Connect to the land and the people who live with it

What are we wearing, by Jason Skinner, artist in residence. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

“I was just a small child – couldn’t have been more than 10 or 11 – stood on the veranda and watched my father’s face when hail wiped out his potato crop for the year,” recounted Betty Brown. “And he just said, ‘Enough of that’ and cut his acreage down to just a few acres and built a piece on the barn and started milking more cows.”

Ms Brown is stepping down as a director on the Canadian board of the National Farmers Union.1 As well as being a past executive director for the union and past president of the NB Farm Women’s Organisation, she has a small herd of 38 cows. And she knows farmers are hurting.

Speaking from her Summerfield farm, Ms Brown told Tomorrow that with the local auction barn gone, the next nearest is 45 minutes, transport costs make farm finances even harder. Driving the family car has gone from costing $30 a week to $70. And fuel costs get added to fertiliser, equipment and anything else connected to farm life.

Local purchasing power was not enough on its own to keep farmers afloat and Ms Brown said she had branched into “value added” products, such as baking or cooking meet at farmers’ markets for sale. And some members of her family work off farm to bring in income.

“It’s really tough and it’s not the way it should be that a farmer has to work off the farm to feed their family,” she explained. “That’s the way it’s always been here – one of us has always worked off the farm or we had a small sideline trucking business and you’ll see that on 95 per cent of the farms.”

With farms facing financial strains, more are giving up as small farms get swallowed into ever larger farms with more financial clout, less flexibility and different risks if they go under. And supplier firms are also merging, driving up costs. Even small bits of pasture ground are getting used up for corn and soy beans because of their high prices.

“I see the struggle,” said the mother of three. “We’re losing farmers here everyday.

“They kept telling us big is better, big is better. And I don’t see it. I think we need the small family farm. And that’s what I’m seeing coming back – the young people buy or rent five acres and they’re working by hand, sometimes without even a tractor. They’re producing food. And it’s the most important occupation there is – producing food. Because you can live without a lot of things. You cannot live without food.”

Ms Brown said she tried to get the provincial government to put signs on the four-lane highway for every exit with a farmers’ market, and they wouldn’t do it. Similarly, she condemned the policies of the federal government, particularly ending the Canadian Wheat Board’s monopoly in 2012.2

Ms Brown said she tried to get the provincial government to put signs on the four-lane highway for every exit with a farmers’ market, and they wouldn’t do it. Similarly, she condemned the policies of the federal government, particularly ending the Canadian Wheat Board’s monopoly in 2012.2

“Until politicians get hungry, we’re not going to have the support we need for agriculture. If you’re a big company and you’re involved in agriculture, that’s the ones they talk to.”

The state of agriculture is not a uniform picture, with shades of success and struggle in different sectors and varied regions.

Jennifer MacDonald is president of the Agricultural Alliance of New Brunswick.3 Speaking by phone from the field of her farm just outside of Bouctouche, she said fewer people are getting into farming and more are leaving. Sometimes there is nobody to take over your farm or the operation, some are hit by land costs, and others lose out to urban sprawl.

New Brunswick has seen an increase in urban populations, but rural was a higher percentage until 1966 and the 1980s and 1990s, and even today remains split 53/48.4 But within that clash of urban and rural is the start of renewed interest in agriculture, particularly with smaller plots of land.

“There’s a bigger interest in growing your own food or supplying a small community, and that’s where we’re seeing the biggest growth,” said Ms MacDonald.

“Larger operations are a little more self-sufficient and sustaining, however, they’re facing more challenges with finding labour. And finding labour is the biggest challenge of the larger operations.

“You’re kind of caught between a rock and a hard place. Do you stay small enough to do it all yourself? Do you stay a medium size where you only need somebody periodically? Or do you go large where you need somebody all the time or more than one and face those challenges?”

New Brunswick had 33,500 unemployed residents in August, according to StatsCan5 but little education about agriculture as an option. And even then, said Ms MacDonald, many could not or would not consider working on a farm.

“It takes a special kind of attitude to work on a farm,” she admitted. “You hire for attitude and train for skill.

“In the urban areas a lot of people don’t necessarily want to travel to a farm because of the hours and the workload. There’s a lot of other reasons too. There are some people who are unemployed who would be willing to work on a farm but they have no place to leave their children or they have no transportation and where they live in an urban centre they rely on the transit system.”

Ms MacDonald said government departments were disconnected, but that there was some slow progress. The problem was a failure to learn from the past and a need for the agriculture community to be more vocal in contributing to the education and wellbeing of New Brunswick.

Ms MacDonald said 80 per cent of the effort needed to be on education, 20 per cent on marketing.

The next generation

Quite apart from consumer education, there will only be a next generation of farmers if they have the education and training. There are now just two high schools teaching agriculture, and in 2012, the provincial government made the class an elective, instead of counting as a science credit towards a high school diploma.

Yet the department of agriculture in the same government offers grants and assistance for new farmers and expansion of agriculture, if individuals have the required agriculture education. University level training is offered outside the province and any inspiration to try it would come from school.

The department of education did not reply to a request for comment on the changes to the credit or educating for the future of agriculture in the province.

Daniel Reicker took over teaching agriculture at Sussex Regional High School6 four years ago, one of only 53 teachers there with any agriculture background. His own father runs a vegetable farm in the area, one dominated by agriculture and home to Legacy Lane mills, as reported in Part 1.

“What we are trying to do is set up students for success,” he said. “More so now because these students are not getting the science credit.

“We need to whet their appetite, we need them to see what’s going on in agriculture – there are more opportunities now and more need. There will always be a job here.”

Out of 29 students who took the class in the last two years, only about three or four were from farming backgrounds and just four moved on to further education in agriculture.

“People don’t know where their food is coming from because we are not teaching it,” said Mr Reicker, who said he would buy farmland himself if he could meet the steep price. “Our whole society has said there’s no future in farming. Get a government job, get something that’s going to pay a pension versus having to budget over the year.”

Mr Reicker admitted that textiles and the related agriculture is not part of his current course, but the curriculum would allow for it.

“I know New Brunswick can be successful in agriculture,” he said. “It’s pinpointing the various departments or the various needs of the market, and pinpointing what our land does best. We have the perfect opportunity to excel.

“The curriculum is open to whatever we need to make agriculture more attractive to new students. I do know if we had the passion and a little bit of support, there must be a way to be successful.”

Back to the land

Even if there was more interest sparked in schools and the wider public, Jennifer MacDonald said only 2.5 per cent of the province has the topsoil available for agriculture. It needed to be preserved and house building on it halted under a province-wide approach, not the inconsistencies of local and regional planning.

“If we had a land-use policy,” she said, “then that would circumnavigate a lot of these issues. And with the land use policy then we would have a Topsoil Preservation Act [with] teeth. This would limit or eliminate the ability of people to strip top soil and move it to lawns in urban jurisdictions.”

But actually, nobody knows how much farmland is active or unused, and nobody knows where it all is to save it.

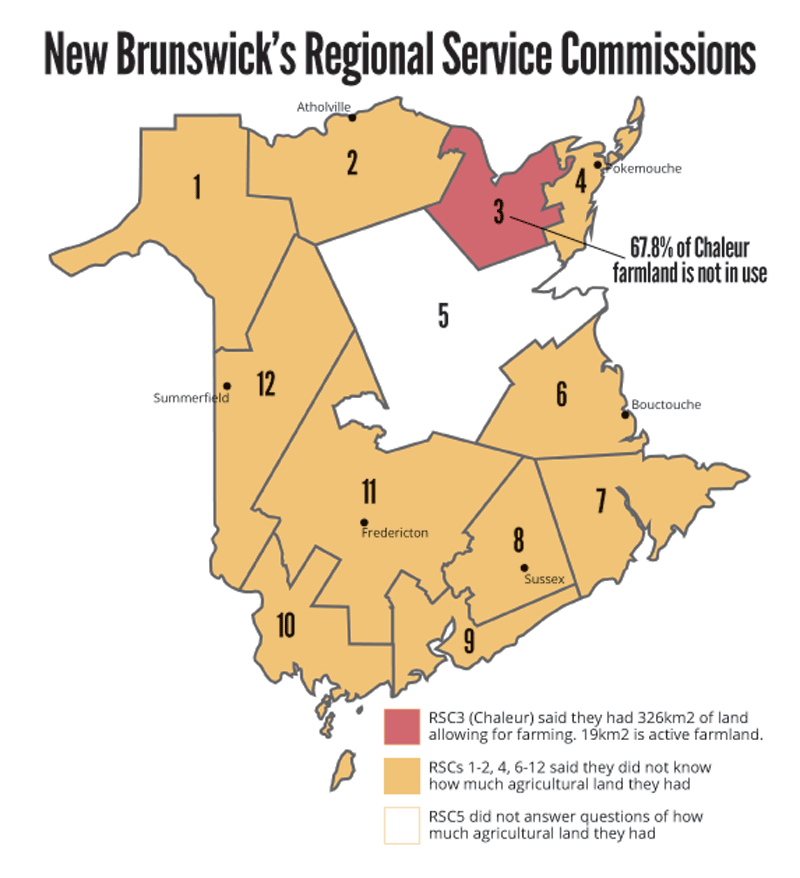

Just one of the 12 Regional Service Districts, put in charge of planning as of January 1, 2013, has mapped agricultural land and how much is currently in use. Tomorrow contacted all 12 and most said they were awaiting local municipalities telling them of their land use – with no deadline of when that information is needed. Others directed us to the provincial government’s agriculture department, who in turn admitted they have just one statistician and rely on the federal Statistics Canada for current agriculture figures.7

The Finn Report in 20088 recommended the provincial government issue “planning statements” under the Community Planning Act, but none of the listed issues mention top soil preservation or agriculture. These statements would be reflected down through regional and then local plans.

Yet “holistic” regional service plans are meant to, “Serve as a social and economic development strategy for the region in accordance with sustainable development principles” and “Plan and coordinate the major land uses and associated activities in the region”.

And it states plans should cover, “Policies affecting the use of land in the region; a) identification of urban and rural development boundaries and propose location of residential, commercial and service locations in accordance with sustainable development principles; b) identification of agricultural lands and mineral resources such as peat moss, granulate, gravel, sand, etc, and policies concerning their existing and potential uses” and would be compulsory for municipalities and others in the area.

What has resulted is much more complex.

Karen Neville is the planning director of Regional Service Commission 8 (RSC8), covering land stretching north east from Hampton towards Sussex and on towards Moncton.

She explained that because much of the land in the province is considered “unincorporated”, much of it has no planning or zoning at all. That land is legislated to be part of the RSC and receive planning services from it. Municipalities can also get planning services from the RSC, but aren’t legislated to.

Two villages in RSC8 – Sussex Corner and Norton – have “rural” zones where agriculture is permitted, but are not defined as specific agriculture zones.

Two larger towns – Sussex and Hampton – have their own planning services and don’t use those of RSC8.

Within an RSC are local service districts (LSDs), sometimes still referred to as parishes, which can have their own local plans, as can municipalities such as towns or villages.

Only one LSD, out of 14, has a land use plan, which has both an agricultural zone and a rural zone that permits agricultural operations, said Ms Neville.

And three of those LSDs adjoin but are separate to the towns of Hampton and Sussex and village of Norton, all with separate planning rules and designations.

The rest of the area defined as RSC8 has no formal land use planning.

Ms Neville said: “Historically this region is an agricultural community, but over the past number of years the number of farms have been on the decline.

“The previous planning commission which was responsible for this region was very supportive the protection of agricultural land.

“At this time many our unincorporated communities do not want a land use plan/rural plan. RSC8 is responsible for developing land use plans for communities, but only do so when the community expresses an interest. The content of those land use plans would be driven by community interest. If the community expressed the need to protect agricultural land we would ensure that the land use plan would do so.”

She added: “Since we have only been establish for a year and a half we are still developing how best to deliver the other mandated services.”

The RSCs have not yet pursued regional planning, as originally laid out in the Finn Report, because they are awaiting fresh legislation.

Gérard Belliveau, executive director of Southeast Regional Service Commission (formerly called RSC7) and himself an advisor to the Finn Report, said both this and the Commission on Land Use and the Rural Environment (CLURE) in 1993 recommended the provincial government adopt land use policies. What came about were “broad policies. . .without legislative clout”, said Mr Belliveau by email. He added: “The RSC have been established by the regional plan format and provincial land use policies have yet to materialise.”

Mr Belliveau said they were working with groups such as the Westmorland Albert Food Security Action Group to find more agricultural opportunities. And while most regions would be in favour of more agriculture, a provincial land use policy on agriculture, under the Community Planning Act, would enable “regional and local communities to plan and respond to agriculture production needs, including flax and livestock for wool production. At this point in time, the department of agriculture lays the groundwork on a case-by-case basis without a comprehensive provincial land use policy.”

Jack Keir, executive director of Fundy Regional Service Commission (RSC9), said getting community plans from each community “can be somewhat like pulling teeth, trying to convince rural NB they should have a land use plan telling them what they can do with their land”.

Only the Chaleur region (RSC3),9 covering 3,307km2 of land, was able to answer Tomorrow’s questions about current agricultural land use. Excluding the city of Bathurst, which has its own zoning rules, the other nine municipalities have 455km2 of zoned land, and 326km2 of that allows for farming.

Using information from the Farm Land Identification Program (FLIP),10 a provincial scheme to provide tax credits to help protect farmland, RSC3 said they had 337 properties covering 59km2.

Going one step further, RSC3 used 2007 aerial photos of the region, tracing out fields and farms by hand, said planning technician Mariette Hachey-Boudreau. Comparing this data with FLIP data they found only 19km2 of 59km2 is active farms, meaning 40km2 of farmland, or 67.8 per cent, is not currently in use.

What is most important about this 40km2 of unused farmland is that the Chaleur region is next to RSC2 and RSC4, including the communities of Atholville and Pokemouche respectively, homes to the Atlantic Yarns and Atlantic Fine Yarns factories that we reported on in Part 2. They were set up at a cost to taxpayers of millions to process fibre from overseas, ultimately closing down when land potentially capable of producing raw material for processing was just a few kilometres away. The taxpayer money was invested, then written off, weaving equipment sold off, all while agricultural land and skilled labour went to waste and unemployment went up.

Whose land is it anyway?

Quite apart from the preservation of topsoil and administrative ignorance of where agriculture land might be, the land belongs to somebody else.

Maliseet elder Alma Brooks from St Mary’s First Nation,11 on the banks of the St John River (Wulustuk in Maliseet), has been a vocal opponent of shale gas development in the province. She said many people looking at alternatives to shale gas, mining and the extractive industries. And it was a concern for both indigenous and non-indigenous peoples.

“A lot of our land has been destroyed as the forest goes,” she said. “The Irving empire has been in there, stealing our resources for several generations. All of that would have to stop to have some kind of alternative.

“These companies that are doing this, they run the government. They are the government.

“When [settlers] first came to these shores, there was a paradise here, and it was a paradise because our people looked after the land. We worshipped the land we walked on. We didn’t manage it, but we didn’t forget to say thank you either. So there’s a whole different ideology about the land and the water, the natural world.”

The recent Supreme Court decision about the Tsilhqot’in First Nation in British Columbia12 could have profound effects on land disputes across the country, not only over clashes over public or Crown Land, but also private land.

Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, leading the unanimous ruling, said indigenous title to land “flows from occupation in the sense of regular and exclusive use of land … Occupation sufficient to ground aboriginal title is not confined to specific sites of settlement, but extends to tracts of land that were regularly used for hunting, fishing or otherwise exploiting resources and over which the group had exercised effective control at the time of assertion of European sovereignty”.

New Brunswick is part of the vast territory including Nova Scotia, parts of Quebec and Maine that define the traditional Wabanaki Confederacy, made up of the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki and Penobscot peoples. There still exist traditional grand councils and are places where people need to start talking about how the territory is being used and will be used in future.

“The Tsilhqot’in case says that wherever the land has not been seeded, then whenever the land has not been officially surrendered, it still belongs to our people. It’s still Wabanaki territory,” said Ms Brooks.

“Private land is still our land, it’s really occupied territory. In the Tsilhqot’in case, it did not include the private property because they were looking for the support of the non-native citizens, so they’re scared that they’re going to lose their farms or lose this or lose that. So Tsilhqot’in-ans said, ‘Well, we’ll just include in our court case land that’s not occupied’. And the other would just be unresolved issue that would have to care of some time later.

“I really think a dialogue needs to happen about ways to use the land that is not going to be destructive to waters and forest and how to restore the damage that’s been done, and yet be able to produce jobs for people.

“It doesn’t matter who is using the land, they still have to have the consent of our people if they’re going to use our land. That would have to happen. Does it matter to me who’s stealing my resources, whether it’s Irving or whether it’s someone else?”

Ms Brooks said the homestead farmers had been put out of business by larger firms that had less concern for the land.

“The small farmer, who cared for the land and who took the pains of looking after it properly, a lot of them have got so discouraged because they couldn’t make a living because of these big big companies.

“What has to happen is we have to really reconnect ourselves spiritually to the land again.

“People have to see something sacred in the life of others. Things here, right here on earth.

“Because we can’t destroy if we believe that it’s sacred. And that’s the connection that our people had and still have, some of us, with the land. That’s why our people didn’t sell the land, that’s why our people didn’t surrender the land, because they knew that we hold the key to the survival of life on this planet, if people will wake up. I just hope that they don’t wake up too late.

“People need to demand change, and if we don’t do that, it won’t even be safe to have sheep or anything else.”

Illustration by Artist in Residence Jason Skinner. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

The opportunities

If topsoil can be protected and opportunities for new farms established with communities and indigenous title holders, there is potential in New Brunswick.

The province’s department of agriculture already promotes localism for food, though not textiles, which is considered crafts and part of the department of tourism, heritage and culture.13 Marketing is a key element of the future potential, but who is responsible?

The New Brunswick department of tourism, heritage and culture said crafts and artisan support, as part of “culture” for the past decade, was part of the economic development department. “The economic value of this sector is recognised,” said Jane Matthews-Clark, director of communications at the department.

But the true strength is not being recognised, said Jennifer MacDonald. She cited it as the second-largest resource-based revenue generator in the province. And with the right policies, it could grow to number one.

“When we look at how we’re going to help the New Brunswick economy,” she said, “I’m not saying agriculture is the only answer. But agriculture is one of the strongest investments that we can make to help the economy grow.

“We have an ageing population here and we need to revitalise the economy and provide jobs to stay.

“With a revitalisation of the agriculture industry, that would be a good investment to grow the economy and help all other sectors. Currently, with $1.3billion in value added, it wouldn’t take much to increase that to $3 or $4 [billion], just with the products we already grow. Textiles could be a significant part, whether it’s direct through wool or weaving or even growing hemp or through biproducts. And there’s a lot of value added from our history and there’s lots of new ways to do it too.”

The agriculture options wouldn’t be starting from scratch. Hemp would suit the climate, and flax could be grown – the fields of blue could return.

One of the problems with flax is that most grown in Canada is for linseed oil and for industrial uses, from paints and varnish to linoleum.

William Hill, president of the Flax Council of Canada,14 said flax growing declined when the crop couldn’t compete with returns from other options. He said there was now a resurgence from the health benefits of omega-3 in flax seed, to fibre in composite textiles.

“It’s just the cost per acre relative to return per acre,” he said by phone from Winnipeg, Manitoba. “And flax has difficulty at times competing with other crops as it is, and then to go to something that involves more management and I think the same situation is happening with Europe as the subsidies are reduced for growing alternate crops.

“New Brunswick and southern Ontario and parts of Quebec have a lot of alternatives, everything from corn, soy beans through all the grains in western Canada, the oil seeds, and then horticulture crops and other things that tend to return a little better. But there’s nothing agronomically that says flax couldn’t grow.”

He added: “It’s positioned in kind of a neat space in today’s environment and certainly, if the agronomics can get there and the return per acre can get there and you can build an industry around that, it’s a pretty good story to tell.”

Alvin Ulrich, president of Biolin Research Inc. in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, is one of those leading efforts to find a textile use for the remnants of flax production for industry.15 The stalks in that process currently go to waste, when their linen variety equivalents would be used for making textiles.

His business associate Eric Laugier had done trials in Maine and Quebec in the 1990s to produce “long line” flax for pure linen, halted only by a market collapse in Hong Kong.

Mr Ulrich explained: “I realised that fibre from oilseed flax was not genetically inferior in quality from European fibre varieties. It actually was inferior and/or totally not suitable for many uses, including textiles, because of the crappy way the straw was treated.

“This, in turn, meant that we had the potential to use the fibre from oilseed flax straw for many end uses, including textiles. I was so intrigued and fascinated by this possibility that I wanted to keep working with flax straw.”

The 1990s trials in Maine were near Presque Isle on former potato lands, an extension of the St John River valley, said Mr Ulrich, and European flax experts were impressed by the good yields and fibre quality.

But, he said: “One of the big constraints to developing fibre industries in New Brunswick or other parts of Canada is reaching the threshold of commercial viability. Given the wages people expect in Canada, even in rural areas, means that labour has to be relatively productive both in the growing and in the processing of flax straw and fibre.

“Large potential users of flax fibre generally need a consistent supply of fibre every month at prices that are relatively competitive with other fibres they might use (e.g. cotton, polyester, nylon, jute, kenaf, imported flax fibre). This can be very challenging since an emerging farm product like flax fibre is just that – emerging. Volumes may not be big; qualities may vary greatly; early profits may not be forthcoming.

“Deep pocket investors and/or government subsidies can be very helpful and may be absolutely necessary in overcoming these challenges in the first few years.

“There is a small market for artisan fibres and fabrics made by hand or with simple machines. This is one way to gain experience in growing, harvesting, retting and processing flax fibre. However, it would often be a labour of love because of the small scale of operation. Still, it can give tremendous satisfaction to those involved and set the stage for future commercial expansion. I know this from experience.”

Wool production has continued in New Brunswick even as flax for linen disappeared a century ago. The Campaign for Wool, a project launched by Prince Charles to promote the benefits of the fibre, launched in 2010 in the UK and is now expanding into Canada, seen most recently in his May 2014 visit to Nova Scotia.16

Matthew Rowe, with the Prince’s Charities Canada arm, admitted that the amount of Canadian wool on the market is a “niche within a niche” but they hoped to replicate increased UK sales.

He said: “Wool is all natural and has properties that you look for in other fibres. The Prince saw a generational gap and wool has come to be seen as something your grandmother knits. Orders for wool are going up. We want to demonstrate to farmers that we are able to improve business.”

Mr Rowe insisted that wool was an animal friendly fibre, though PETA campaigns against sheep sheering17 and New Brunswick’s own animal protection legislation has come under fire in the past decade for being inadequate.

But one of the biggest challenges New Brunswick wool faces on the market is that the climate doesn’t suit merino sheep, and the public are convinced that’s the only wool worth talking about.

In fact, Cathy Gallivan, a sheep breeder in the province and publisher of Sheep Canada Magazine, said the up-to-40 breeds registered with the Canadian Sheep Breeders Association could flourish in the area, and there are 33 purebred sheep breeders already.18

Most of the varieties are Suffolk, Dorset, Rideau Arcott, Canadian Arcott, North Country Cheviot, Polypay, Shetland or crosses of some of these, she explained. While her focus is mainly selling the animals for lamb, she does do some value-added processing of the fleece from her Shetland sheep.

“I don’t know anyone in NB who makes their entire income from raising sheep,” she added. “Which isn’t to say it isn’t possible, but it would require a lot of animals. A lot of people who attempt to go that big find they have to hire help, and then they need even more sheep to pay for the help.”

Rachel MacGillivray at NBCCD said the naysayers against New Brunswick wool are a powerful voice, with both weavers and sections of the sheep industry agreeing that they don’t have any good animals and need to concentrate on something else.

“I don’t know how this mindset got here, this idea of, ‘Well what we have isn’t good enough’,” she lamented. “But we do have really great animals here. Why aren’t we investing in what we have, rather than trying to remake our economy or our environment to match somebody else’s?”

She explained that Shetland sheep can produce a very fine fleece, used for traditional Scottish wedding shawls, while Icelandic sheep can produce a soft undercoat and a long guard hair coat, and a foundation for part of Iceland’s economy. Cotswold is another option for the province, she said.

So while Maritime yarn might not be destined to become underwear, there are many other products suitable for wool, and a Canadian climate that makes wool an ideal choice.

“All this money goes into new man-made fibres and stuff and I’ve tried every single one of them and, honest to God, none of them are as good as wool,” she said.

“Rather than trying to force crops or animals, which might not necessarily do that well, into our environment, or trying to change our environment to match them, it’s about figuring out what naturally works really well here, and there’s a lot that does, and what are their properties and how can we market that.”

Does New Brunswick just need a really good PR campaign? Will consumers ever break away from fast fashion? And is there any optimism?

Part 5 – Is New Brunswick ready to wear a different garment?

- Betty Brown at the NFU. ↩

- Canadian government page promoting the Marketing Freedom for Grain Farmers Act. ↩

- Agriculture Alliance of NB. ↩

- NB rural/urban population since 1851. ↩

- Latest employment stats here. Image of August 2014 figures here. ↩

- Sussex Regional High School and agriscience curriculum. ↩

- Figures quoted by NB department of agriculture from StatsCan, divided by 15 counties. ↩

- Finn Report. ↩

- Chaleur RSC. ↩

- Farm Land Identification Program. ↩

- St Mary’s First Nation. ↩

- Tsilhqot’in Nation v British Columbia, 2014 SCC 44. ↩

- Dept of Agriculture “buy local initiative“. ↩

- Flax Council of Canada. ↩

- Biolin Research Inc. ↩

- Campaign for Wool. ↩

- PETA’s anti-wool campaign. ↩

- List of all purebred sheep breeders in NB. ↩