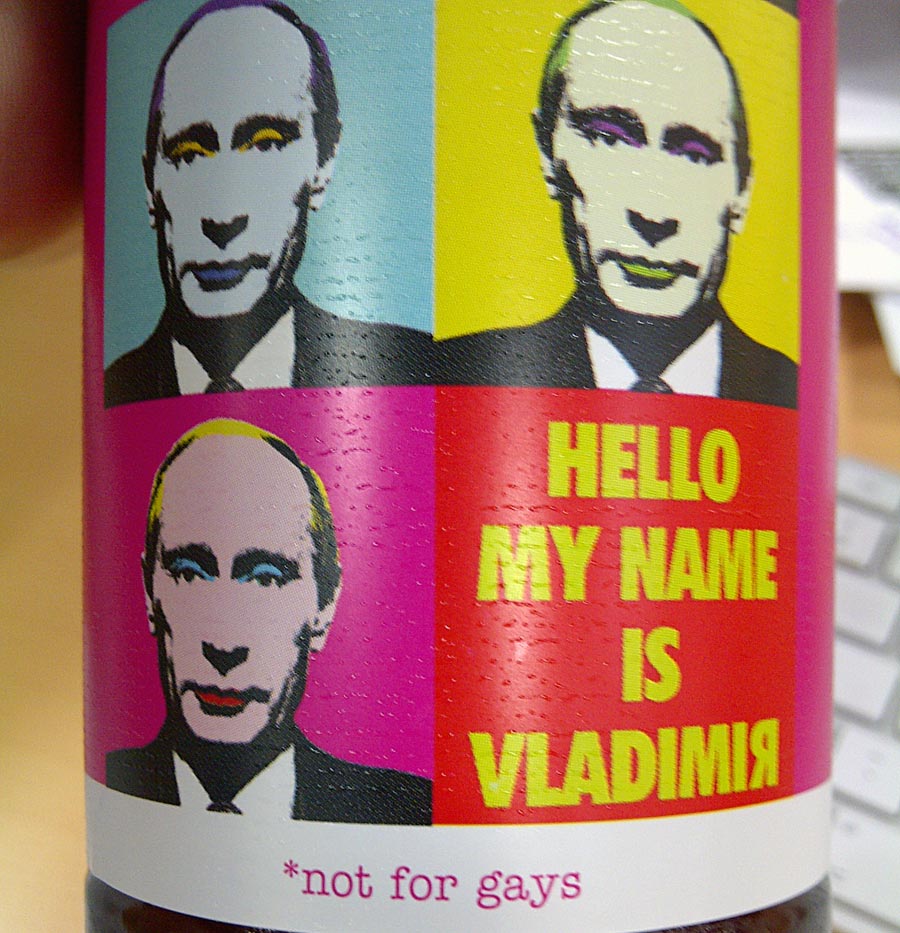

Scottish brewery BrewDog released a new beer in time for the Winter Olympics, directly targeting the anti-homosexual laws of Russia.

CAN we watch the Sochi Winter Olympics when they open on Friday?

Many of us are torn. The coverage of the rampant homophobia in Russia at the moment has been rumbling in the background for months, but a Channel 4 documentary aired in the UK on Wednesday night showed its alarming extent.

“Hunted”1 reported vigilante gangs openly going out to hunt gays for sport. These “safaris”, as they gleefully called them, are not fringe when the Russian Orthodox Church openly denounces homosexuals and the law criminalises anyone for speaking even in favour of equality for the LGBT community.

These gangs entrap innocent Russians, humiliate them, subject them to violence, and happily film it all to post online for thousands of people to revel in digital mob hate.

Knowing that there is such state-sanctioned and society-wide hate has led to many calls for boycotts of the entire games by everyone, or sponsors at least. Nothing is so simple here.

In our heads, we might know that we should keep separate the sport that goes on in Russia, and its laws and actions as a state, and separate those from the actions or inaction of its citizens. But confronted by evidence of hatred, it is hard for the heart to make those two puzzle pieces fit.

There is no nation on earth that is without flaw, without those who hate. The world allowed China to host the 2008 Summer Olympics and continue to do business with the nation, only occasionally muttering something about their human rights record.

Scotland will host the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow in July, welcoming some countries that have horrific homophobic laws in place. Their athletes will be welcomed without hesitation or condemnation. It is not necessarily a comfortable position, but it is what we’ve got.

“The sport has nothing to do with what happens in those countries,” is the theory. We compartmentalise when it suits us, and condemn when we feel like condemning.

The call to boycott, to denounce, to demand action or penalties is the new norm, particularly via social media. We post pictures of those we disagree with or fear – and this is hardly limited to Russia – as a way of silencing other humans, of saying, “This person’s voice is not legitimate and I can ignore them, while exposing them to others”.

Anyone who is in any way less morally pure than we pretend ourselves to be, must be boycotted. It is as bad as those who limit the right to assemble, whether in Britain or India or Russia or Egypt, or limit the right to speak, whether in Russia, Egypt, Iran or China. Boycotts are a limit on debate and consideration of these complex moral questions.

When someone says something you don’t like, should you turn away and ignore it? No, you must listen more, you must watch more, you must ask more questions. Apathy and complacency are this world’s greatest threat.

Tomorrow’s fifth core principle is “comfort the afflicted and afflict the complacent”. The stories you might want to ignore are the ones we must work harder to show you.

If you don’t observe and engage (principle 9), you cannot debate and improve the community (principle 11). Being a safe harbour (principle 8) and comforting the afflicted is not mutually exclusive of listening to those who want to do the opposite.

Boycotts and switching off to the moral mazes that hurt our heads and hearts are the easy things to do on social media, but they are wrong. They will not make this world better. They will not bring equality. They will not bring security to the citizens of those nations who turn on their own people as a way of distracting the masses from state ineptitude and corruption.

Do not turn away from the Winter Olympics. And do not turn away from the news from Russia when the games are over. Boycott your own apathy and your avoidance of the world’s hardest questions.