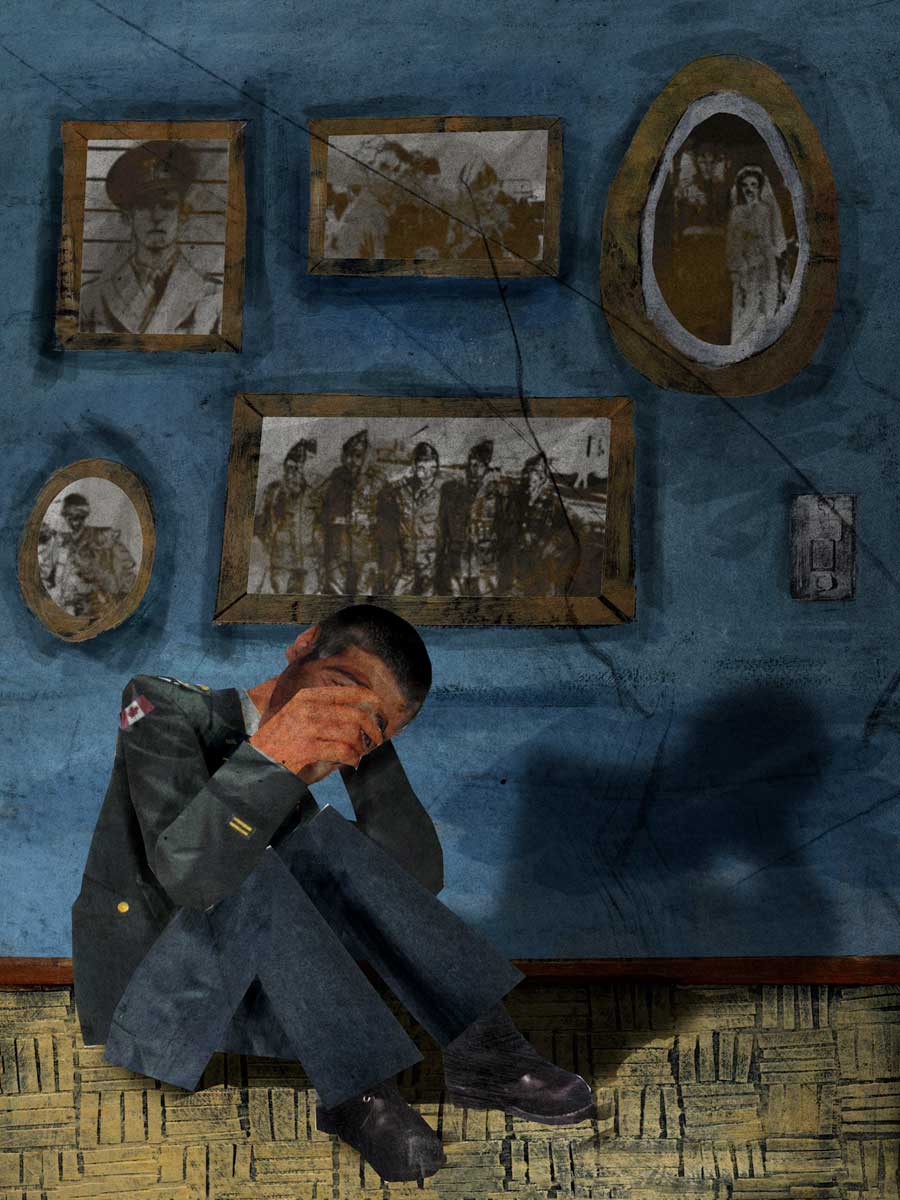

Armed service personnel and veterans are part of a family, but are the public and government supporting them? By Jason Skinner, Artist in Residence. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

This story includes the subject of suicide. If you need someone to speak to, please contact a support service in your area.

THERE are five standard news media images of military personnel and veterans: soldiers firing weapons; Remembrance Day services at cenotaphs in public squares; soldiers returning from Afghanistan, either welcomed by loved ones or in flag-draped coffins; yellow ribbons fluttering in the breeze; and more recently, the shattered families left behind after serving or former armed service personnel have taken their own lives.

Public understanding of the issue of support for veterans is confined to those visual records, and to whatever political reaction there is as the first response to all stories.

But the history of pensions, care and support in Canada, the competing internal arguments about how best to look after veterans and their families and the unspoken conflicting public demands for funds are all at play underneath. Is there a covenant or contract or duty to veterans?

The Canadian flag was lowered in Afghanistan on March 12, 20141 to signal the end of the 12 year mission in the country, leaving questions for decades to come about the actual effect on foreign soil and back home. A total of 158 soldiers lost their lives since deployment started in late 2001, as well as a diplomat, a journalist and two civilian contractors. More than 40,000 Canadians served in Afghanistan in that time.

At home, there have been 12 suicides reported by serving or recently retired Canadian since November 2013. While officials dispute statistics,2, the loss of life is not in question. The statistics on wider problems in the military and veteran community simply don’t exist.

“It is a crisis,” says Mike Blais of Canadian Veterans Advocacy.3 “People are getting divorced, families are being broken, terrible things are happening.

“Yes we hear about the deaths but we don’t hear about death by a thousand wounds prior to that final culmination. We don’t hear about the family discord. We don’t hear about how many times that woman has cried herself to sleep or huddled outside of the house terrified with their children until their husband came back to normal or the flashback ended or sanity prevailed. We have to make sure that these resources are there for these people.”

Since November 2013, there have been a number of high-profile reported deaths from suicide:

- Master Bombardier Travis Halmrast (November 25, 2013)

- Master Corporal William Elliott (November 26, 2013)

- Warrant Officer Michael Robert McNeil (November 27, 2013)

- Master Corporal Sylvain Lelievre (December 3, 2013)

- Retired Corporal Leona MacEachern (December 25, 2013)

- Corporal Adam Eckhardt (January 3, 2014)

- Corporal Camilo Sanhueza-Martinez (January 8, 2014)

- Lt-Col Stephane Beauchemin (January 16, 2014)

- Warrant Officer Martin Mercier (February 2014)

- Retired Sergeant Ronald Anderson (February 24, 2014)

- Master Corporal Tyson Washburn (March 15, 2014)

- Corporal Alain Lacasse, 43 (March 17, 2014)4

But suicide can be caused by any number of factors or circumstances, and the rate in the armed forces is lower than in the general Canadian populace, unlike in the US.

Veterans Affairs Canada, the federal government department that is responsible for soldiers after they finish their service, insists that help is available to veterans and families who are affected by PTSD, depression or “other operational stress injuries”.

Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

In a statement by email from the department,5 media relations officer Simon Forsyth said “case management” is a key part of their “frontline” service in developing a plan for the “needs and goals” of veterans and their families.

Veterans Affairs Canada has come in for criticism as it closed eight local offices6, though minister Julian Fantino7 has repeatedly insisted the government is committed to helping the armed forces and veterans.

Mike Blais is not convinced by government action, as proven by the need for his own organisation.

In a phone interview with Tomorrow, he says: “We base our activities on need and pain and suffering and there are so many who need, who are in pain, who are in suffering, and I’m talking about wives and husbands and children who are collateral damage from the Afghanistan war and deployments in the former Yugoslavia and the horror of genocide in Rwanda and Somalia and elsewhere.

“The obligation is there, and if we don’t step forward, if we don’t provide this help, the treatment, it’s inevitable: bad things are going to happen. It may not always end with death, at least immediately, it may take 20 years, a family destroyed and hatred for that person and alcoholism and all the horrors and the spiral of decay that happens when that wound is not treated and it infects the mind and runs free.

“I truly believe this government will not take effective measures until the people of this Canada start standing up for our troops, our wounded and the families of those who are standing by them and will have to stand by them for the rest of their lives.”

Army, Navy and Air Force Veterans in Canada (Anavets)8 agree there is not enough support from the government, but pin this particularly on money available during transition out of the armed services.

Dominion secretary-treasurer with Anavets Deanna Fimrite said with the military outsourcing of many of the services they once offered in-house, and the number of injuries from deployments, there is less flexibility for the armed forces.

She said: “If you cannot deploy, you cannot serve – can they change that?

“What Veterans Affairs needs to do is help these people transition out when they’re forced to do so.

“We are concerned if you’re medically released and have need to be retrained, there are programmes to help transition but while they are in that, they are being paid about 75 per cent [of their pre-release salary]9. That’s not enough to help transition.

“If you live on base, you have tremendous amount of support and are then moving to an area [where it’s] every man for themselves. It’s a really stressful time when they’re transitioning out.

“We are trying to lobby the government to give veterans the best support we can when they are transitioning. Let’s give them 100 per cent of their salary.”

Ms Fimrite said armed service personnel who are not injured can normally spend up to two years retraining, and they need financial support during that period.

But for those who are injured or might suffer PTSD, a simple training programme might not be suitable.

She said: “You have to take a lot of things into consideration, not just past experiences but their aptitude and they’re interests. We find the department [of National Defence] basing a lot of decisions purely on experience and skills that [the veteran] had. You have to consider what they WANT to do. There is no point putting them in a job that’s going to trigger PTSD.

“We believe there’s a lot of opportunities like that that [the department] have to look at, and offer more money invested up front [for] care so they’re not worrying about how the kids are doing or finding a new family doctor. Give them 100 per cent of pre-release salary, then there would be less stress leaving the military and you would have more focus on getting better.

Contracts, covenants and “duty”

As Canada marks a century since the start of World War I, pomp and pageantry will play a major part. But the history of shifting attitudes and attempts to address the needs of veterans is complex.

In 1917, then prime minister, Sir Robert Borden told troops before the Battle of Vimy Ridge:

“You can go into this action feeling assured of this, and as the head of the government I give you this assurance; that you need have no fear that the government and the country will fail to show just appreciation of your service to the country in what you are about to do and what you have already done.

“The government and the country will consider it their first duty to … prove to the returned men its just and due appreciation of the inestimable value of the services rendered to the country and Empire; and that no man, whether he goes back or whether he remains in Flanders, will have just cause to reproach the government for having broken faith with the men who won and the men who died.”10

By the end of the war, there were 50 military hospitals and sanatoria with 10,754 beds.

But by 1919, Mr Borden reversed his tune, stating: “Canada has done all she could for her soldiers…this country is face to face with a serious financial situation which will call for a rigid economy and careful retrenchment.”11

In its review of a century of veteran support, Veterans Affairs Canada referred to the “implicit social covenant that must be honoured”12 that was “never an issue in party politics”.

It continued: “There have been differences of opinion about the extent of programs and their administration, but not the fundamental concept of veterans benefits or the need for Canada to have a comprehensive benefits programme.”13

Dr Allan English served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and Canadian Armed Forces and is now a history professor at Queens University and part of the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research.14 He has previously argued that rather than a “social covenant”, the relationship between Canadians and the military and veterans is more of a contract, “which can be amended”.15 There is no promise by government and Canadians, despite the perception.

Earlier this year, the government denied that there was even a “social contract”, in response to a class-action lawsuit by veterans filed at BC Supreme Court.

Lawyers stated: “At no time in Canada’s history has any alleged ‘social contract’ or ‘social covenant’ having the attributes pleaded by the plaintiffs been given effect in any statute, regulation or as a constitutional principle written or unwritten.”16

They argued that Borden’s statement was “political speeches that reflected the policy positions of the government at the time and were never intended to create a contract or covenant”.17

The ebb and flow of political tides are not new. Prior to World War II, there were changing department names and configurations, legislation, commissions of inquiry and debates about how much should or could be spent.

The attitudes – of the public and the government – also shifted when it came to veterans from indigenous communities, who initially were forced to choose between a status as indigenous, or as veteran.

Shell shock, what would now be classed as PTSD, and even the approach to suicide has changed. Mental health issues have continued to be an issue for soldiers, who the public see without outward injuries.

Dr English, in an interview with Tomorrow, points to the cost of veterans’ programmes and pensions being the second largest government expense by the 1930s 18, prompting public backlash when they could not see obvious veterans’ wounds.

By the 1990s, the image of vets at the cenotaphs was now deeply ingrained in the public mind. But at the same time, post-Cold War budgets were dwindling and there were high-profile failures in what was then perceived to be particularly Canadian spheres, United Nations peace keeping, in Somalia and Rwanda.

Since the mission in Afghanistan over the past decade, attention to and attitudes towards the military have shifted again. Though as a percentage of the population, it is not comparable to the end of the first world war, the profile is even higher.

“The idea that we’ve always treated our veterans shabbily is just not true,” says Dr English.

The original Veterans Charter, the term derived from the support programmes and benefits set in place during World War II, was updated in the New Veterans Charter (NVC) – the Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act – in 2006.19 It has not been without criticism and a formal review was set up in 2013.

The Royal Canadian Legion issued a statement in March on the NVC, arguing that the government had a “moral obligation towards our injured servicemen and women”.

They wrote: “The NVC was adopted without a clause-by-clause review in Parliamentary Committee and in the Senate because of a perceived urgent need to adopt a New Veterans Charter before troops headed for Afghanistan, to better look after modern Veterans and their families, and to facilitate their transition to civilian life. The Legion, as well as other Veterans’ organizations, supported the NVC with the understanding that it was a “living charter” which would be amended as flaws or gaps were identified.”20

The Legion did not reply to repeated requests by Tomorrow for an interview or for comment for this story.

Dr English says there are, admittedly, parts of the NVC that are problematic, such as the awarding of lump sum payments to injured service personnel. But that came about because so many of those veterans needed significant changes to their homes to accommodate their disabilities.

“Now, admittedly, the lump sum might not be big enough and I think that’s a fair argument, and there are other issues about providing long-term pension care,” he says. “But the bottom line is a lot of the changes in the NVC were, I think, positive and intended to be rehabilitating young veterans and moving the charter from just warehousing people and giving them pension into getting them back into a productive life, which has been shown to be what the young people want, and is the best for their health.

“The NVC has lots of flaws, but it was always intended to be a living document and amended, and I think that’s one of the hang-ups with it, that it really hasn’t changed as much as it should have in response to criticism.”

Mike Blais says the changes brought with the NVC provided less support to the family of a veteran than the previous Pension Act.21

“That’s when this nation lost its way,” he says. “Although the NVC was to be a living document and there were issues identified, this government is not responding. It’s not stepping up to the plate.

“It’s put this NVC on life support. And only through a great deal of pressure, a lawsuit, a protest by veterans on Parliament Hill, only have we got to the point where minister Fantino announced a comprehensive parliamentary review, with the intent of, after the committee sits, bringing forth legislation that would address some of these issues.”

Veterans Affairs Canada insists the government is committed to supporting veterans and their families.

Media relations officer Simon Forsyth said in an email statement: “The New Veterans Charter is a comprehensive approach to helping our men and women injured in the line of duty. It is about providing Veterans with the help they need for as long as they require support.

“No amount of money can compensate for a life-altering injury or illness; however, the New Veterans Charter offers real hope. It provides financial security for as long as Veterans are unable to be gainfully employed, and it offers the programs that injured and ill Veterans need to lead more healthy, rewarding, and independent lives.”22

He said the review of the NVC follows “dramatic improvements” already made by the government, and the review announced on September 26, 2013, would place “a special focus on the most seriously injured, support for families, and the delivery of programs by Veterans Affairs Canada”.

Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Ms Fimrite, with Anavets, says more changes still need to take place with the NVC. The system of managing veterans to what was meant to be more holistic. That is not working in all instances.

She says: “The government is doing a full review and they are interviewing a lot of different people. Some of the programmes could help but the eligibility requirements are so restrictive that we don’t feel they’re doing what they could be doing. There is also concern about lump sum payments – it is supposed to be strictly for pain and suffering – people don’t seem happy with that. It is hard to ignore veterans feelings on this.

“The lump sum is not working well, but it’s also not the only payment they’re supposed to be getting if injured in the line of duty. In a lot of cases, family only get support if it’s in the case plan for the veterans, but family need support in their own right.

“There are some gaping holes that we need to bridge.”

“This is the problem,” says Dr English. “Any government has to deal with the issues of their many stakeholders, all who want part of the national budget – education, healthcare, you’ve got the active military, and veterans, from their perspective, are jut another constituency. So it’s always a debate. When you see heartrending cases of people being sent home from emergency rooms because there’s not enough money for healthcare, well that’s in competition with the heartrending stories of the veterans that aren’t getting proper treatment. This is the dilemma that governments face – from their point of view, veterans are a constituency that have to be looked after, but they’re not the only one.”

Dr English says the changing tone of Borden is a typical example of government pressures.

“Governments will never … say ‘your interests will always take priority of the interests of other groups in society’,” says Dr English. “And this isn’t just governments. They do it because that’s the way the public sees it. By 1938, the effects of the Depression were still being felt and most people felt that veterans pensions were too generous because they were ok and a lot of them had shell shock, so they were apparently uninjured and they and their families were ok and other people were dependent on soup kitchens, so they turned around and said ‘no, veterans are getting too much’. Whereas in 1919, it was ‘oh no, we need to give veterans more’. The public’s perception of what veterans are due changes.”

In contrast to Dr English’s viewpoint, the Canadian government insists that support is at the top of the agenda.

Maureen Lamothe, communications advisor for the Department of National Defence said in a statement by email: “The care and support of ill and injured Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members and their families is a top priority for the CAF and the Department of National Defence.

“The CAF’s comprehensive approach to supporting our members takes into account all phases of treatment and rehabilitation – from the onset of illness or injury to the return to work or transition to civilian life.

“The goal of CAF support and care is to return personnel to duty as soon as medically possible. Following rehabilitation, and only if members cannot deploy and meet the exigencies of operations, they may eventually be released from the CAF. Upon release, care and support continue through Veterans Affairs Canada.

“CAF leadership is dedicated to ensuring each and every ill and injured member receives high quality care and support. Whether our personnel are on the road to recovery, rehabilitation, returning to work in the CAF, or transitioning to civilian life, support and guidance are available to them.”23

“Just get on with it”

The DND has used the term “universality of service” since 1985 under section 33(1) of the National Defence Act requiring that service personnel must “at all times. . . perform any lawful duty” in the military. If they cannot, they cannot remain in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Retired Lt Commander Paul Hearn, from Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Paul Hearn no longer meets that standard. He joined the Canadian navy when he was 23 and has been there for the past 25 years, rising to rank of Lt Commander, based with Maritime Command in Halifax. He originally worked as a swimming instructor and a maintenance supervisor after joining the Sea Cadets from the age of 13 until he was 17.

“I feel worn down by it,” he told Tomorrow just before he finished his time with the navy at the end of November. “It’s time to go; it’s time to move on.”

“For 25 years, there’s an inherent loyalty. You’re bred into this lifestyle.

“[But] it’s very naive to believe any organisation is looking out for you – it’s not necessarily looking after your best interest.”

LCdr Hearn was aboard HMCS Fredericton during Operation CHABANEL in April and May 200624 when he first felt the effects of rheumatoid arthritis in his hands. He was combat officer during the sting operation led by the RCMP that netted 22.5 tonnes of hashish and the arrest of three people. But the physician’s assistant on board could only prescribe Tylenol.

“I was taking Tylenol like they were candy,” says LCdr Hearn. “You just assume you’re getting older and see the medic – he is just immediate care – you just carry on and do your job. At sea, 18-20 hours [work] a day is not uncommon; things don’t stop. You’re trained to just get on with it.”

In 2007, LCdr Hearn was based in Portsmouth, England, and was referred to a specialist who diagnosed palindromic arthritis but didn’t offer treatment.

Once home in 2008, initially posted to Ottawa and then to Halifax, a “depressive element” started to set in. He spent two years on anti-depressants and only got to see a psychologist in October 2013.

LCdr Hearn says depression is looked down on, “especially in this kind of job”, and he reduced his workload in the past two years to three half days a week.

“Really they would rather I was not around,” says the father of three. “They are just getting the men out as fast as they can.

“I can see the hesitation to accept when you look at me you think there’s nothing wrong with me.”

The description LCdr Hearn says he would have applied to others in the past was “sick, lame and lazy” – and now he’s on the other side of the fence.

Dozens of former sailors from the HMCS Chicoutimi – that suffered fire damage and lost one officer while sailing from Scotland – have reported suffering from PTSD.25

LCdr Hearn says the rheumatoid arthritis is now “as good as it gets”. He owns and is landlord to 20 apartment units to keep him busy with his navy days done and will draw benefits for two years and a pension.

“We do have support,” he said. “Is it good enough? Maybe not. But if we don’t talk about it. . . It’s a cooperative issue – both sides bring something to the table and it comes down to the availability of money as well.

“We have to ensure that the Veterans Charter remains a ‘living document’ and keeps pace with changing needs and the current situation.”

“How the public feels about veterans”

With changing needs come changing governments. As well as image changes, such as the Liberal-led “Canadian Forces” terminology in 1968 and the Conservative return to “Royal Canadian” to the navy and air force in 2011, the 1959 demise of the Avro Arrow and the rise of the “Diefenbunker”, and repeated scandals – and disasters – involving military helicopters and procurement, spending varies between governments and between ministers.

And should the overhaul to the NVC not be complete before the next scheduled federal election in October 2015,26 as Mike Blais fears, they will have to start from scratch when a new government is formed, whatever the political colour.

“This is never going to see the light of day,” says Mr Blais. “There’s going to be an election. We go through these motions. I will be called to testify, so will the president of the Legion and other stakeholders who have vested interest, that need to speak to this committee to define the situation.

“But even if they come out with everything that we want, unless this government can expedite three readings and a passage within the senate within the course of a year, it’s not going to happen. It will fall the moment that the government does and that will be the end of it.

“We have to start at square one again. I find it frustrating. Here we fought so hard to get this, and yet the reality is they waited so long that chances of us actually affecting the changes needed through this process will be negated when the government falls. Who knows what will happen next time Without passage of legislation, nothing’s done.”

Dr English says the media will emphasise the story of the day, and veterans only get attention when something bad happens.

“It’s not a story, ‘system works well; people being looked after’,” he says. “I think as we’ve seen in Canada with a lot of mental health issues, there’s still a lot of stigma attached. The problem is in Canada there are a lot of people who deep down inside believe that shell shock, PTSD, are caused by weakness in the person. ‘So, why are we dealing with this?’

“And that’s exactly what happened in the 1930s. People were saying, ‘Look at all these people with shell shock, they look perfectly healthy to me and they’re getting this huge generous pension and I’m unemployed’. I think you see a bit of the same thing today. I think people are more aware now, but it’s still a huge problem even outside of the veteran and military community, the stigma around mental illness. ‘They couldn’t handle it.’ That’s a huge challenge in dealing with the issue.”

Mike Blais says attitudes need to change both within the military, and in the wider public. And the public must improve its actions towards armed service personnel, just as must the government.

“I think some people need a reality check,” says Mike Blais. “We’re a brotherhood and a sisterhood. These are wounds – this is what we have to instil in the minds and in the hearts of the brother and sisterhood. We are the first line of defence.

“We need a change of mindset and it has to start now. We have the obligation to our wives, to the children, to the serving member who’s wounded, and we have the obligation to treat them with the same damn level of respect as we would to anybody who has been wounded.

“Where’s the community spirit for those that are suffering from mental wounds? It’s not the same. And that’s symptomatic of the problem. Because these families need the same level of support. If you would reach out to a wife who has a husband who has lost a leg or may need some demonstrable injury that you can see visibly, well why can’t you reach out for those that you can’t see, who are suffering from mental wounds, who are confronting very serious medical issues and need our help?

“I think the civilian community must be prepared and understand that there are thousands of Canada’s sons and daughters that will soon be returning to our community. And that they will need our help. Not every wound is visible.

“DND can’t do this alone. Veterans Affairs can’t do this alone. They’re not in control anymore once these men and women come back to our communities.”

He adds: “If we don’t recognise their sacrifice, if we don’t step forward and make sure that the psychological, the medical and the social resources that they need to assimilate into our communities and thrive and be a part and live good quality of life, we’re failing them. We cannot afford to do that. There have been 40,000 men and women who have deployed to Afghanistan and we can’t afford to fail these people now in their time of need.”

LCdr Hearn says there was a “coming of age” in the military where personnel were being looked at as individuals, finally, after considerable time.

“There is still a reluctance to acknowledge that. I think we have to be more accepting,” he says. “They are coming around, slowly.

“The expression is, ‘if you’re not deployable, you’re not employable’. But if we keep showing these people the door, we’re not solving any of these problems. We have to be more focused on admitting that they’re people who need help.

“We are not going to undo it overnight. Look at World War I where we called them ‘yellow cowards’ and it took 80 years to get to accepting PTSD. There’s a lot of well-intentioned actions.”

Dr English says this is a constantly changing story, pegged to perceptions of the military and the roles they have carried out in different corners of the globe.

“In the 1990s, people held the military in very low esteem and weren’t prepared to do anything for veterans, except for second world war veterans,” he says. “It was a terrible attitude, but that’s how people felt.

“It’s not so much the government or ‘them’ as people say, but the general public. You can have a heart rending story about a veteran one day, and then you can have a heart rending story about the lack of medical care in the community and then these same people you turn around to them and say, ‘well of course we can address all these issues but we’re going to raise your taxes’. And they say, ‘No thanks’.”

What image do Canadians have of their military and veterans? With the end of the Afghanistan mission, what image will dominate the coming decades?

“I guess there’s a certain cynicism that I have as a historian, that the public on one hand is quick to show sympathy to the plight of anyone, and on the other hand when you ask them to raise taxes, ‘well no, we don’t do that’. It comes back to the fact that governments have to make choices amongst constituencies and sometimes the veterans are on the winning side and sometimes they’re on the losing side.

“We have to realise this: it’s not going to be all bad or all good, it’s going to be a continuously changing scenario depending on how the public feels about veterans.”

CORE PRINCIPLES APPLIED

No issues for principles 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10 or 11.

5. Comfort the afflicted and afflict the complacent and 8. Be a safe harbour for the public and staff: This is a joint issue. Under both these principles, it is Tomorrow’s style not to use the term “commit(ted) suicide”, and to encourage readers to seek help when reporting on the issue of suicide.

- Prime Minister Stephen Harper statement. ↩

- Coverage of the dispute over which suicides are “counted”, here and here ↩

- http://www.canadianveteransadvocacy.com/ ↩

- A list is available here and there are also reports from here and here. In a report by the Canadian Armed Forces on suicide between 1995 and 2012, they argued there was “no statistically significant change in male CF suicide rates” and was “lower than that of the general Canadian population”. It also stated: “History of deployment is not a risk factor for suicide in the Canadian Forces”. Read the report here. ↩

- Read the full VAC statement here. ↩

- Further details on the closure and reaction can be found here. ↩

- http://julianfantino.ca/ ↩

- http://anavets.ca/ ↩

- Details of the 75 per cent pre-release salary, and recommendations to raise it, are contained in the Veterans Ombudsman report from April 2013. ↩

- Quoted by Robert Fair, MP, House of Commons, Debates, June 14, 1944, 3816. See page 3 of “The Origins and Evolution of Veterans Benefits in Canada 1914-2004”. ↩

- Quoted from page 231 of “Shaping the Future”, referencing Desmond Morton and Glenn Wright, “Winning the Second Battle: Canadian Veterans and the Return to Civilian Life” (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 124. ↩

- See page 1 of “The Origins and Evolution of Veterans Benefits in Canada 1914-2004”. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Dr Allan English, Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research. ↩

- See page 231 of “Shaping the Future”. ↩

- Attorney General of Canada response to Amended Notice of Civil Claim, No S-127611, paragraph 100. Read the full response here. ↩

- Attorney General of Canada response to Amended Notice of Civil Claim, No S-127611, paragraph 103. ↩

- Page 233 of “Shaping the Future”. ↩

- Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act. ↩

- Royal Canadian Legion statement. ↩

- 1985 Pension Act. ↩

- Read the full VAC response here. ↩

- Read the full DND response here and further info here. ↩

- Operation Chabanel. ↩

- HMCS Chicoutimi town hall meeting. ↩

- 2015 election fixed date. ↩