This investigation contains words, images and videos which may be offensive to some readers

A tipi for the nursery of Chatelherault Primary School in Hamilton, UK. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Teaching how to name – and claim – land

In quiet suburban Silvertonhill Avenue in the town of Hamilton, Scotland, there lies Chatelherault Primary School and its nursery.1 And in front of that, a wooden tipi with holes cut to allow young explorers to weave in and out.

A costume on sale at Dazzle Fancy Dress in Hamilton, UK. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Children in the town can also buy an “American Indian Squaw” costume, sold year-round at Dazzle Fancy Dress – “includes dress and headpiece” with bow and arrow to “complete the look”. The outfit with a highly offensive term is made by Rubie’s in the US, a firm having exclusive rights to all Marvel and Disney characters as well as different race categories.2

For the adults looking to buy a tipi for their youngsters instead of a costume, an easy way is through a firm such as catalogue giant Argos, recently bought by supermarket Sainsbury’s. Within their training for staff is a cartoon figure, feather in his hair, one hand raised, saying “Woah there cowboy”.3

Screen grab of training program used for staff at catelogue retailer Argos in the UK, submitted by a member of staff. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

From young to old, Indigenous images and colonialism are engrained more deeply in education in the UK than just school yard equipment or corporate training.

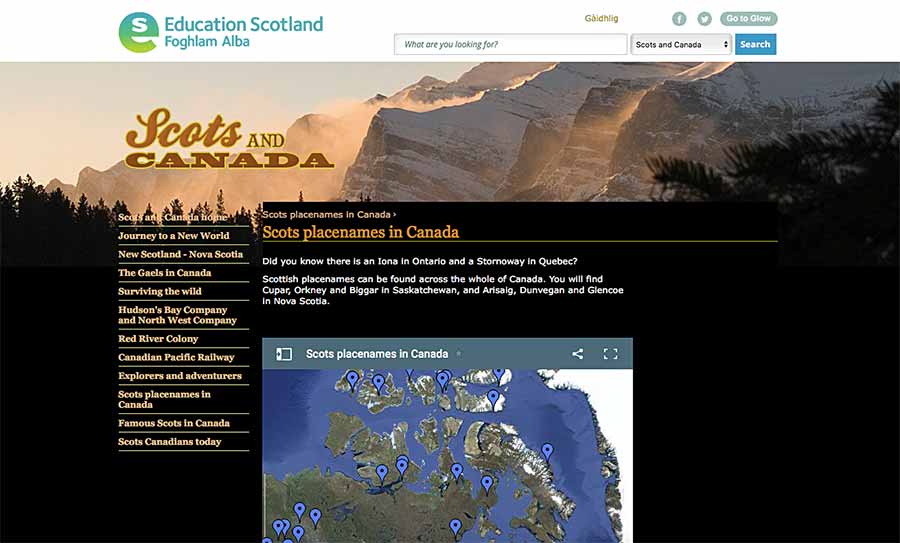

Scotland’s government education agency has a dedicated website on the historic links between the nation and Canada, focusing particularly on the exploring and adventurous Scots and their successes in the “New World” in the face of adversary.

It also promotes Canada’s first two prime ministers, John A Macdonald and Alexander Mackenzie, but without mention of their impact on Indigenous peoples.

It boasts: “The Scots in Canada became fur traders and settlers, explorers and adventurers. They became successful politicians, led rebellions and incited uprisings. Scots built businesses, communities and were instrumental in the founding of the Canadian Confederation.

“Scotland was just one of the countries that contributed to Canada’s history, but for such a small nation it had a large impact.”4

And the limited lore of settling is set out as: “Many Scots, lured across the ocean by the promise of free land grants, discovered that the new settlements were still more than a thousand miles away.

“New Scots settlers were often afraid of the people of the First Nations. In Europe, the Indigenous People of North America were described as ‘Red Indians’, as savages, and tales of scalping and Wild West massacres were well known.

“In reality, many Native tribes had become accustomed to trading with Europeans. Although some groups were hostile to white encroachment on their traditional hunting territories, relations between immigrants and First Nation peoples were generally peaceful.”5

And Hamilton is one of hundreds of Scottish place names laid out in a map of all those across Canada bearing Scots identities, a city near to Six Nations of the Grand River.

The “free land” given to Scots and others was taken. And that legacy was firmly linked to those first claims of explorers centuries ago, usually cemented with new names to replace ignored Indigenous ones. The heritage of appropriated Indigenous place names, such as Oklahoma, Manitoba or Dakota, is usually overlooked.

Asking if nursery children were given an education about Indigenous peoples, South Lanarkshire Council’s head of education Tony McDaid told Tomorrow by email: “We have a wide range of outdoor play equipment at our nurseries across South Lanarkshire which is designed to encourage active and creative play, the wooden den at Chatelherault Primary is one such example of this and was put in place after the new school opened some 10 years ago it is very popular with the children in the nursery class.”

Argos did not reply to requests for comment and neither did Dazzle Fancy Dress.

Education Scotland, though their website states is is copyright of the Crown, said they could not speak for the Scottish Government on whether it recognised Scotland’s colonising past.

Screen grab of “Scots in Canada” website from government agency Education Scotland, showing all places in Canada with Scottish names. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Tracy Reilly, communications manager with Eduction Scotland, told Tomorrow by email: “This website is in the process of transferring over to the Scottish Association of Teachers of History and they will make all future decisions on further development of the site.

“There are a number of resources on the Education Scotland website which explore Scotland’s attempts to set up trading colonies, and to settle new lands, for example in South America in the 1700s.”

Tomorrow also asked if any there had been any communication with Indigenous peoples about Scotland’s colonial education programme. Ms Reilly replied: “To our knowledge there have been no discussions of this sort.”

Why should UK education matter to Indigenous peoples in North America, or vice versa? And is history just history, or is it still dominating both economies today?

Doctrines of ownership

For many, colonialism is not some past event easily dismissed to history books and lecture theatres, particularly when Indigenous imagery is thrown back at those people most harmed by it.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Canada (TRC), which reported in 2015, called for an end to the concept of the Doctrine of Discovery, the historic basis for claiming North America and elsewhere, but linked directly by the commission to the deadly and destructive residential school system.

Its final report introduction bluntly states: “For over a century, the central goals of Canada’s Aboriginal policy were to eliminate Aboriginal governments; ignore Aboriginal rights; terminate the Treaties; and, through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada. Establishment and operation of residential schools were a central element of this policy, which can best be described as “cultural genocide.”6

There are 94 calls to action, many containing elements that have been repeated in demands from communities and activists and conclusions of many past inquiries and commissions. The sound of actual action has largely been drowned out by the noise of handwringing and stagnation.

At number 45 is the recommendation to reaffirm the original relationship with Indigenous peoples made by the British Crown.

It states:

“45. We call upon the Government of Canada, on behalf of all Canadians, to jointly develop with Aboriginal peoples a Royal Proclamation of Reconciliation to be issued by the Crown. The proclamation would build on the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Treaty of Niagara of 1764, and reaffirm the nation-to-nation relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Crown. The proclamation would include, but not be limited to, the following commitments:

i. Repudiate concepts used to justify European sovereignty over Indigenous lands and peoples such as the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius.

ii. Adopt and implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as the framework for reconciliation.”7

The doctrine basically meant whomever found it first, claimed it, prompting the race for every corner of North America and elsewhere, regardless of existing populations. Similarly, terra nullius or “no man’s land” supposedly left the map open to claims.

That has been used as a moral and legal argument to force Indigenous peoples to prove they were on their own land first, and even then found it difficult to assert this by the set up of the system around them.

Very little if any land was actually ceded, a point increasingly recognised by groups and some governments, such as the unanimous decision by the council of the City of Vancouver in 2014, stating the city “is on the unceded traditional territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations”.8

The call to reject did not suddenly appear with the TRC in 2015. It was a point in the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1996 nearly two decades earlier, with battles over the theologically founded concept tracing back much further.

Though previously advocating and benefiting from the doctrine for centuries, churches have made statements again in recent years. In 2010, the Anglican Church in Canada repudiated the doctrine9 as did the World Council of Churches in 2012.10 The Catholic Church in Canada repudiated the doctrine in March 2016.11

Simply rejecting the principles doesn’t turn back the clock on everything justified under them for centuries. And it remains a basis for law in the US, for example, with a decision in 2005 City Of Sherrill V Oneida Indian Nation Of NY12

Despite recent statements, there are hundreds of years of land ownership preceding them. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP),13 adopted on September 13, 2007 by the UN General Assembly, insists Indigenous peoples have the right to “redress” for land that has been “confiscated, taken, occupied, used or damaged without their free, prior and informed consent”.

The UK signed the UNDRIP in 2007 but had tempered its support at the time it didn’t apply to “historical episodes” or to “national minority groups” within its borders or territories. Karen Pierce, Britain’s deputy permanent representative to the UN in NY, added that, “United Kingdom had, however, long provided political and financial support to the socio-economic and political development of Indigenous peoples around the world.”14

If indeed there has been benevolent help from the British state, it has not hindered the argument from many Indigenous groups in Canada that, failing legal successes within North American borders, they should be able to apply directly to the British Crown, the original signatory of treaties.

British classrooms, however, taking their guidance from the state – the Crown – are clearly reminded Indigenous people who “won”.

Education Scotland’s website promotes John A Macdonald as a famous Scot in Canada.

Last year, the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, Beverley Mclachlan, stated: “The objective was to ‘take the Indian out of the child’, and thus to solve what John A Macdonald referred to as the ‘Indian problem’. ‘Indianness’ was not to be tolerated; rather it must be eliminated. In the buzz-word of the day, assimilation; in the language of the 21st century, cultural genocide.”15

If British students don’t learn about the symbols and cultures they’re making use of, with the full backing of the state, where does that leave Indigenous peoples?

Symbols or humans?

Why should the public care about how companies sell symbols to them or about government narratives in schools? For Chelsea Vowel, it’s a simple question of humanity. And it’s frustrating.

“At this point what I have to do now is convince people that we’re human, that we’re worthy of respect,” she said. “And that’s always a weak position when you have to convince other people of your humanity. And that’s what we’re often forced to do, and I really resent that.

“Why should British people care? Well, they don’t have to care because they have all the power to not care.

“But I think if people in the UK want to understand their own history a little bit more then they need to understand why these images become so pervasive – these specific ones, these Plains images in particular. And it’s an interesting history because it really is based on deliberate commercialisation. Those images were used as propaganda to get settlers out to the west.”

[Tweet “Those images were used as propaganda to get settlers out to the west””]

Posters are easy to find – in museums on both sides of the Atlantic, in antique shops and online – with the government promotion of “free land” in Canada available for a new life and the Dominion trips by sea, then across the west by train. As Ms Vowel described it, “Come look at our chiefs, come look at the bison and come look at these tipis”. The images today are the same, this time about consumption of culture rather than the land, now all taken for generations.

“People in Britain and in Canada like these images because it sort of makes them feel nostalgic,” she continued. “It’s like, ‘Ah, this is part of our history, Indians are part of our history, this is exciting’.

“But it has to go beyond the fetishistic happiness of seeing these images into the deeper, darker parts of the history.

“In coming over, in looking at that propaganda, coming over, getting land for free, the incredible displacement, the death toll that happened because the Plains were cleared, deliberately cleared, for British expansion – that has to be acknowledged.

“You can’t just take the fun bits and leave out the all the awful things that happened because those awful things that happened are still having an impact on our health and our education, our access to water, our access to human rights.

“It really comes down to if you’re a so-called civilised people that care about human rights, then you have to start looking at how you violated human rights. You have to start confronting the evils of the past and how those evils have reverberated through time. And take some responsibility for that.

“And nobody wants to do that because that’s really uncomfortable. Why should you have to account for something that was done hundreds of years before you were ever born? Except you’re still benefiting from it.

“Canada continues to have great trade relationships with Britain, our resources keep getting shipped over there, there’s still pretty strong ties between us and all of that is done without the consent of Indigenous peoples.

“I don’t know. You can’t convince people to care. They’ve just got to learn enough that they start seeing things are so wrong that they can’t avoid it anymore.”

The relationship between Canada and Britain is certainly historic, but not only limited to the past.

The Royal Bank of Scotland, profiled in Part 2 with their ad showing a child in a feathered headdress and a backyard tipi, also has a heritage section of its website. Amongst the select items promoted from their archives is a past constituent of the bank, Glyn, Mills & Co,16 and a loan invested “in the development of a whole country” of Canada. Glyn, Mills, Currie & Co was “joint London agent to the Dominion of Canada” and the Province of Canada before it since the 1830s, and was joint banker to the Grand Trunk Railway, states the website.17

Screen grab of RBS heritage website, showing loan certificate from past constituent of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), Glyn, Mills & Co. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Tomorrow asked RBS, given the bank’s direct role in expanding Canada on originally Indigenous land, what bearing did this have the ad design choices? RBS did not answer the question.

The bank was also recently named for a connection to the disputed Dakota Access Pipeline, a project which has drawn more than 200 Indigenous tribes together in protest and resulted in clashes with heavily armed police. Scottish Green Party MSP Ross Greer wrote to the party to ask about their involvement, but RBS said it was in the past, stating: “RBS has never had a banking relationship with Dakota Access LLC. RBS provided financial support to the parent company of Dakota Access LLC but have since exited the relationship.”18

Apart from banking connections, Tomorrow can reveal one of Britain’s largest pension funds hold investments in the Dakota project and others. The Strathclyde Pension Fund (SPF) hold shares in oil firm Phillips 66, which has a 25 per cent stake in the Dakota pipeline development. SPF has more than 200,000 current and past employees of local government with £17 billion in investments, including Phillips 66 shares with a market value of $3.3 million. The fund also invests in Unbridle Inc, which is behind the Northern Gateway pipeline, and TransCanada Corp, which is involved in both the Keystone XL and Energy East projects, all fiercely opposed by Indigenous groups.19

In response to questions from Tomorrow, an email statement released by SPF stated: “Strathclyde Pension Fund is a signatory to and active participant in the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment and has appointed independent monitors to ensure these principles are adhered to by its investment managers.

“The fund takes its social responsibilities seriously and is recognised as an investor showing leadership both nationally and internationally in actively engaging with the companies in which it invests, in order to challenge them to address risks and improve performance. This covers a diverse range of issues, from executive pay to environmental performance, and does include the rights of indigenous peoples.

“These particular stocks are not direct investments by the fund, but are held passively through an index tracking portfolio – which does limit the influence the fund has, in comparison to direct investments.

“However, the fund notes the concerns raised and is currently seeking further information from the portfolio manager and its responsible investment advisors.”

As well as the financial investments by the UK into North American resource extraction and development, the import of those goods continues to grow, with Canada exporting more than $12 billion worth of goods to the UK in the past year, much of it resources from the land.20

And the UK is still sending over new immigrants. The 2016 debate about the UK leaving the European Union – now known as Brexit – before and since the successful vote for it on June 23 has carried a couple key narratives.

One has been the pitch for a separate trade deal between Canada and the UK, instead of the newly signed one between Canada and the EU as a whole. But secondly, when the referendum decided in favour of leaving the EU, those who favoured remain in the UK began talking, even if only jokingly, about moving to Canada instead.

There was a move, if only in the narrative beyond practical applications, for one group to emigrate to Canada while the other group bid for commercial deals to sell to and obtain resources from Canada. But the association with Canada and comfort or liveability is based on statistics and quality of life for the majority, not those of Indigenous peoples.

“Is the Doctrine of Discovery still informing a lot of the policy decisions? Yes, absolutely,” said Ms Vowel. “I always talk about this, I say, ‘When did colonisation stop? Give me a date. Tell me when it actually stopped being a thing.’ And nobody can because it hasn’t stopped. It’s just transformed and sometimes it hasn’t even been transformed, it’s just been given a new name.

[Tweet “”When did colonisation stop? Give me a date. Tell me when it actually stopped being a thing””]

“I find the Scots and the Quebecois, they understand colonialism, they understand being under a regime of colonialism, but they can’t take it that further step and see how they themselves are complicit in it and continue to be by furthering these narratives of either they had better relationships or they were great explorers.

“Again, this is one of those situations where I sort of wish people would just be straight out, ‘Yeah, we conquered you and we took over and we won and you lost’ rather than, ‘Oh but we’re kinder and friendlier’ and deny colonialism in that way.

“If we want to get to a point where the Doctrine of Discovery isn’t at play, then we have to recognise that internally colonised or not, whether you were the British or the Irish or the Scottish or the Quebecois, everybody that has settled on these lands has had a part in colonisation and continues to colonise these lands.”

She continued: “We haven’t got to the acknowledgement of that continuing to happen, and we can’t move forward until we do. It’s going to take more nuance than just the ‘brave explorers’.

“Does it ever discuss the current impacts? You let a couple hundred years go by and you can acknowledge some of these wrongs but it’s much harder to then link what happened to how conditions are today. I think that that’s the missing link for a lot of people.

“Even if in the UK there was an acknowledgement of how outright theft of land and resources from the Americas enriched the Empire, if you get to that point, that’s a good starting point.

“What is completely different now from prior to colonisation because of that theft of land? Making those linkages is very difficult because it’s such a span of time and it’s not so clear cut.”

Of all the issues facing Indigenous peoples in North America, why does appropriation matter? Can it be separated from other challenges? Do past wrongs, represented in contemporary advertising and products, make a difference?

“I think racism is such a deeply embedded element of Canadian, North American life, and right now it seems to be that you can live in a city and people are educated in such a way that they don’t have to be friendly to you but they have to abide by society’s rules of how to get along,” said Shelley Niro.

“But at the same time, it’s obvious to me that there is a lot of deep seated racist feelings out there and it’s just beyond the Truth and Reconciliation [Commission] – that’s sort of a layer on top that they’re peeling back and saying let’s really look at these things. Because coming down to the economics of reservations, why are people on reserves so poor? And why is the education so limited? And it’s because Canada is in such a way that it’s okay. Yeah you have your reserves and you have all these other things that you’re supposed to have, but you’ll never really be part of Canadian culture and I think it’s pretty deeply embedded.

“Even those little tipis and I forget what else is on that wallpaper, I think it’s almost like scientifically placed in front of your eyes that these are just images of a nation conquered and we can do whatever we want with it.”

Is the image of nations conquered limited to schools and education in the UK? How else has the image of free, but conquered, peoples been used beyond advertising? And how has a film narrative become part of political propaganda?

PART 5: Filming freedom and fear

- Website of Chatelherault Primary, accessed most recently on November 6, 2016. ↩

- Dazzle Fancy Dress website, and Rubie’s “Indian” category. Both sites accessed most recently on November 6, 2016. Efforts have been made to remove the word “squaw” from place names in Saskatchewan, Montana, Arizona, Maine, Minnesota. Further news coverage of the Maine ban. Though it has a mixed background, many find the term deeply offensive, accessed on November 26, 2016. ↩

- Screen grab submitted to Tomorrow by a member of staff, whose identity Tomorrow is protecting under core principle 8, “be a safe harbour to the public and staff”. ↩

- “Scots and Canada: Famous Scots in Canada”, published by Education Scotland, accessed most recently on November 6, 2016. The site has since moved to the Scottish Association of Teachers of History. ↩

- “Scots and Canada: Surviving the Wild”, published by Education Scotland, accessed most recently on November 6, 2016. ↩

- “Honour the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada”, 2015. ↩

- “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action”, 2015. ↩

- “Motion on Notice: Protocol to Acknowledge First Nations Unceded Traditional Territory”, regular council meeting of June 24, 2014, City of Vancouver. ↩

- The General Synod repudiated it, but repairing the mistakes caused by it has been less forthcoming. Accessed on November 6, 2016. ↩

- “Statement on the doctrine of discovery and its enduring impact on Indigenous peoples”, February 12, 2012. Accessed most recently on December 4, 2016. ↩

- “Catholic church in Canada repudiates ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ and ‘terra nulls’”, Two Row Times, March 30, 2016, accessed most recently on December 4, 2016. ↩

- City of Sherrill V Oneida Indian Nation of NY (03-855) 544 U.S. 197 (2005), Supreme Court of the United States, accessed on November 6, 2016. A website for a conference on the doctrine in law in 2014 can be found here, accessed most recently on November 6, 2016. ↩

- UNDRIP. ↩

- GA/10612, General Assembly, 107th and 108th meetings, accessed most recently November 6, 2016. ↩

- “Reconciling Unity and Diversity in the Modern Era: Tolerance and Intolerance”, remarks of the Rt Hon Beverley Mclachlan, chief justice of Canada, delivered May 28, 2015. Emphasis from the speech itself. PDF of speech as delivered. ↩

- “Glen, Mills & Co”, RBS heritage hub, accessed most recently on November 12, 2016. ↩

- “Object 55 – loan certificate, 1880”, RBS heritage hub, accessed most recently on November 12, 2016. ↩

- “Profile: Dakota oil pipeline”, The National, published November 3, 2016, accessed most recently on November 12, 2016. ↩

- Strathclyde Pension Fund (SPF) assets to June 30, 2015.. ↩

- Canadian International Merchandise Trade Database, Statistics Canada, figures for year to September 2016, accessed most recently on December 4, 2016. ↩