Assigning Guilt, by artist in residence Jason Skinner. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

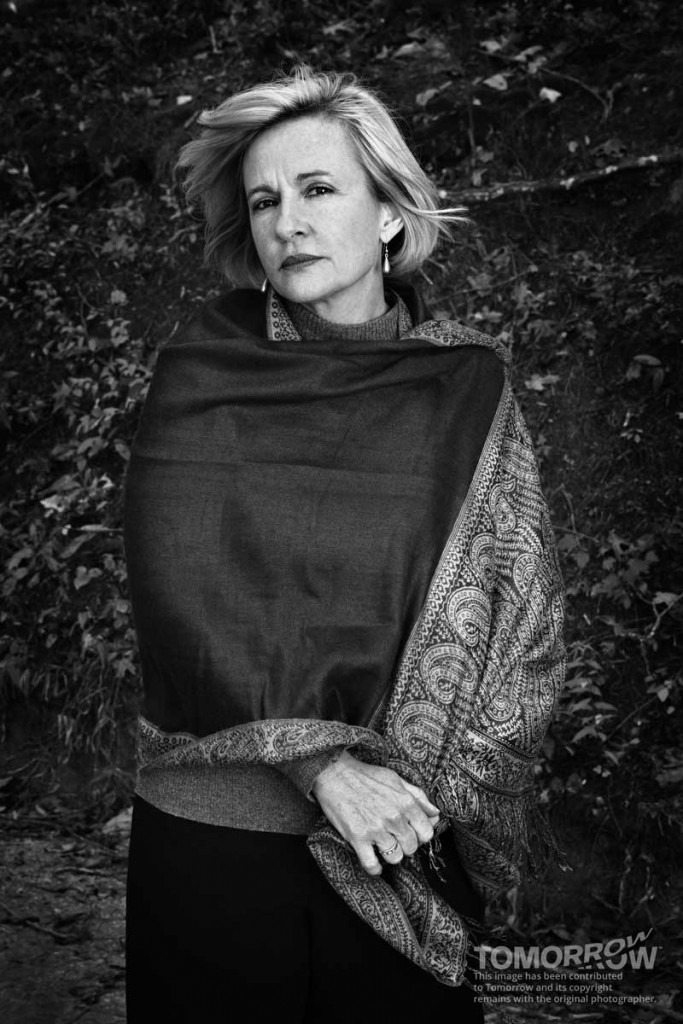

JENNIFER THOMPSON was a 22-year-old North Carolina student when she was attacked in her home and violently raped in 1984. Since then, she has seen a man accused, convicted twice and, after more than 10 years, freed after DNA revealed that, in good faith, she identified the wrong man.

She and that man, Ronald Cotton have learned how human memory and a flawed US justice system led to the mistake, and written the New York Times bestseller Picking Cotton about the redemption.1

Speaking to Tomorrow by phone from her home, Ms Thompson is unequivocal about the damage of blame.

“The big thing is just trying to explain to people that blame is so counterproductive,” she said. “At the end of the day it doesn’t add any value, it doesn’t give us what we want, it doesn’t create change.

“It causes people to bury deeper down and hunker down and defend themselves, and it just doesn’t create collaboration, it doesn’t create partnerships, it doesn’t create anything that we really need, that could potentially inform us and educate us and create change. It’s a human condition that we need to be really very acutely aware of and guard against it.

“Human beings have this gut reaction to find somebody that we have to blame, somebody has to be responsible, somebody has to be held accountable. And sometimes the answer to that is not a single human being that’s responsible or to blame.”

Ms Thompson has spent more than a decade speaking to audiences from high schools to federal judges about the systemic problems that lead to wrongful convictions. And her conclusion is that the responsibility lies on everyone’s shoulders.

She does some work within prisons, talking to inmates about why they ended up there. All accept responsibility for their crimes, but by “omission or commission”, society has to carry some of the weight instead of just pointing fingers at others.

“When you listen to their stories,” she explained, “and you sit down and break down who they were as children and where the failure was and how they ended up incarcerated at the age of 18, 19, 20 years old, for me I really start struggling with how easy it is for us as a culture, as a society, to wait to the end game and then say, ‘Alright, mistake, let’s lock him up and throw away the key and for the rest of their lives’, where it would have been, on some level, easier if we had started when these children were three or four years old and society was failing them in school and failing them in healthcare and failing them in the community, failing their families.

“There’s a chance we could have saved them at that point. We could have turned their lives around. But that becomes part of society’s ignoring and not being responsible and responding to issues of poverty or inner city violence or racism or whatever it is that is occurring. For some reason it’s easier for us to ignore, wait ’til the end and then lock these people up.”

‘No-one, even lawyers, likes to see a crime go unpunished’

The public and the media, quite rightly, always want a perpetrator to be identified and punished,” said Greg Curtain, a senior counsel solicitor in Sydney, Australia.2 When he compares how the justice system and media look at judgements, there can be an over-dramatising or over-simplifying that creates an image of judges being “soft on crime”.

The justice system deals with events objectively in a way that non-lawyers might not fully understand, and so it fails to meet a public emotional response, he said.

“Unfortunately,” he explained, “not every perpetrator is caught, or proved to be guilty, because the criminal justice system requires proof beyond reasonable doubt (preferring some perpetrators to go free rather than some innocent people being punished if a lower standard of proof was required).

“No-one, even lawyers, likes to see a crime go unpunished, but it is unsatisfying on an emotional, human level. Thus, when the public/media see a trial for a horrendous crime, and yet the accused be judged “not guilty” (and there being no other suspect) there can be an unsatisfying reaction to the criminal justice system as it is (wrongly) perceived to be allowing a perpetrator go free, or a convicted accused too lightly punished (in the eyes of the public/media).

“This arises, at least partly, because the public does not see and hear all of the evidence, and the media is complicit in that it doesn’t report all of the evidence (particularly that which favours the accused).”

Return to Part 1 – ‘Find out who is to blame’

In the cases of the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York, where grand juries decided not to seek indictments against white police officers, and similarly the podcast Serial about a possibly wrongful conviction of Adnan Syed,3 society says that the court answered the question of guilt incorrectly – “the law is an ass, as it were”, explains Barbara Fried, William W. and Gertrude H. Saunders Professor of Law at Stanford University.4

“Obviously there’s anger about wider societal injustices of which this is just a small part. But the triggering event and the core of it is the law got the law wrong,” she said.

Prof Fried said a central problem is not that the public can’t understand complex arguments or events, but that they must rely on intermediaries to process and present all the relevant information. She used the example of the early debate over what was dubbed Obamacare and the Republican charge that “death panels” would be set up for “grandma”, where politicians don’t feel they can take nuanced views of moral responsibility and instead reduce the debate to either-or and us-them arguments. And while for their part the media don’t ask the right questions, philosophers don’t deal with the realities of policy either.

She said: “A jury gets a lot of relevant facts; but if we’re talking about policy determinations, like incarceration, the average citizen, indeed almost all citizens, lack relevant facts to make a judgement that would be common sensical from their own standpoint.

“And therefore they are held hostage to intermediaries who frame these issues, whether it’s the press or philosophers or politicians. All three groups have not done as responsible a job as they could have in guiding people’s intuitive responses in these situations.

[Tweet “‘They are held hostage to intermediaries, whether it’s the press or philosophers or politicians.'”]”We’ve got politicians on one hand, in this country at least, who over the last three, four decades, have reduced the whole issue of crime to a soundbite – ‘You’re either for us or you’re against us’ – and tied it to a kind of atavistic response, that ‘You did the crime, you do the time’.

“And the question is, who’s going to save people from that simplistic version of what they’re getting from political discourse? I think the media has an incredibly important role to play in this, but generally doesn’t play it. Generally it just feeds the flames of political rhetoric. Is it impossible? Is it intractable? I don’t think so – I really don’t. But maybe I’m wildly optimistic here.”

She added: “If I would hope for anything from the intermediaries who are going to translate all of these issues for the general public, it would be to focus not just on the story right in front of them, but to get them to think seriously about what the consequences would be of acting differently.”

The moral question of blame

In an example used by Prof Fried,5 there is an example of a bus driver who hits a child who darted in front of the vehicle. There was nothing the driver could have done differently. But are they still morally responsible for the death?

The philosophical concept of “moral luck” says that they are. But the counter argument is that otherwise nobody would be held responsible for any actions because there were factors beyond their control.

“If the answer is, ‘We think they should do exactly what they did’, then I do not understand what people mean when they say they are nonetheless morally responsible for having done it, unless it is just a statement of, ‘We’re still mad at them. The bus driver ran over a kid, we’re still mad at them.'” said Prof Fried.

“Maybe it’s a powerful emotional response we have, but what is its moral content? How is it morally defensible that we’re mad at people for doing things that we would not have wanted them to do otherwise when they did them.

“There are many good reasons to hold people accountable in one form or another for having murdered somebody, whether we think they are morally responsible for them in a strong sense, but the reasons are all utilitarian, both to specific deterrents by incapacitating people who we think are very dangerous, general deterrents, rehabilitations [and] a number of other motivations.”

Prof Fried said that the law takes a more limited interest in questions of whether someone is morally responsible for a crime. “Blame” isn’t separate from responsibility for a “bad act”.

“Questions of blame underlie the structure of the law,” she explained. “But it’s concerned about whether someone acted wrongfully, and if so, what sorts of punishment are appropriate. Wrongfully has two meanings built into it, or two possible implications.

“Is the act itself one that we wish the person would not have done? Is it transgressive of values we hold dear? And the second is, was the person morally wrong in doing what they did?

“In law, holding somebody responsible can be a synonym for convicting them or, if it’s a civil suit, finding that they’re libel to pay a judgement to the other side. That’s just a statement of the outcome of the case and nothing more.

“We could go further and say, ‘We’re holding you responsible for these actions’, that is, ‘The reason we’re convicting you is because we think you were morally responsible for doing the actions that you did’ and we might generally assume that actions are deliberately taken, etc. And so the finding of moral responsibility follows directly from – in the criminal code at least – a conviction.

“But we sometimes pull them apart and talk about the concept of moral responsibility as blame separately in the law. I think that outside of the law, these terms are never used with precision and it makes it very hard to get a hold of the arguments.”

Prof Fried said the law and legal language has not sufficiently influenced society and philosophy to give clearer definitions about holding somebody accountable for what they did or what happened. Is the person responsible? Should they bare the consequences of their actions, and how?

“I actually think that one lesson that philosophy has to learn from law, or at least an example it might follow, is to try to think about statements like, ‘He’s morally responsible’ in operational terms,” she explained.

“What are we really saying when we say that? What do we expect of him? What are we going to do to him? Be it just blame him at one extreme, throw him to prison for his life at the other extreme? What are the consequences of saying somebody is morally responsible or blameworthy for their actions?”

In the concept of “soft determinism”, explained Prof Fried, saying someone is morally responsible means they are responsible because they could have done otherwise. There are situations where someone might be incapacitated or it would be otherwise impossible for them to have acted differently. And as more is learned about how genetics and upbringing affects individuals, that will further complicate the debate.

“If your instinct is a want to punish people for doing bad things,” she said, “then I think it’s indefensible to do that unless you think in some meaningful sense, they could have done other than they did.

“There’s a long philosophical tradition called compatibilism, which essentially holds otherwise. And it’s the dominant view in philosophy now and I think is, by default the dominant view in society: if you did something you shouldn’t have done, people’s first reaction might be to think, ‘you could have done otherwise’ .

“If you’re going to face up to facts, the reality of the limits on all of our capacity to direct our own lives and our own actions, I think you have to approach the question of blame with skepticism about whether it’s appropriate to assume that people who act wrongly actually had the capacity to do otherwise in a robust, meaningful sense.

“If I would hope anything changes in people’s responses, it would be to say, ‘Okay, what would I have done in this person’s shoes if I were really in their shoes? Could I have controlled my anger? Would I have realistically known about this and that risk? What do we know about people who were brought up in the way this person was brought up? How many people in that situation actually act otherwise when presented these kinds of provocations? How many people’s biological make-up precludes the kinds of responses we would expect of them?

“I think coming at that question with healthy empirical skepticism would be a really good thing and would tone down the kind of cheap moralism that infects a lot of areas of public policy and get people to think more realistically about what we can expect from each other and how we can help produce it in people who really don’t seem very capable of doing the right thing right now.”

You started it! No you!

From media to public to lawyers, from public to media to lawyers, from the law to the public to the media – is it a closed circle without escape?

“I think that’s a really interesting question,” said Jennifer Thompson. “When you look at Ferguson right now, the people want someone to be held accountable. The media comes to that and says, ‘Gosh, this creates a really great media story’ and I think it does follow each other.

“The media plays on, whether you want to call it a witch-hunt, this human need to draw and quarter somebody and it just makes us feel better at the end of the day if we can blame. Because then it takes the responsibility of our our shoulders.

“And this is what I talk about a lot: the responsibility can either be by omission or commission. Whether it’s because voters voted in the wrong district attorney or because voters didn’t let their voices be heard and they didn’t go out and vote. . . there’s all different kinds of human nature issues when we look at this.

“Which came first the chicken or the egg? Does the media incite the community or does the community incite media to come and create some huge story? I don’t know what’s first.”

Dr Jacqui Ewart, of Griffith University’s school of humanities and members of the Key Centre for Ethics, Law, Justice and Governance.

Dr Jacqui Ewart at Griffith University said sometimes media do follow the “noisy voices” tweeting about a subject, rather than those sitting quietly at home.

“People who are more rational and level in their discussion and debate won’t be going on Twitter to be a noisy voice,” she said. “So it’s things that aren’t being said that are just as important as the things that are being said, and I think journalists forget that.

“Sometimes it will be an agenda that a particular news media organisation has, and we’ve certainly seen that in recent months in Australia.

“You can’t really say it’s the chicken or the egg – sometimes it’s the chicken and sometimes it’s the egg that came first.”

Ms Thompson said the media can do a very poor job, particularly on criminal justice, crying out “Why’d you do it?” to the person in court in handcuffs and an orange jump suit. And the television audience automatically think, “Well gosh, they’ve arrested him, he must be guilty.”

But one particular problem with blame, of an individual or perhaps an entire district attorney’s office, is to force one or many people into self-protection mode, she said. It’s natural to defend yourself.

Since Ronald Cotton was exonerated, the media has sometimes referred to Ms Thompson as “the victim who falsely identified” the man responsible, implying it was in some way malicious. Would someone step forward to admit a mistake if they knew they would get blamed?

“Responsibility is different,” said Ms Thompson. “If a person feels that they can be truthful and transparent and they’re not going to be bludgeoned and drawn and quartered and burned at the stake, then it creates a safer and more secure environment for a person to come forward and say, ‘This is where we might have failed, this is where the investigation probably went in the wrong direction, this is something we didn’t have the information at the time or the training at the time but we now realise this is a potential problem. Let’s uncover it, let’s be honest and then let’s learn from it and be better for it’.

“But blame I really think does create this place where we got to go hide out.

“And honestly that’s one of the reasons you will not find many victims and survivors and family members from wrongful convictions doing the work. Because why would you? If you’re going to come forward and. . . people in general, the community, want to burn you in effigy? Why would you ever come forward?

[Tweet “‘If people want to burn you in effigy? Why would you ever come forward?'”]”Knowing what I know now as a survivor of a violent crime and a wrongful conviction, knowing the things that I have had to go up against, I don’t know that I would do it again.

“Because I’ve had death threats, I’ve had people say the most egregious things you can possibly imagine to me, who was almost killed? I was brutally raped and then almost killed? Because I had the audacity of being a human being and making a mistake in my memory and a series of events took place that would encourage me to pick the wrong person out of a line-up because the actual culprit was never there, because I had the audacity of being a human being. And then to come forward and say ‘I’m sorry’. And then to go beyond that and say, ‘Gosh, is there something I can do to help educate and inform about how the memory works and the mistake I made so perhaps other cases across the country can be uncovered and innocent people can be released.

“Because I had the audacity to come forward and be honest. You can not imagine the things that have been said to me.”

But transparency alone won’t solve the cycle of blame, replied Prof Fried, because the public would still rely on intermediaries such as the media and politicians. She gave the example of the process in litigation of one or both parties releasing millions of pages of “relevant” documents in a bid to deter opposing lawyers going through everything.

“The same thing is true with the government,” she said. “Complete transparency about all facts will be useless to people. We need some kind of responsible filter for figuring out what facts are important to communicate to people. It comes back to intermediaries: responsible politicians, responsible press, responsible pundits, responsible academics. We are all the intermediaries in those very, very important ways for people.”

Pointing fingers at human beings

When the public is presented with flawed stories or arguments from those intermediaries, it becomes difficult to imagine walking in someone else’s shoes, imagining one’s own actions in similar situations.

Albie Sachs, former justice of the South Africa Constitutional Court, at a symposium at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Glasgow, Scotland. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Albie Sachs, anti-apartheid fighter and former justice of the South Africa Constitutional Court, wondered if the movement he belonged to might have overdone blaming the system alone. But he still considered it better in the long run, “a more fruitful way of making the world better and reducing the amount of cruelty and inhumanity in the world than simply going for people who’ve been responsible for the cruelty”.

Changing culture, values and the way things are done was part of Mr Sachs’ work as a judge.

“In traditional African jurisprudence,” he said, “the idea of restoring the ruptured community, of reintegrating the offender into society is very pronounced. So whole families get involved. To my mind, that’s potentially far more powerful and enriching than advocating, attributing blame to an individual who then gets, in the worst cases, killed, in other cases segregated, locked up.

“Apology plays a bigger role. Things of practical reparation play a bigger role. But of course that came after a finding of guilty based on the normal due process of law, evidential principles. “

“Behind every single one of those stories is a human being. And a family. And there’s loss,” concluded Jennifer Thompson.

“And I think that’s something that we just seem to have forgotten. Behind every single one of those cases, there’s a mother. There’s stories and we don’t seem to want to gather the stories and understand the human beings that are behind them and why they made the decisions they did or why they are where they are.

“We’ve lost that. We really have.”

CORE PRINCIPLES APPLIED

No relevant issues on principles 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9 or 10.

1. Freedom of expression: Published research papers are a matter of public interest and should be reported as such.

3. Independence and accountability, and 6. A duty to openness (jointly under both principles): Reporter Tristan Stewart-Robertson has previously sold freelance stories to and been published by News International papers in the UK, the British arm of News Corp Australia, publishers of The Australian and the Courier-Mail, the two newspapers subject to the research. Tomorrow checked with both researchers on any previous work. Dr Ewart said she had not worked for News Corp Australia in the past. Dr McLean said he had worked for the Daily Sun from 1986 to 1990 when it was owned by Rupert Murdoch, chairman of News Corp. Tristan is also a shift reporter for the Scotsman newspaper.

11. Promote responsible debate and mediation: How do you attribute blame in your life? Do you feel you do so fairly? Would your take be different if you were presented with different or better information by the media and others?

- The book, and further articles about the case from PBS, the Innocence Project and past interviews. ↩

- Greg Curtain SC, Level 22 chambers. ↩

- The New York Times has all the documents considered by the grand jury in the Michael Brown case and a limited release of details is available in the Eric Garner case. All episodes of Serial can be found at http://serialpodcast.org/ ↩

- Stanford University departmental profile. ↩

- This example was used in a Boston Review 2013 feature and responses on the subject of blame. ↩