Is New Brunswick unravelling?

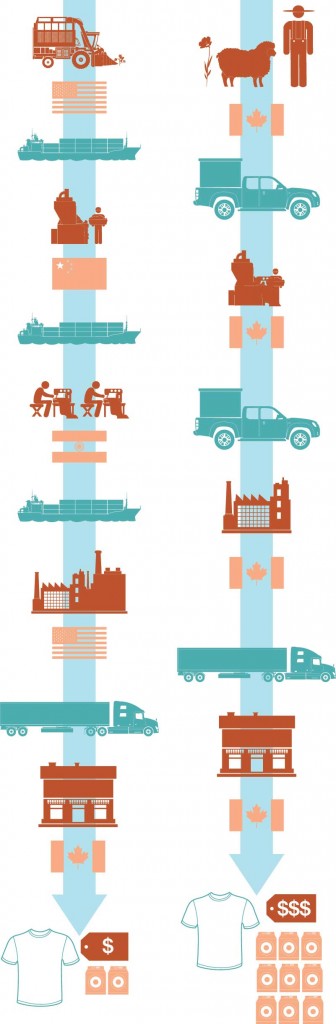

What are we wearing, by Jason Skinner, artist in residence. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Ask about a textile economy in New Brunswick and people refer to the Atlantic Yarns case, even if they don’t know the name. One economist cited it as proof the industry wouldn’t work in New Brunswick. John Little, of Briggs & Little, referred to the province bringing in people for a synthetic textile mill and “they’ve sort of lasted as long as grants or assistance did, and then they just seem to be gone”.

There is an economic problem in the province. Compared constantly, and unfavourably, to resource-rich powerhouses Alberta and Saskatchewan, the provinces are draining talent from New Brunswick and across the Maritimes while government deficits continue, debt climbs and one in 10 are unemployed. Some have suggested it is heading for bankruptcy.1

The solution, from the current government, has been to propose felling more trees from what is known as Crown land in a deal with the Irving corporation, the province’s dominant firm. Fracking or shale gas exploration is the other supposed growth market, but one so controversial even economists won’t include it in their outlooks for New Brunswick. But the world demands natural resources, and that’s where the money is. Shouldn’t the province deliver? Is it a lost cause if it doesn’t?

‘Out of their hands’

The New Brunswick department of economic development did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. But the economists who rate and rank the province did.

Robert Kavcic is a senior economist with the Bank of Montreal2 and said the strength of the Canadian dollar up until a year ago, and the weakness of the US economy, hurt exports and manufacturing. The reversal of both those trends will now be in Canada’s, and New Brunswick’s favour.

But the province’s ongoing deficit and growing debt is restricting government investment. Mr Kavcic said that was likely to continue.

“You’re seeing very sluggish if not negative population growth, and part of that is because of a pretty significant movement of migrants from not only New Brunswick but basically all of Atlantic Canada to western Canada,” he said.

“Depending on what’s happening with oil prices, Alberta will either be at the top of the pack or near the bottom. It’s not necessarily saying that one is better than the other or policy makers are doing better in Alberta than in New Brunswick. It’s just the nature of the game is a lot different. And right now, with higher oil prices and a strong Canadian dollar, that’s playing right into Alberta’s hands.

“The flip side is it’s playing heavily against pretty much anywhere from Ontario east. And Atlantic Canada a bit of an added challenge on the population side because you’re just not getting enough immigration that you’re getting in somewhere like Ontario.”

What can New Brunswick do? Not much.

“A lot of it is just the macroeconomic environment that’s pretty well out of their hands,” said Mr Kavcic by phone. “On the policy side, just balancing the budget and getting a handle on longer-term finances is probably necessary at this point.

“We’re going into a slower long-term growth environment. A bit of a structural deficit in New Brunswick and most of Atlantic Canada needs to be addressed. Once that gets addressed, then we can talk about some other measures like on the tax side, because the tax side is relatively uncompetitive, in provinces like New Brunswick [and] Nova Scotia versus the rest of Canada.

“But at this point they can’t really do anything about that because they’ve got that deficit to deal with. If the US economy picks up and the Canadian dollar falls, that’s going to be a boost to revenues and should help to close that budget gap. But we’re still a few years away from that.”

Is a slow-growth economy better or safer? Mr Kavcic said New Brunswick could do with more diversity through developing resources, just as Alberta could do with more manufacturing or other areas of the economy, where it currently “runs entirely on oil”.

“The one thing you can take away from what the private sector’s saying right is that the conditions are probably going to get a little bit better over the next two years, not worse,” he said.

“At the end of the day, the choice to move out to Alberta when there obviously are jobs, or higher paying jobs, it’s a personal choice.”

Marie Christine Bernard is the assistant director of the provincial forecast service at the Conference Board of Canada. The board published a report in April on the long-term outlook for New Brunswick and other provinces, projecting as far ahead as 2035.3

Marie Christine Bernard is the assistant director of the provincial forecast service at the Conference Board of Canada. The board published a report in April on the long-term outlook for New Brunswick and other provinces, projecting as far ahead as 2035.3

The Conference Board monitors GDP, output by industry, housing, demographics, trade and market conditions, and other factors, producing five-year forecasts.

A spokesman for the Conference Board said reporters aren’t allowed to see the 20-year forecast, but the public summary is bluntly negative, saying real GDP growth will average 1.2 per cent annually, “good enough for only ninth place among the 10 provinces”. It predicts population decline, slowing growth in potential output and limited revenue-generating capacity.

Do the negative reports hurt business investment in the province? Are the economists making things worse?

Ms Bernard told Tomorrow that the weak economy, lack of big capital investment and low consumer demand has held the province back. Though the Conference Board compares and ranks provinces, Ms Bernard could not say whether that would, in turn, put off investment in a province, but admitted the long-term forecast “could be one of the factors”.

She said: “The long term we don’t discuss with reporters. It’s impossible not to judge against Alberta. The fact that Alberta is doing very well is not taking anything away from New Brunswick. You look at the economic potential of the province.”

The forestry investment – controversial across much of the province – was cited as a specific boost to industry and jobs. But Ms Bernard said a report on the short-term forecast identified a problem with productivity looking at output and the number of hours worked.

Ms Bernard added: “New Brunswick got a C in productivity – it’s not much different than in the rest of Canada. We don’t invest a lot in innovation – [we] need to invest more in machinery and equipment. That’s a problem for productivity compared to the United States.”

“Clearly,” added Mr Kavcic, “if somebody’s at the bottom of the pack in all these reports, it’s going to make investment decisions a little more tentative in that part of the country.

“But I don’t know if the reports specifically are responsible for that. Any thorough business would look at the labour market and regional finances and stuff on their own before they make an investment. I don’t know if it’s the function of the report or the function of the economic environment.”

Where the money goes

New Brunswick does offer a comparatively good bang for your buck on investments such as property, with the Canadian Real Estate Association saying the national average price of $400,000 would buy you double the space in Saint John compared to Toronto or Vancouver and easily more than in resource-rich Alberta or Saskatchewan. But your money would not go as far as in comparatively nearby St John’s, Charlottetown or Halifax.4

And transport, as businesses reported in Part 1, is a major problem for costs and accessibility. The unemployment rate, as of August 20145 was 8.7 per cent in New Brunswick, compared to 7 per cent in Canada overall and 4.9 per cent in Alberta and 4.2 per cent in Saskatchewan.

Without jobs, what is the state of the middle class?

The median income in Canada may have reportedly passed that of the US6, though politicians continue to argue about whether the middle class is doing well or hurting. Regardless, the demographics will be different within New Brunswick with the higher unemployment rate and shrinking population. Marketing products such as textiles solely to the middle class, and tourists, was an approach that didn’t work for Mary Black and Nova Scotia, as we reported in Part 2.

And while retail remains the biggest employer, more than manufacturing, healthcare or construction, according Statistics Canada,7 investment is retail of the cheap goods. Wal-Mart announced in February spending of $1/2 billion to expand in Canada.8 That offers cheaper clothing options and low wages for workers, compared to what New Brunswick textile producers might create for inconsistent income.

Somebody could choose to make textiles for a living, but not if consumers choose the Wal-Mart alternatives. And if all consumers opt for cheap products from overseas, who would choose to create local alternatives? The economics require both supply and demand.

But demand might be changing.

Pierre Cléroux is the vice-president of research and chief economist at the Business Development Bank of Canada, which published a report on consumer trends in October 2013, found “Made in Canada” to be one of five major driving forces for consumers.9

The survey found it was even more important in the Atlantic provinces. When asked, “Have you made a specific effort to buy a product that was made in Canada?”, 45 per cent of Canadians said yes. In Atlantic Canada, the figure was 57 per cent.

And when asked if buying locally made products was important in making a decision, 39 per cent of Canadians said it was, compared to 45 per cent on the east coast.

Mr Cléroux said it was about creating demand and offering the choice.

“The buy locally movement is stronger in the Atlantic provinces,” he said. “Consumers value locally-made products, they value products that are good for your health. So it’s important for businesses to understand what consumers put value on, first to offer the right products and also to market your product with those communication techniques.

“For example, if you look at the marketing campaign of the milk producer, you will see that they advertise themselves as 100 per cent Canadian milk. And the milk in Canada has always been Canadian – we don’t import milk.

“But they realised that people put value on locally made products or Canadian products. So now they market themselves as 100 per cent Canadian milk. The milk is the same – the milk is not different than 10 years ago. But they understand now that people put value on that.”

Mr Cléroux said major clothing and furniture brands were offering Canadian options at the till and, combined with marketing more to the web, were changing how consumers make choices. And consumers are willing to pay more for local.

He said: “People would prefer to buy a Canadian product, but there’s a limit at the price difference that they are willing to pay. We estimate that the price difference is between 10 to 15 per cent. It’s a limit in terms of the gap of the price they can afford.”

Illustration by Artist in Residence Jason Skinner. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Kelly Drennan is the founding executive director of Toronto-based Fashion Takes Action10 and said the trend in the next 10 years will be toward more local manufacturing, whether for finished production or a hybrid of offshore and local work.

She said the organisation’s definition of sustainability is quite broad and could include eco-friendly fabrics such as Tencel, organic cotton or hemp, or recycled fibres, “vintage” or second-hand clothes, fair trade, local, natural dyes and “slow fashion”.

“Canadian-made garments and textiles mean there is a reduction in environmental footprint because there is less shipping involved,” she explained by email. “It also positively impacts the economy.

“If there is still a market here in Canada for Canadian-made textiles, then that plus the benefit to the local economy would offset the environmental impact of shipping. The reality is that exporting/importing will not be done with. There are things we rely on from overseas, and likewise other countries rely on our exports.”

Ms Drennan said there is a cost per wear to clothing. Using the example of a $40 fast fashion dress from H&M versus an organic cotton version made locally for $100:

$40 trendy dress, cheaply made – the number of wears over an average of two seasons = 20. Cost per wear = $2

$100 seasonless well-made dress – the number of wears over 6 years = 200. Cost per wear = $0.50

She said she is still wearing a pair of locally made pants that are now 12 years old, and they work year round, and she estimated they have had 600 wears for an original cost of $300. A pair she bought at Club Monaco five years ago cost $90 but were too trendy and have only been worn around 30 times, making a cost per wear of $3.

“Buyers are not asking the right – or important – questions,” she continued. “This is mainly because they don’t realise the implications of fabric made offshore – in most cases but not all – or the environmental damage that the textile industry creates each year, such as landfill, polluting fresh water etc.

“Consumers need to stop and think about their clothing purchases. If something is dirt cheap, there is likely a human or environmental cost – the true cost of fashion. There is no way that a garment worker was paid fair wages, or that a company was responsibly disposing of its waste (including toxic waste water) if a garment costs $5 or $10. We need to invest in our wardrobe and buy quality pieces that are going to last us, not only in terms of durability but also in terms of not being overly trendy. Buying seasonless classic pieces is a much better use of our money and in the long term will be more economical.”

Ms Drennan insisted that a growing number of people did care and were asking questions, but not to the “tipping point” required for meaningful change.

“There is a myth that being a sustainable consumer costs more and is exclusive to only those with disposable income,” she said. “In fact the opposite is true if you look back a couple of generations ago, when times were tough our relatives were being sustainable by reusing and repurposing not just clothing but other household items.”

Businesses aren’t asking questions – or answering them

If most consumers don’t ask where their clothing comes from, neither do the shops selling fabric to make clothing.

Calls to the three New Brunswick outlets of Fabricville11 – with 24 stores from Quebec east – to ask if they had material woven in Canada yielded:

Saint John: “We wouldn’t know – they don’t give us the details when they ship them from the main warehouse.”

Moncton: “No. Most of our fabrics come from India.”

Fredericton: “I couldn’t answer. From around the world.”

Tomorrow also asked Ryerson University’s school of fashion12, one of the nation’s leading centres and in Canada’s biggest city of Toronto, where their textiles came from.

Initially, Professor Sandra Tullio-Pow at the school directed the question to the Canadian Apparel Federation but later said the only fabric they regularly order is muslin, a factory grade cotton used to make prototype garment designs. She said the muslin is from India.

That basic detail took several queries and more than a month to obtain, hinting at the reluctance of the fashion trade to discuss their methods and materials. Similarly multiple emails and phone calls to Tristan Style in Montreal 13 – which sells “Made in Canada” garments – and to Heritage Textiles in Moncton went unanswered.14

New Brunswick’s biggest and most powerful firm is JD Irving Ltd,15 set to benefit most from any west-east pipeline for Alberta bitumen sands, set to benefit most from proposed increases to forestry in New Brunswick,16 and backed by a monopoly on all English daily and most weekly newspapers. Amongst its subsidiaries is Chandler, producing much of the outerwear and branded wear for companies across the east coast.17

New Brunswick’s biggest and most powerful firm is JD Irving Ltd,15 set to benefit most from any west-east pipeline for Alberta bitumen sands, set to benefit most from proposed increases to forestry in New Brunswick,16 and backed by a monopoly on all English daily and most weekly newspapers. Amongst its subsidiaries is Chandler, producing much of the outerwear and branded wear for companies across the east coast.17

Mary Keith, vice-president of communications for JD Irving, said they would not reveal the profitability of their apparel division, but said they were unaware of any in-province supplier that could meet the needs of Irving or Chandler. Chandler’s manufacturing facility, specialising in outerwear and custom fire retardant gear, is in Newfoundland.

Ms Keith said in an email statement: “Chandler offers many Canadian manufactured products, and sells Canadian manufactured products as often as competitively possible. Many of our main suppliers in both the apparel and promotional fields are providing products manufactured in Canada. One of our largest suppliers of work wear manufactures almost exclusively in Canada.

“Our fabric suppliers are Canadian companies that purchase grey goods – from textile mills – in the United States and then bring them into Canada to prepare them as finished fabrics, i.e. dying or coating of fabrics.”

Illustration by Artist in Residence Jason Skinner. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Would local really work?

So consumers and businesses have money to spend on textiles, the historic knowledge is there to produce them, and as we will report in Part 4, the land and expertise exists to grow the raw material.

But New Brunswick’s economy remains driven by natural resources and, particularly, Irving. What economy and environment does the region want?

Alex McIntosh, from the Centre for Sustainable Fashion in London, said products don’t necessarily need to be expensive simply because they’re produced with environmental impact taken into account. But certain textiles are more expensive to produce.

“If you are working in a labour market that is expensive and you want to work locally,” he explained, “you can sell a certain quality and a certain finish and a really strong narrative story. Then you deliver a product at a price that is not going to be easily accessible for everyone, but it’s not about easily accessible for everyone. It’s about an aspirational, desirable product with a strong story about localism embedded in it. Which is a powerful message – it’s one of the few sustainability messages I think that has really had some legs in the last few years in the UK, but I think globally as well.

“If you’re interested in democratic product that is readily available to everyone, you’re not going to be able to deliver that. So you have to be thinking about what kind of market is there. What do people want?

“If you’re talking about changing the whole domestic market, then there’s a massive shift in consumer thinking and behaviour and a kind of shift back to the kind of attitude of things being investment piece and stuff that you actually save up to be able to acquire. And it’s a big mindset shift. And when you’re talking about a particular youth generation that have grown up with fashion being accessible at all times in every place, you’ve got a tricky task at hand.”

Mr McIntosh said there were few examples of fully integrated, larger scale supply chains – from farm to finished product. But sometimes smaller options, focusing on localism, can work.

He said American Apparel is an example of local manufacturing, while not sourcing the raw material locally.

“They manage to counter that with being a brand that is very, sort of, edgy and fast fashion in the rest of their approach to things,” he said. “I personally think it’s a hideous brand, but I can’t deny their success. They somehow make that local agenda sit with selling very cheap, quite nasty product – but that’s the market they’re going for. And to me that’s demonstrative of the fact that it doesn’t always have to be about quality and finish and wonderfully beautifully manufactured product in order for that message to fly.

“But it’s still not even close to being a fully integrated thing. They’re not sourcing their yarns in California.”

Mr McIntosh said there is an awareness of how fashion is produced and that it’s not a great system currently – but that understanding doesn’t really extend to the general populace, or, as we have reported earlier, the businesses in New Brunswick at the moment.

“It’s a very long way off genuinely changing people’s behaviour,” he acknowledged. “I would love to say that in the last 10 years of working in fashion and sustainability I had seen a tremendous shift in terms of attitudes and investment in clothing. There has been a shift but I don’t think it’s been as dramatic as sometimes people would like to make it sound.

“There’s also really big dangers that sustainability as a concept is being owned by corporations and being translated into corporate language and becoming about corporate social responsibility and not really about individual commitment. And it takes that individual commitment, because a corporate social responsibility just doesn’t work without that. It’s not solely a production problem; it’s an attitude problem.

“All you’re going to do if you change the production system is you incrementally make things a bit better. But because people continue to think that they can consume in whatever way they wish, that increment is completely cancelled out by the increase in people’s consumption.” Mr McIntosh said the 2010 consumption of textiles went up by 45 per cent globally, offsetting any potential improvement in environmental management systems. Nothing can counteract that growth.

“Things are getting better, but they’re also getting worse,” he added. “For me, as a person, there’s a massive amount of work to be done around the kind of psychology of consumerism and how we really start to dig into that and change people’s behaviour.”

As we will report in Part 4 looking at the land in New Brunswick and its potential, and current waste, much of the technology is missing for flax and linen production, as is the case in Europe. Mr McIntosh said for a human-resource heavy textile industry on linen production, it makes it hard for make something financially viable against cheap and efficient competition in East Asia.

“I don’t necessarily think that’s good, but it’s the reality,” he said.

In the realm of textiles, the concept of doing things “more efficiently” is nearly impossible, with machines having proved more than a century ago to put textile workers out of employment. So would a rise in that industry in the province be useless as far as economists comparing provinces are concerned?

New Brunswick and Canada, said Mr McIntosh, is a very developed economy with wage expectation relatively high, set against profitability from most textile production being relatively low. That clashes with the “economic growth” argument of the economists rating and ranking New Brunswick.

“If you work on the assumption that the intention is to make an economy grow in conventional terms, then I’d be amazed if textiles is the way to go,” admitted Mr McIntosh. “If that’s not the end goal, then I think you’ve got a really interesting dialogue to be had.

“And I think it’s a really good opportunity to have that conversation about whether, actually, this might be a good example of a post-growth economy, an economy that might be self-sufficient and efficient but doesn’t necessarily have massive growth potential.”

For New Brunswick can choose a different kind of economy, it needs the land – and the land is hurting.

Part 4 – Connect to the land and the people who live with it

- Past reports have warned the province is facing bankruptcy. ↩

- Robert Kavcic. ↩

- Press release on NB’s “D” grade and link to long-term forecast report, only available to subscribers. ↩

- CBC graphic comparing house prices, based on CREA March 2014 figures. ↩

- Latest employment stats here. Image of August 2014 figures here. ↩

- New York Times article on the middle class in Canada. ↩

- StatsCan figures on employment by sector. ↩

- Reported Wal-Mart investment. ↩

- Made in Canada report by BDC. ↩

- Fashion Takes Action. ↩

- Fabricville. ↩

- Ryerson University’s School of Fashion. ↩

- Tristan Style. ↩

- Heritage Textiles. ↩

- JD Irving Ltd. ↩

- Forestry proposals. ↩

- Chandler Sales. ↩