“Fight” – or – Tempestuous Teenaged Canada

“Fight.” It’s the single-word answer by Nik Nanos when recalling the Charlottetown Accord.

A member of the PC Party at the time, he was “volunteered” to lead the campaign in Kingston and the Islands, simultaneous with Liberal MP Peter Milliken’s own committee1.

“It was actually a pretty clear fight,” he says, “much more of a fight than in a number of other places because there was actually more of an organised group against the Charlottetown Accord – the Alliance for the Preservation of English Canada.2”

In Ottawa, Rabbi Reuven P Bulka’s first memory from the campaign was the public reaction in a “packed” meeting in Tudor Hall3 on the accord.

“To hear some of the venom, I was really surprised,” says Rabbi Bulka, who co-chaired the Ottawa South YES Committee with then local Liberal MP and later deputy prime minister John Manley.

“There was really some strong anti-French feeling. It was surprising, stunning. It was not just one person. This was supposed to be a rally for the yes side. This was a wake-up call that there was a lot of work to do.

“I always have a difficult time rationalising stupidity. It was just emotive sloganeering – it was yelling and screaming, not rational discourse.

“On facts you can argue – on emotions, you’re stultified.”

Rabbi Bulka had previously formed “Clergy for a United Canada” and collected 30,000 signatures from clergy to present to the prime minister. So he has no regrets about agreeing to fight for the yes side.

“I probably would have hated myself for the rest of my life if I had not done it,” he concludes. “If there’s a calling to help your country, you do it. I’m not sorry I did it; I’m sorry about some of the things I heard that day.”

On the east coast, Beryl A MacDonald was hearing rumblings far predating Charlottetown negotiations. Today a Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge in the family division, in 1992 she led the Canada Committee in Cumberland-Colchester after “active” work with the Liberal Party.

Justice MacDonald says Cumberland-Colchester was a very conservative riding and “a lot of people were not particularly friendly towards Francophones”, some of the attitudes harkening back to the second world war when Quebec voters opposed conscription in Canada’s then second national referendum4.

“People on the committee focused on that a lot to try to bring the community around,” she says. “We felt we had a really uphill battle.”

In neighbouring PEI, Lynn Murray was co-chair of the Prince Edward Island YES Canada Committee with the hockey star Orin Carver5. She is now a QC at the firm of Matheson & Murray in Charlottetown6.

She says the island campaign was “pretty well organised”, but bi-weekly conference calls to other parts of the country started to give a flavour of the problems starting to confront the yes forces.

“We never ever thought for a minute that the Charlottetown Accord would not pass in PEI,” she says, adding that the campaign was a “fabulous experience”, though “disheartening” to be on the phone with other regions.

[Tweet “””We never ever thought for a minute that the Charlottetown Accord would not pass in PEI.””]Premier Gary Filmon in Manitoba was hearing the same reports as gatherings took place across the west, yes campaigns trying to support each other against the no tide.

Deborah Coyne says putting together a no committee “didn’t take much” after all the work against the Meech Lake Accord over the previous years.

“Sure we felt like underdogs,” she says, “but I had good instincts, and based on my experience during ’87 to ’90 and the hundreds of correspondence and speeches, I knew Charlottetown hadn’t changed Meech enough to make it acceptable to people.”

Robbie Shaw was fighting more than a no side in Nova Scotia – he was fighting relative apathy. Mr Shaw co-chaired the provincial Canada Committee in Nova Scotia, stepping up from his position as president of Clayton Developments Limited. He is currently executive advisor to the dean of management at Dalhousie University7.

The campaign was “phenomenal”, but a “hard slog”, he says. “People weren’t passionately interested and there was all kinds of scepticism, so that made it more difficult.

“The people who were coming out [to meetings] were the 5 or 10 per cent who have a natural interest in public policy and government. The broad population were not passionately interested. And in some sense, why would they be?

“I agreed to undertake that responsibility because I thought it was important. I did not think it was a slam dunk at all. I did think there was a reasonable chance to getting more than 50 per cent. And it turned out in Nova Scotia we got 48.8 [per cent] – it couldn’t have been much closer.”

Monolithic parties

Mr Shaw was a prominent Liberal in 1992, but his sister, Alexa McDonough, was leader of the Nova Scotia New Democratic Party, later it’s federal leader. He jokes, “that’s my major claim to fame”, but it is also an example of the co-operation that crossed party lines – for both the yes and no sides.

Lynn Murray in PEI says the campaign brought together “all walks of life” and Justice MacDonald describes the events of 1992 as “one moment of high political activism”.

Peter Milliken in Ontario says he thought that shared backing was “useful, where in an election you know these people are going to be on the other side, at least quietly if not enthusiastically”.

Why did people join forces? Andrew Nellestyn says it was his “consuming interest” in ensuring the country stay together.

“To me it doesn’t really matter whether you’re a Liberal or a Conservative who expresses concern about the break-up of the country,” he asserts. “I’ll help either one, or both.”

Nik Nanos, having analysed public opinion for decades, can recognise political parties “are not monoliths” of universal support for leaders or policies.

“I think that was the case in this instance,” he says, “that there were individuals from all stripes that had concerns about the Charlottetown Accord.

“In the case of Kingston and the Islands, the leadership of the main parties agreed to cooperate and were on the same page. And for those who were not on board, I think they basically took a low profile as opposed to being actively against the local Liberal MP or the Conservative organisation that were formally and actively supporting the Charlottetown Accord.

“It’s a little different because there was less of a partisan atmosphere compared to other ridings. And as a result, the mere fact the yes campaign offered to get out the vote for anyone to make sure that as many people in the riding voted as possible, actually helped build a lot of good will for the yes forces.”

Alex Cullen, currently parliamentary assistant for York South-Weston MP Mike Sullivan, says the debate “crossed party lines, cross demographic lines, and allowed for ordinary people to speak out about what the political elites were doing to their country”.

That sense of a separation from leaders or “elites” is echoed by Deborah Coyne, who found it exciting.

“You talk to hard-core Liberals, like me,” she says, “and they felt off-side because all the national leaders supported it. It was a very exhilarating time because those of us who joined together were NDP, Conservative and Liberal and it was outside the party, and it was really nice to be in a debate about substance and about the country.”

For all the cooperation on local and provincial campaigns, and with national leaders of different stripes touring the country, then chief electoral officer Jean-Pierre Kingsley saw a very different picture. Cooperation was the exception, rather than the rule, because there was a federal election that had to be called within the year.

“There was also a sub group of exceedingly senior political operatives and I met with them several times,” says the former chief electoral officer. “And they were conscious of the fact that soon after the referendum, they would be after one another.

“This became clear in the way that they were talking to me. And I kind of got the impression that they were not cooperating as much in terms of getting out the vote, sharing their lists of supporters.

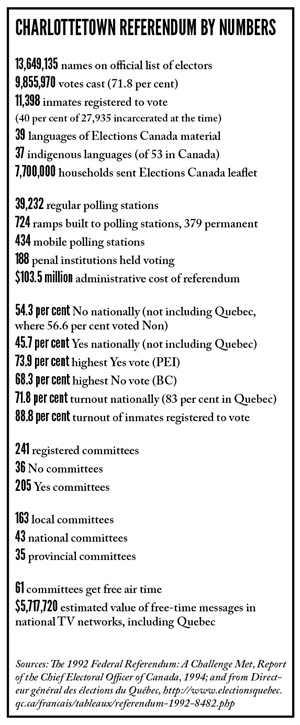

“I did not get the impression that they were cooperating in operational terms with one another. In terms of messages, perhaps. But not in terms of getting out the vote. And a 2 or 3 per cent turnout difference possibly could have made a big difference in the referendum as you see from the numbers.”8

Campaigns, forklifts and 1am

Speeches to women’s institutes, public rallies, offices and debates – both formal and otherwise – filled the weeks leading up to October 26. Robbie Shaw recounts giving two talks a day through the period, while Gary Filmon remembers provincial leaders sharing the stage to try and bolster the yes side.

Peter Milliken says the campaign was something you worked on when you had a moment.

“It wasn’t something you were going at morning, noon and night,” says the retired MP. “I don’t recall spending a lot of time discussing this at the door – you go and urge people to get out and vote and urge them to vote yes.

“Going door to door here was useful just to have people see you because you are the MP and you want to get re-elected and all that sort of stuff.”

“I’d say, ‘Well, we’ve got signs coming, how are we going to get the signs up?’,” says Peggy Gallant. “So we’d have a little meeting down in my front room at my home and they’d say, ‘Well I know John and Joe and Jack and they’ve put signs up for me during my campaign’.

“I remember going into homes, retirement homes for elderly and man, those people love politics and they talk politics all the time and they’re really interested.”

Also in Nova Scotia, Justice MacDonald recalls late nights and good will from the community. When print materials arrived by train, a local business person arranged for the use of a forklift, at no cost, to help unload them. The campaign needed to bring people around and change some attitudes towards Quebec.

“We talked and talked and strategised and had meetings through this campaign – there were many 1am evenings trying to work out our approach,” she says.

The perception of Quebec coloured much of the debate around the Charlottetown Accord, just as with Meech Lake before it.

But there was also fear, particularly for some in the Maritime region that if Quebec left Canada, that the eastern provinces would be cut off.

“A lot of people resented Quebec,” continues Justice MacDonald, “because they believed that province was favoured over and above the others. Certainly there were some reasons for people to have developed that perception.”

Andrew Nellestyn says anything that threatens the unity of the country “needs to be addressed. . . in other words, that Quebec is kept in confederation”.

But the desire to keep Quebec also drove some of the opposition to the accord.

Preston Manning says Albertans saw the federal government falling over themselves to accommodate the province by recognising them as a distinct society.

“When the west argued for senate reform as a more effective way to approach regional representation or fiscal responsibility or things like that, there was nowhere near the rapid and thorough response,” says Mr Manning.

“I think there was a sense that other people’s constitutional concerns were higher on the agenda, and that the people who threatened separation in order to get their way got more attention than people who tried to take a positive, constructive approach through the existing political institutions.

“Albertans weren’t stupid – they knew it was mainly motivated by trying to satisfy Quebec’s aspirations and then throw in enough other things to try and bring the rest of the country along.”

[Tweet “”Albertans weren’t stupid – they knew it was mainly motivated by trying to satisfy Quebec’s aspirations””]Deborah Coyne insists the opposition was not an “anti-Quebec thing”. But the distinct society clause was still the problem, undermining the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

“The clause that they had in there dealing with Quebec was an interpretive clause that would have an impact on the division of powers,” she says. “Opinion was divided on that and it was something we were doing that would be in the constitution for a long time. So I just remember looking at it and thinking, ‘No, they still haven’t got it right and this is going to be a controversial document’.

“[The campaign] was a citizen-based opposition that just didn’t feel that you should be really changing the fundamental structure of the federation in such a comprehensive way.”

Prime ministers and personality

There were prime ministers aplenty during the referendum campaign – four, significantly. Joe Clark, as minister of constitutional affairs, was as involved in Charlottetown as Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, and campaigned for the accord along with Mr Mulroney’s successor, Jean Chrétien.

Former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s opposition to the accord, in speeches and articles, had an effect on people. For those who still admired the political heavyweight, his views mattered.

Deborah Coyne, whose no campaign was centred on the same principles of protecting the charter, agrees Mr Trudeau’s intervention “galvanised people”, but that that alone could not have fed opposition that wasn’t already there.

“Mr Trudeau[‘s intervention] was a factor,” says Robbie Shaw. “Even though I disagreed with him and even though I was considered to be a big Liberal, it did sway certainly the media. And I think that stopped some of the positive momentum for the change. Was that alone the reason why it wasn’t successful? I don’t think so, but it was a factor.”

Another issue was the growing unpopularity of Mr Mulroney himself. Though he would step down just months after the defeat of the accord, it was not enough to save his party from the near total wipe out in the 1993 election.

Mr Shaw says: “The prime minister was seen as a bit of a smarmy salesman and not loved by a huge percentage of the population.

“I think it’s unfair because the prime minister in fact a) understood the issues incredibly well, b) I think was very genuine in feeling that this was important to try and accomplish, and c) had the confidence of most of the premiers. But he had a bit of an image problem and I don’t think that helped.”

Peggy Gallant agrees: “I think Mulroney had a big vision and I think he was just slaughtered for it. Plus he was becoming quite unpopular and I think, when he was doing his own campaigning for the yes campaign, I think he was kind of using a bit of a threatening approach – ‘If you don’t sign this, if you don’t vote yes, Canada’s going to fall apart’.

“Canada didn’t fall apart. We’re still here. You can’t threaten people.”

Preston Manning, looking back, both compliments and critiques his competitor for conservative voters.

“I do think Mr Mulroney got carried away,” he says. “What he really wanted to do was sort of trump Mr Trudeau with whom he was always competing, even though not directly, on constitution making. There was sort of mixed motives.

“But it was an extremely difficult thing to do under the best of circumstances to have a broad constitutional agreement covering so many subjects that would carry the judgement of the public.”

The river of information

Different political leaders, competing visions and gut reactions were all factors in the defeat of the Charlottetown Accord. But the voices articulating the pros and cons of the accord were only heard thanks to handing the speakers a free megaphone.

The referendum was made possible by the Referendum Act9, passed just months before the vote. Jean-Pierre Kingsley at Elections Canada brought in the registration of third-party referendum committees and an offer of free broadcast air time to those who wanted it.

The referendum was made possible by the Referendum Act9, passed just months before the vote. Jean-Pierre Kingsley at Elections Canada brought in the registration of third-party referendum committees and an offer of free broadcast air time to those who wanted it.

“Referendum committees became the model for the third-party regime that was eventually passed into law for elections,” says Mr Kingsley. “The rapid registration during the referendum period, the reporting of expenditures, and other features were all used to prove the system could be applied to elections.

“One of the characteristics of the Canadian system is you have limits on spending and parties. The whole third-party regime is essential and the demonstration was made at the referendum that a scheme like that could work, and did work.

“It had been a main issue in the 1988 election with a lot of private sector companies pushing a lot of money into the campaign.

“And Canada recognises freedom of expression, but we also know that if someone is screaming – which is the equivalent of being able to spend untold millions – that’s no longer free speech. I mean, how do you get your voice above someone who’s screaming at you?”

With limits came the offer of air time, signing up broadcasters to hand over the equivalent of almost $6 million of ad slots10.

“It is THE feature that allowed the no camp to effectively take over in terms of public opinion,” declares Mr Kingsley. “Their ads were very effective.

“There’s a natural base there, because people are scared of change or reluctant to change. And they were able to capitalise on that through the free advertising.

“It was the free time feature that I always considered to be THE big thing of that election. In terms of impact on the whole system, you got [third parties] to register, but at the same time they were given something great, which is free time.

“Now, the yes side had as much claim to it but obviously they were not as successful. The polls indicated that at the start, the yes camp was going to win. And, one follows the polls during the referendum campaign itself, the 36 days, and bang, you see it changing over time.

“I remember the yes side, the positive ads were Canada geese flying into the sunset. . . you can only get so many people to relate to Canada geese flying into the sunset.

“People were criticising the yes side ads for being that kind of mushy appeal to, well, nationalism I guess. Whereby the no side was hitting the different segments of the deal. They could pick one out and tear it to shreds.”

[Tweet “”There’s a natural base there, because people are scared of change or reluctant to change.””]The biggest benefactor for time from the no side was the Reform Party, led by Preston Manning11.

But Mr Manning says air time was not much help because of “almost unlimited resources” for the yes campaign. Their strength, was grassroots.

Just as Mr Kingsley points out, Mr Manning identifies the flaw of an agreement such as the Charlottetown Accord.

“One of the difficulties of those blanket accords covering many aspects is that people will cherry pick some parts that they’re really keen on and they’ll find other parts that are totally flawed,” he says. “They’ll really make judgement on the basis of whether their particular favourite part was advocated and framed strongly enough. Or they’ll decide to be against it because they don’t like one particularly element.”

The other main no committee, Deborah Coyne’s Canada for All Canadians group, got a loan of money from Manitoba-based media mogul Izzy Asper12 to do their ads, she recounts. But when they didn’t use up all the time they were entitled to, the group forfeited the $500 deposit.

“It’s kind of bizarre – you forfeit it when you don’t advertise enough,” she says. “Of course we were the underdog. But the nice thing about a referendum is it’s extremely levelling.”

The Reform campaign distributed more than 1.5 million copies of a 13,000-word broadsheet paper that included the entire accord, commentary and circled sections to highlight for the public.

“We were laughed to scorn when it first came out,” says Mr Manning, “because our opponents said, ‘Well you will never get ordinary busy folks to read anything like that, let alone something like that that was written in legalise.

“But we found a large, large number of people studied the accord themselves, and they respected the fact that somebody thought they had the intelligence and ability to do so.

“They understood a lot more than the people gave them credit for, certainly that the other side give them credit for. And that kind of communication went over far better than the slick type of advertising, both electronic and print wise, done by the yes side.”

For Mr Manning, the campaign was able to turn the tide by providing voters with information. He quotes Thomas Jefferson, who wrote in 1820: “I know of no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them but to inform their discretion by education.”13

“Our whole campaign in Charlottetown was to try to inform the discretion,” says Mr Manning. “And that in itself is an interesting phrase. [Jefferson] didn’t say just try to persuade them to support your view, inform their discretion, inform their ability to make a choice and trust them to make that choice, rather than just telling them what to do. That was kind of our motto going into that campaign.

“We had this ‘know more’. . . if you knew more about this thing, you would not be in favour. We didn’t try to tell people in a very strong way to vote against it. We just said, ‘Here’s a copy of this thing, you read it. We’ve circled the parts that we think are worrisome but you read it, you study it, you talk about it with your friends and come to a judgement about and then get out and vote on the thing’.

“Don’t underestimate the capacity of ordinary voters or the public to become interested in an issue and to become informed on it and to make a wise decision. They don’t always make a wise decision, but I think the democratic lesson from Charlottetown is the most important one – more so than any, say, legal lesson in the narrower constitutional sense.”

He adds: “It strengthened my conviction that ordinary folks, faced with all the challenges they’ve got, of holding down their job, and paying a mortgage, and getting their kids to school, that if you can get them the information and give them time, that they can come to informed decisions on some of these big issues. It really re-enforced my view that democracy is a pretty good system, even with all its flaws.”

Democracy and information to the voters worked for the yes side too, according to Nik Nanos. Despite a well-organised local no campaign “rallying anti-accommodation and anti-French sentiment”, the “number one” request to the campaign office was for a copy of the accord.

“Canadians were interested in actually reading the legal text,” he says. “You don’t get that very often. And I think the key take away is that if you put more information in the hands of voters, and if you give them the opportunity to vote, even if you’re unsure as to whether they’ll support your cause or not, that that’s always the best path forward.

“We were told that we were putting out more information related to the Charlottetown Accord than many of the other ridings.”

Justice MacDonald noticed the same desire “once kindled, to learn, to be engaged, to try to understand”.

Both Mr Manning and Alex Cullen, on distinctly separate sides of the political spectrum, viewed the no campaign’s ultimate victory as one for “the ordinary person” against “political elites”. Given a copy of that “elite” constitutional document, the people rejected it, in some parts of Canada at least.

But Peggy Gallant in Nova Scotia, looking back, recognises that the information was also too complicated, that too many issues were being addressed in one document.

Eternal internal resistance to change?

So, 20 years on, how do the original campaigners interpret the results? Are different parts of Canada so different that they could look at the same document and arrive at opposite conclusions?

Nationally, Preston Manning sees both a Canadian tendency, and a regional one.

“Maybe it’s sort of a sad lesson and I’ve noticed this not just in reference to Charlottetown but to other measures,” he says. “Unfortunately, for one reason or another, I think Canadians are easier to rally against something than they are for something.

“Far more often, Reform’s been on the side of trying to get people to adopt what we consider some positive reform: budget balancing, senate reform, criminal justice reform, democratic reforms. And it does seem more difficult to rally Canadians to support a new initiative than it does to get them to oppose one. I think that’s a negative thing. I think it’s got something to do with our national character.

“Canadians – and you’ve got to be careful about generalising because this varies from different parts of the country – if you present a new idea to many Canadian audiences, the initial reaction, and certainly [in] the media, is to give you 100 reasons why it won’t work, can’t work, probably shouldn’t be considered.

“In other words, the initial reaction is a wet blanket syndrome and then, if you persist at it, Canadians will start to warm up to it. They’ll have this second thought, ‘Well maybe, it’s not quite as bad as we thought – that might be good’.

“Whereas there are certain jurisdictions – like in the US you think of California or Texas; in Canada, Alberta, southern Alberta and particularly Calgary – where the initial reaction to new ideas is, ‘By golly, you know that might just work’. It’s a sort of positive thing and then they have the second thought, ‘But we better analyse this’.

“And the difference that makes if you’re the promoter of the innovation or reform, is when the first reaction is the wet blanket, you almost despair that you’re not going to get anywhere and you may give up, or in the entrepreneurial world you go south to the United States.

“But if initial reaction is positive and then there’s sober second thought and questioning afterwards, it makes all the difference to the entrepreneur or the promoter of the idea and gives them some encouragement to go forward.”

He adds: “This is something far more general than the Charlottetown Accord. In that particular case we were campaigning against something which was an easier campaign to conduct than when we were advocating big reforms ourselves.”

And in the west, Reform and the no side won.

Small victories and big defeats

Both sides had their victories, with local yes campaigns drawing comfort from winning their battles, even if the large revolution was fruitless.

In Kingston and the Islands, both Peter Milliken and Nik Nanos recall getting out the vote as a key factor.

“In terms of the local campaign,” says Mr Nanos, “one of the things that the local yes campaign benefited from was the series of mistakes that the no campaign made. One of the mistakes that they made was that they had raised money for television ads. But they had looked at broadcasting the ads, in order to save money, from a station in the United States, which is in contravention to the Elections Act where you’re not allowed to use any foreign broadcasters.

“One of the decisions we made was to get out the vote for anybody, and to not be obtrusive in terms of their voting intentions. And I think that garnered a lot of good will among local voters because it showed a certain level of respect. And it was kind of unusual.

“I think that’s what tipped the balance in terms of the performance compared to many of the ridings in the surrounding area. We were able to trump the national trend at least.”

On PEI, Lynn Murray still recalls premier Joe Ghiz, the salesman, his ability to command a room, and ultimately make the home of confederation and the Charlottetown Accord deliver the highest yes vote in the country, at 73.9 per cent.

“Joe could get in front of any group and he could persuade you to his way of view,” she says. “He could energise the room such that you could hear a pin drop.”

But Mr Ghiz, in his speech to the island’s Hillsborough Rotary Club, foretold what would happen weeks later on polling day: “Let not the prophets of perfection become the enemies of the good.”

Unknowingly, Mr Filmon uses the same words as Mr Ghiz, 20 years on.

“In retrospect, it was a very, very bitter and sad lesson for me to realise that when you have something as complex, and so many different elements to it and so many different issues to be looked at, that of course the perfect becomes the enemy of the good,” he says.

[Tweet “”In retrospect, it was a very, very bitter and sad lesson for me””]”We were certainly very disappointed, apprehensive as to what [the vote] might spur in Quebec.

“And then of course we got hit by the very deep recession that forced us all to really roll up our sleeves and try to get the economy back on track. So we almost couldn’t consume ourselves with thinking about the constitution. And that led to the rallying cries of, ‘Enough with the constitutional talks’. We’ve got serious issues on the economic front and we’re going to work on them because that’s what the public really want us to do. And that was kind of our way of putting it aside.”

Will Canada ever discuss the constitution again?

Part 3 – Is Canada too old to talk foundations?

- Mr Nanos led the Kingston and the Islands Canada Committee, and Mr Milliken led the Peter Milliken YES Committee. In the original report, committee names designate YES or NO, and Tomorrow has kept this formatting. ↩

- Not formally registered with Elections Canada for the campaign. ↩

- http://www.tudorhall.net/ ↩

- The first referendum was on conscription. ↩

- Details on Mr Carver from the sports hall of fame. ↩

- http://www.mathesonandmurray.com/lynn.html ↩

- Mr Shaw was appointed in 2011. ↩

- Ontario, on the western border of Quebec, could have been affected, with just 50.1 per cent voting yes; Nova Scotia might also have been influenced, with 51.2 per cent voting no. All other provinces had larger majorities on either side. ↩

- http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/R-4.7/index.html ↩

- See Elections Canada report, part 3. Download the PDF here: 1992_Referendum_Part_3_E ↩

- See note 10. ↩

- http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/asper/ ↩

- Thomas Jefferson to William C. Jarvis, 1820. ME 15:278 ↩