This investigation contains words, images and videos which may be offensive to some readers

Screen grab of RBS/NatWest ad “The House that Jack Built”. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Feathers on TV

THE TV advertisement for the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and NatWest banks shows a child running around in his feathered headdress, a tipi standing next to patio doors as he recounts how his parents got a mortgage so “they could have me”.1

An Enterprise car hire commercial also shows a child running around in a headdress, this time screaming and terrorising the staff as they talk about their great “US customer service” for UK rentals.2

New banking app B, from the Clydesdale Bank and Yorkshire Bank, sells itself on the premise that, “We aren’t born worrying about money”, showing children playing multiple fantasy roles from astronaut to criminals to knights, all crossing over each other. It includes youths with feathers in their hair and face paint running in a circle making “waw-waw” gestures with their hands to their mouths.3

Enterprise did not reply to repeated requests for comment. Ben Jun-tai, a spokesman for RBS/NatWest, said: “The outfit and props were simply to show a child having fun. As such I’m afraid we won’t be making any comment.”

In a response to questions, Carol Young, a spokeswoman for CYBG plc, the holding company that owns Clydesdale and Yorkshire banks, said: “The aim of the ad was to recreate the child-like world of play and, as you say, it depicts a range of scenarios involving some of the many games played by children. We would not able to disclose either costs or revenue.”

Is it harmless fun or using children to make money out of another culture? What is the definition of cultural appropriation? Why is wearing headdresses such a frequent target for campaigners and such an offence – both moral as well as cultural – to Indigenous communities? And could their use in the UK even be breaking laws?

Playing dress up

Chelsea Vowel is so used to explaining cultural appropriation to white people she’s a bit fed up with it. It’s usually the only interaction the majority population ever has with a minority – when the majority does something wrong and gets criticised for it.

Beneath the issue of headdresses, the most common point of contention, there are other objects and images taken from Indigenous peoples and used by others.

Ms Vowel said a key difference is between representation and appropriation, concepts that often get confused in the controversy over objects or imagery.

Representation might not use restricted symbols, such as headdresses, but it can be just as harmful by homogenising hundreds of different and distinct nations into one group, to be potentially ignored, marginalised, oppressed or killed.

Moccasins, feather earrings, the tipi – those would generally not be restricted as images, though aspects of tipis can also be sacred.

She explained: “Representation is dealing with things like unrestricted symbols, things that are not particularly sacred within the cultures.

“You have people who will dress up like that or use those symbols and what they’re doing is harking back to that homogenised Plains Indian sort of image that has been created by Hollywood. You’re not taking sacred symbols and mocking them, you’re perpetuating a stereotype that homogenises 600-plus different nations – very, very diverse nations.

“There are only a handful of Plains nations and somehow our symbols get used to represent all Native Americans or all Indigenous peoples in North America. And in doing that, in accepting those sorts of portrayals, people lose out on understanding our diversity, both in symbols and culture.

“So they won’t learn anything about the Inuit, they won’t learn anything about the Mohawk, they won’t learn anything about the west coast cultures – it’s just Plains Indians all the time. And that becomes an issue because we’re really invisibilised.

“We’re four per cent of the population in Canada, two per cent of the population in the United States. We’re a super minority. And yet we are the original peoples on those lands and nobody really knows anything about us, other than these representations.

“And we’re fighting back against that so intensely because we need people to see us. And they don’t see us.

“If we don’t present in that stereotypical form that even people in the UK are used to seeing, then they don’t see us, they don’t take us as authentic, they don’t understand that we’re actually present in the 21st century, dealing with very, very serious issues.

“Representation for us is such a problem because it hides us. And so that’s one issue. And it’s a serious one.”

Prof Daniel Garneau said cultural objects might be made by Indigenous peoples but the versions for public consumption would lack sacred elements and would be “policed” by members of the community.

“And then within those communities or outside those communities but membership with those communities, there are artists who are working not as cultural producers but may use their culture’s material in avant garde way and that might upset some elders and traditional people but usually they permit it,” he said.

“There are certain – at least where I’m from around here – protocols that permit artists from a community to do things like that, but if it went too far, you’d be corrected, [though] not in any kind of legal way.

“Then are prohibitions against Indigenous people from one community using the representations of another, so sometimes those are clan affiliations and sometimes they’re just any kind of representation. These are looser and more about being admonished or something.”

He said there was general agreement non-Indigenous peoples should not use representation from any Indigenous peoples.

But, he continued: “If, for instance, a white guy does a painting of a bear, bears aren’t Indigenous or wolves or eagles or anything like that – it’s the style that might have some pretty obvious lineage.

“There are all sorts of Indigenous crafters who are making Indigenous clothing and jewellery and they want non-Indigenous people to wear them and that can be cited as respectful. But clearly anything spiritual or sacred – which don’t include tipis – but pipes, anything to do with ceremony or regalia like headdresses, yeah, that’s probably going over the line.

“There are some things that are clearly offensive and they were intended to offend. There are other things that are clearly offensive and the person was clueless and usually they’re contrite when they understand that.”

Much like the “tipi folk” living in UK structures for decades as mentioned in Part 1, there are others in continental Europe “truly fascinated”, said Prof Garneau. But is that fascination a launch pad to learning more about Indigenous peoples?

“It’s probably unlikely to happen in those particular cases,” he said. “If you were serious about that and included contemporary Indigenous peoples or even people at a powwow or however they’re performing their culture, that would be interesting, but that aspect would be irrelevant in a setting like Britain I would think.

“The only reason why those things exist, would seem to me, is at a very low level as simply a rough signifier of indigeneity and not intended as an entry point to anything wider. And that’s why I would class it as a form of nostalgia for a white imaginary, rather than as something meant to be offensive or meant to be a gateway into contemporary indigeneity.”

Earning it

Unlike representation, appropriation relies on individuals – almost always claiming “freedom of expression” – to dismiss the original culture and use restricted symbols. And the example Ms Vowel consistently uses to teach this point is both military medals and university degrees: they have to be earned.

“You go to university, you get your parchment, that parchment is a symbol of what you’ve achieved,” she said. “And people will and can go out and replicate them, but at that point, when you start doing that, when you start faking parchments and you start faking military medals, you start running into criminal sanctions.

“It’s not just in poor taste at that point. You’re actually doing something actively wrong, you’re misrepresenting yourself in some way. And sure, people can get away with it, but that’s not the point. You’ve crossed a line there because you’ve taken a symbol that is only supposed to be applied to certain people and you’re faking it.

“And I think a lot of people, especially with military medals, they can understand right away why that’s offensive. They’re like, ‘No, that’s just wrong’ because it represents something really important.

“And go ahead and mock it if you want but don’t pretend that you’ve earned one.”

[Tweet ““And go ahead and mock it if you want but don’t pretend that you’ve earned one.””]

Ms Vowel readily admitted she would love to wear a Plains headdress, a beautiful item and important to her culture. But it’s restricted to certain individuals and she can’t.

“So it’s really, really galling to have someone from outside the culture who thinks that they can just do that, they can just put it on and it’s no big deal because they don’t have to follow our cultural restrictions,” she added.

“Well no, they don’t have to – we have no way to coerce people – we have to convince them that it’s not okay.”

False representation as different roles or statuses in the UK, rather than races, has been subject to court cases and public backlash.

A 26-year-old man was found guilty of impersonating a police officer in Scotland and pulling over drivers with flashing lights, when in fact, he was a stripper.4

In 2010, a man attended a Remembrance Day parade wearing medals he was never awarded. He was arrested and later pleaded guilty to “unlawfully using military decoration”. The 1955 Army Act stated it was an offence to “falsely represents himself to be a person who is or has been entitled to use or wear any such decoration, badge, stripe or emblem”.5 The US has a similar act, the Stolen Valor Act against those trying to “gain recognition or prestige” by wearing awards they weren’t given.6

Fake university degrees have been a frequent target of immigration officials and right-wing media outlets, but fake qualifications also come up in court cases.7

But both impersonating someone of a particular role or status, or claiming fake qualifications, are offences in the UK only for those recognised roles. Because Indigenous peoples are not recognised, their military statuses or qualifications can’t be impersonated.

The UK signed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007.8.

Article 11 states: “States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution, developed in conjunction with Indigenous peoples, with respect to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions and customs.”

And Article 31 states: “Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.”9

Cultural objects have been part of Indigenous life since the beginning, but also became part of their economies, even more so when colonialism began and there was a tourist desire for what outsiders decided was stereotypical.

But the need to feed foreign lust for “other” was the fault of the colonialism too, which destroyed the original North American economies, explained Ms Vowel.

“In some cases you have whole areas where the majority of people who are self-sufficient are artists,” she said. “So yes, of course, we’re producing and have been for a long time, for the western gaze, but trying to also integrate our own culture into these art forms.

“Those things are for sale, but I think they’re also attempting dialogue. When you’re looking at things that we’ve created, there’s a lot of culture embedded in those objects and we’re trying to share a world view, and I think that gets missed because it’s just looked at as ‘cute’ and ‘primitive’ and all of these other disparaging words that are used to downplay our artistry.

“The fact that sometimes some of those things are commercialised, people get the sense that, well, everything is commercialised. But that’s not true at all.”

Ms Vowel said the imagery used in Indigenous commercialised products is very deliberate and careful. While it would be possible to find Indigenous peoples selling headdresses, that doesn’t mean it’s okay to buy them. Often masks or totem poles, for example, are made without sacred images, she said, but the general public would not tell the difference.

“It’s part of a collective culture, it’s not an individual culture – an individual person cannot give you permission to access restricted symbols,” she asserted. “Restricted symbols – symbols that are only available to certain people within our culture – those things don’t tend to become commodified.

“You have people who are taking our symbols or taking the symbols that they think we have – because it’s not always accurate representation – and commodifying it and making money off it and we don’t benefit in any way and it doesn’t increase understanding about our issues, it doesn’t increase understanding that we actually exist as people in the 21st century. It doesn’t do anything for us.

“And then you have people who are actually ripping off our sacred symbols and that’s actively damaging us in an even worse way. Because it’s taking things from us, the items, the symbols, the ideas that we have restricted and it’s just giving everybody free reign to access things, which is something we certainly don’t consent to.”

There is no outward signal to Indigenous peoples that majority cultures want to learn about the minority cultures they are picking and choosing from. The message received, said interviewees, is: “They don’t care about us.”

Activists and artist RJ Jones said: “Because if they did care then they wouldn’t have used the design in the first place because they would have done the research.

“It’s like the headdress – people are using it for fashion but it’s not at all fashion. Headdress is Plains culture and people using that excuse, ‘Oh I’m part-Native too’, the nation you are ‘part of’ probably didn’t even use headdress, so again, there’s that discrepancy inside of culture itself.

“People are wilfully ignorant because they don’t want to have, I guess, the consequences of knowing that they screwed up.”

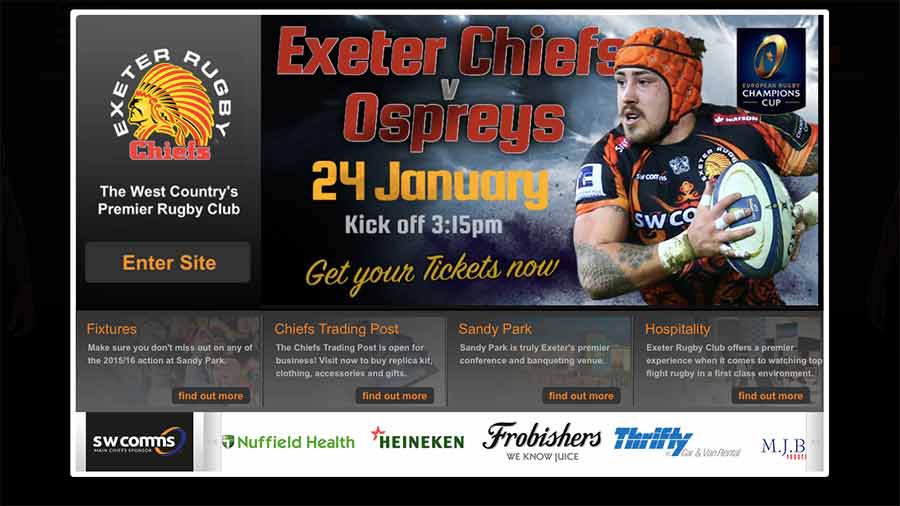

Screen grab of Exeter Chiefs website. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

The Spread of ‘Chief’ and ‘Red’

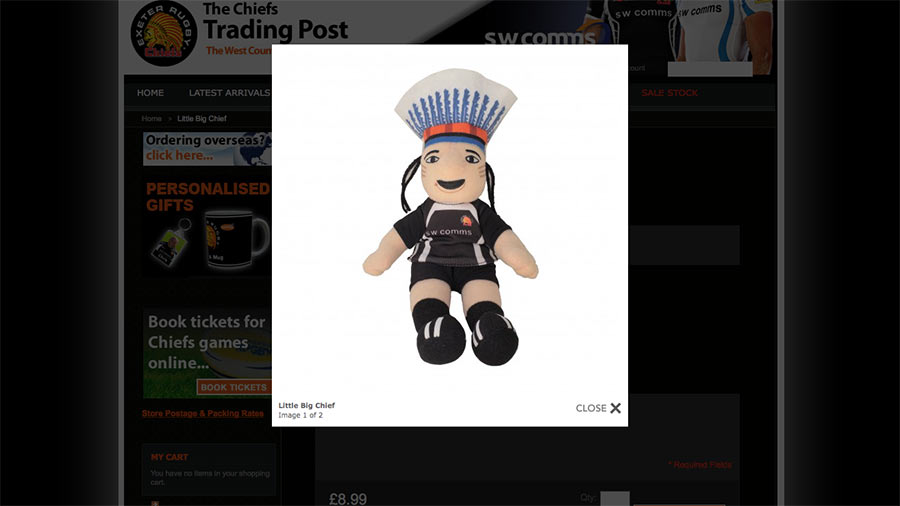

The Exeter Chiefs rugby team have used the logo of a headdress-adorned chief to propel their marketing and turnover from £19,200 the year before the name change from Exeter Rugby Club in 1999, to £13.2 million last year.10

When asked about by Tomorrow about their name, logo, merchandising and how much of their growth could be traced to the use of “Chiefs”, the club declined to make any comment.

Though the uses of Indigenous identity for sports team names and logos are considerably more rare than in the United States, the most prominent dispute over the issue is not unknown: Washington DC’s football team.

On June 18, 2014, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) of the US Patent and Trademark Office cancelled the Washington football team name “Redskins” and logo as a registered trademark because it was “disparaging”.11 It was the second time they had done so, having a previous ruling overturned. Past imagery used by the team included a tipi on the team’s programmes, headdresses as part of the marching band uniforms, and the “Dancing Indians” or Redskinettes.

In its 2014 decision, the TTAB stated the term “is and always has been a racial designation” and “refers to the real or imagined skin color of Native Americans”. It was not in a dictionary prior to 1966 and thereafter only as an offensive term, and it has been subject to opposition campaigns since at least the 1960s.12

The TTAB found that through national organisations, at least 30 per cent of Indigenous people in the US found the term disparaging.

It went on: “Thirty percent is without doubt a substantial composite. To determine otherwise means it is acceptable to subject to disparagement 1 out of every 3 individuals, or as in this case approximately 626,095 out of 1,978,285 in 1990. There is nothing in the Trademark Act, which expressly prohibits registration of disparaging terms, or in its legislative history, to permit that level of disparagement of a group and, therefore, we find this showing of thirty percent to be more than substantial.”13

“There is an overriding public interest in removing from the register marks that are disparaging to a segment of the population beyond the individual petitions.”14

The ruling was upheld by a district judge in July 2015, then struck down by the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals in December 2015. The US Supreme Court declined to hear the case but will instead rule on a similar one, which could affect the Washington team.15

The shop for the Exeter Chiefs, the “trading post”, sells items such as this white figure in a headdress. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

In the UK, a trade mark similarly can’t be “offensive”16 but the “Washington Redskins” remains a registered trade mark in the UK and across Europe through a German firm.17

And in August 2016, an application was added to the register from the NFL trade marking “Hail to the Redskins” on clothing and “education and entertainment services”.18

In contrast, the US state of California has banned the word and any teams will be unable to use it from January 1, 2017.19

Prof Garneau said there were mixed opinions on some logos and team names contrasting ones such as the Cleveland Indians and Washington Redskins, both “clearly offensive – they’re meant to caricature, not to respect”.

But he said some voices fewer representations of Indigenous peoples could also be problematic.

“I don’t think representations of Indigenous people are always and only racist. They’re usually problematic and can be in poor taste,” he added.

The Exeter Chiefs chose their name in 1999 with fans then adding the “tomahawk chop” chant and Devon Teachers Rock Choir even perform a mock, Indigenous-style backing for the team. The video has since been removed from YouTube following a press query by Tomorrow. A copy was made before it was taken down and a short clip made for evidence.20 Both the chant and “chop” appear ripped from the Atlanta Braves baseball team, both widely condemned in the US for being offensive.

Were the chant in Scotland and at a football match, it might fall foul of the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act, based on it being “behaviour that a reasonable person would be likely to consider offensive” on the grounds of race.21

Debbie Kent, for the choir, told Tomorrow by email: “The Devon Teachers Rock Choir prepared the Tomahawk Chop specifically for a pre match pitch performance for the Exeter Chiefs Premiership Rugby Club on Sunday 20th March, 2016. This is the only time the chant has been performed by the choir.”

The Exeter Chiefs, said Dr Pratt, might argue they are “honourable”, as the Washington team claim, using the “power of the chief and his presence giving people strength as a community”.

But she has attended games where fans do the “chop”.

“I’ve been to a couple games and they start in the stalls going ‘woo woo woo’ doing a chop on their arm, like a scalping chop or something, and it’s really rude and I think that people just don’t see it,” she said. “They’re not aware that there are people in that audience who are finding that offensive. They just don’t know.”

But she admitted she did not take advantage of the British Museum visiting Exeter Museum with their “Warriors of the Plains” exhibition, to begin some education and at least stop the “chop”. “That would be a start,” she added.22

“I’m truly on the side that we can mediate, that we can find a solution, something that’s acceptable to everybody.”

While the Washington football team is still promoting its trade mark, the Streatham “Redskins” ice hockey team announced in 2015 they were dropping their own name. The team did not reply to press queries but in their original press release, they stated:

“A lot has changed since those days in the 1970’s where a set of replica Chicago Blackhawks jerseys influenced us to call ourselves the Redskins. This was done at the time with the best of intentions as it invoked a sense of fierce warriors and was way before any negative or divisive connotations were associated with the name.

“As a progressive and forward looking team who want to attract new supporters, encourage more local kids to join our junior club and create a positive image for ice hockey within our great city we have decided to drop the Redskins name from our team at the end of this season. We have not taken this decision lightly and realise that many of our long time supporters may not agree with the change, but we hope they will understand.

“We must point out that it is not our intention to take sides in the Washington Redskins NFL debate. America is not England and Washington is not Streatham. It is about making the correct decision for us and not to dictate policy for anyone else.

“We have had no pressure to change the name from any politicians, councillors, sponsors or press here in the UK so the decision is ours alone and we wish to make that clear.”23

Figurines on sale at the German Christmas Market in 2015 in Glasgow, UK. Similar figures are on sale in 2015. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Advertising as racism

At the 2015 Christmas German Market in Glasgow, Scotland, figurines were on sale of “Red Indians, £22 each”, bulging, cartoon-like eyes, sitting cross-legged with a pipe on their lap. The woman behind the counter could not explain their origin, merely that they came via her boss in Germany.24

Nearby headdresses, often in bright rainbows of colours, hanging on walls like scalps, are easily available in the Eurasia Crafts shop25 in the centre of Glasgow amidst dreamcatchers, T-shirts with Indigenous figures staring off into the distance, and objects from multiple other religions and mythical creatures such as dragons.

Nearby headdresses, often in bright rainbows of colours, hanging on walls like scalps, are easily available in the Eurasia Crafts shop25 in the centre of Glasgow amidst dreamcatchers, T-shirts with Indigenous figures staring off into the distance, and objects from multiple other religions and mythical creatures such as dragons.

Less than 10 minutes walk from the shop first opened in 1971 is the birthplace of Canada’s first prime minister, John A Macdonald. He was committed to the assimilation of Indigenous peoples and was superintendent general of Indian affairs during the push to ban their culture, such as traditional ceremonies and more. It is increasingly argued he is guilty of “cultural genocide” if not genocide more widely.26

Eurasia Crafts did not reply to requests for comment. Glasgow City Council confirmed they had received no complaints about the store, nor about the Christmas German Market items through their trading standards department.

Headdresses and other items from Indigenous cultures or depicting Indigenous peoples for sale at Eurasia Crafts in Glasgow, UK. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Why are headdresses and the debate about appropriation something that continue to be the subject of debate, beyond, for example, a lack of clean drinking water in Indigenous communities or murdered and missing Indigenous women? Ms Vowel had a theory.

“It’s one issue that actually impacts non-Native people,” she said. “Drinking water on reserves doesn’t affect non-Native people – you’re not on reserves, you have fine drinking water.

“All these other issues, they’re horrible and you could look at them and be like, ‘Oh that’s terrible’ but it doesn’t actually impact non-Native life.

“But the issue of can you access these symbols? Can I wear this? Can I do that? That impacts on people’s lives; that touches them personally.

“Because it’s closer to them, that’s what they talk about and that’s what they feel strongly about because all of a sudden it’s about them.”

She continued: “It’s interesting that this issue is sort of the wedge into the feelings of non-Natives. Because it seems like a sort of a pointless issue. Like we keep going around it and it’s like why is this even important? But it’s the one intersection between our culture and how non-Native people feel about themselves.

“It’s a weird wedge. But I feel if we can get people to start thinking about it in more nuanced ways, then they will start to see the range of other more important issues out there, and then start to make the linkages about how those things actually do affect them, just not as directly, personally.”

[Tweet “”It’s the one intersection between our culture and how non-Native people feel about themselves””]

The examples of the RBS/NatWest, B app and Enterprise ads with a child in a headdress made Dr Pratt uncomfortable.

“The words ‘Native American’ or ‘Indian’ are never mentioned, so in a way that’s even more ignorant, because it’s not even acknowledging that this is a real culture,” she asserted. “It’s just this is what kids do and they can goof around and do whatever they want and that’s really freedom.

“An ad like that, I don’t think people understand how insidious media is in their lives, how it’s a drip, drip, drip of this is the right way to do things, the nice mother stays at home and looks after the kids, the father that goes out to work, the nice little kids who do what they’re told – it’s so invasive into our lives and to have something like a culture stereotype inside it, what would just be a pretty banal ad, is really potent.

“There’s a lot of Native American people [in the UK] and they see that, but they’re such a small community that they just think one voice in the middle of the field isn’t going to make any difference. And so I think yeah someone needs to stand up and say something, otherwise it will just carry on.”

She added: “I think there is this view that the Native American has gone. They are not part of our society anymore, they are some past culture that’s gone into the setting sun or whatever cliché. I really think people think that, and that’s really sad.”

Shelley Niro was even more blunt: the advertising is colonialism and racism.

“When I see something like [the ads], especially from a Native point of view looking at non-Native imagery, it is colonialism,” she said. “It’s a construct of that whole idea of, ‘Let’s go conquer some land and we’ll bring back the goods’.

“There’s a certain feeling of possessiveness and ownership and those symbols that are shown like that, it’s like, ‘These are ours now so we can do what we want’. And I don’t think Britain would really look at that and have a discourse around the whole imagery.

“It is about ownership and possessiveness and making it okay to play with kind of imagery. In the end, it’s really racism.”

If the conquerer – and their descendants in the British advertising world – get to decide who is Indigenous, their looks and their culture, how do Indigenous peoples define themselves against that onslaught?

PART 3 – Dress for the part

- The banks made parallel and virtually identical ads, but with a different child actor in each, one with a Scottish accent, one English, to cater to RBS and NatWest national markets respectively. Ads accessed most recently on December 4, 2016. The RBS ad is no longer visible on Youtube, but Tomorrow has made a copy. ↩

- Enterprise ad is no longer public on Youtube but a copy exists at campaignlive.co.uk, accessed most recently on December 4, 2016 ↩

- The ad can be viewed on Youtube, accessed most recently on October 19, 2016 ↩

- “Officer stripogram found guilty”, BBC news, accessed most recently on October 30, 2016. Legislation on the subject is quite broad, stating it is an offence if someone “(b) wears any article of police uniform without the permission of the police authority for the police area in which he is, or (c) has in his possession any article of police uniform without being able to account satisfactorily for his possession thereof”. However, it is is not an offence if part of a performance – “Nothing in subsection (1) of this section shall make it an offence to wear any article of police uniform in the course of taking part in a stage play, or music hall or circus performance, or of performing in or producing a cinematograph film or television broadcast.” ↩

- “Is it illegal to wear medals you weren’t awarded?” BBC News, January 10, 2010. The Army Act 1955 legislation was superseded by the Armed Forces Act 2006, and it is unclear if the provision still stands. Sites accessed most recently on December 4, 2016 ↩

- The 2006 act was later struck down by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional against freedom of speech and replaced by a similar act in 2013. Both accessed most recently on October 30, 2016 ↩

- “Bogus forensic expert faces jail”, BBC News, February 21, 2007. UK Naric, the national agency for recognising international qualifications, ran a 2015 blog post about “Fraud: a growing problem in education, and how to guard against it” but it is unclear under which legislation this issue is covered. Both websites accessed most recently on October 30, 2016 ↩

- Background on the process and declaration, accessed most recently on October 30, 2016 and UN general assembly debate points on the declaration. Canada and the US were two of four countries who voted against UNDRIP, though Canada removed its objection in May 2016 and the US has signalled some retreat. ↩

- Pdf copy of the full declaration. ↩

- Companies House, which incorporates and dissolves limited companies, holds the filings for firms including Exeter Rugby Club Limited, company number 03320422. Full accounts for the year ending June 30, 2015 showed a turnover of £13,222,843. Full accounts for the year ending May 31, 1998 under the name County Ground Promotions Limited showed a turnover of £19,200. Website and accounts accessed most recently on October 30, 2016 ↩

- TTAB cancellation no. 92046185, “Amanda Blackhorse, Marcus Briggs-Cloud, Philip Gover, Jillian Pappan, and Courtney Tsotigh v. Pro-Football, Inc.” Indigenous mascots were also condemned by the American Psychological Association in 2005 because “they remind American Indians of the limited ways in which others see them. This in turn restricts the number of ways American Indians can see themselves” – Dr Stephanie Fryberg, University of Arizona, accessed most recently on November 13, 2016. ↩

- TTAB cancellation no. 92046185, pages 59-61. ↩

- TTAB cancellation no. 92046185, pages 71-72. ↩

- TTAB cancellation no. 92046185, page 77. ↩

- “US top court refuses to hear Redskins trademark appeal”, Reuters, October 3, 2016, accessed October 30, 2016. ↩

- “What you can and can’t register”, UK government. The Trade Marks Act 1994 refers to “accepted principles of morality”. Both websites accessed most recently on October 30, 2016 ↩

- UK case details for trade mark EU003166774, accessed most recently on October 30, 2016. ↩

- UK case details for trade mark UK00003166324, accessed most recently on October 30, 2016. ↩

- California Racist Mascots Act, signed into law October 11, 2015, accessed October 30, 2016 ↩

- Rugby message board about the “chop”. The choir video is now offline. Facebook page for the choir, accessed most recently on October 30, 2016. ↩

- Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Bill, accessed most recently on October 30, 2016. ↩

- Blog on “Warriors of the Plains” exhibit, accessed on December 4, 2016. ↩

- “Club announcement for 2016/2017 and statement on “the future …” of the club name. Both pages accessed most recently on October 30, 2016. ↩

- The market in 2016 again has the items, though without labels. The set up is run by Market Place Europe Ltd, website accessed on December 4, 2016. ↩

- Website for Eurasia Crafts, accessed on October 30, 2016. ↩

- Macdonald was superintendent general of Indian affairs (1878–87) and An Act Further to Amend The Indian Act, 1880 making it a criminal offence to carry out various cultural practices. More information can also be found in the full text of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996, accessed on December 4, 2016. ↩