Is New Brunswick ready to wear a different garment?

What are we wearing, by Jason Skinner, artist in residence. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Straining to see through the tightly woven threads of New Brunswick cloth at the state of the province highlights the disconnections and lost opportunities, but so too the potential.

Every part of Tomorrow’s investigation is contained in the cheap sweater your aunt buys you for Christmas, the sofa you sit on to watch TV, the curtains in your bathroom, the long underwear you get in preparation for winter. The buyer holds the threads to weave a new provincial future.

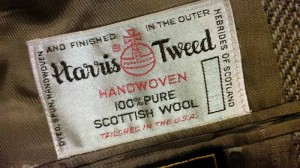

New Brunswick has 71,450km2 of land, just 7 per cent less than Scotland. And yet Scotland is home to Harris Tweed, an industry worth millions to the economy of the Outer Hebrides islands that must, by law, play home to production of the historical cloth. It is a fixture in film and TV, from former Doctor Who actor Matt Smith, to Ben Affleck’s character in the Oscar-winning Argo.

According to the Harris Tweed Authority, 140 weavers work in three mills, producing an average of 58m of fabric in 13 hours. In 2013, they produced 1.2 million metres of Harris Tweed. The Harris Tweed stamp is registered and protected in 48 countries, adding a weight to the brand that is valued by top designers in the UK and around the globe. It is a quality assurance stamp that not only creates a recognisable name from a specific place on the planet, but also a value beyond simple generic cloth.1

That heritage of weaving contributed two centuries ago to the traditions in New Brunswick homesteads, as reported in Part 2. But that past and its potential value today has been largely forgotten.

Alyson Brown, of Legacy Lane, said the industry in the province needed to grow, but there also needed to be more coordination, likely across the whole of the Maritimes and not just New Brunswick, and focused on all fibre, much like the Harris Tweed Authority. A previous association in New Brunswick collapsed when there weren’t the individuals committed to keeping it going, or the money.

“We definitely need more of a presence and a working together,” she said. “That’s one thing I think our country lacks.

“More easterly, there doesn’t seem to be a leader in the industry as far as education and the grading system goes.”

Marketing sells

“You can convince people of just about anything with the right marketing,” said Ms Brown. “Words are key into tricking people into wanting it. It’s finding the right people and getting it out there.”

Applying a New Brunswick-branded quality on raw materials and products could be key, and Harris Tweed and merino wool are both global examples of the power of marketing.

Professor Christopher Moore is the director of the British School of Fashion and the chair in marketing and retailing in the Glasgow School for Business and Society at Glasgow Caledonian University.2

He said Harris Tweed and merino wool, predominantly both have the advantage of heritage that has been maintained through top manufacturing, expert development and retaining a “focused and pure view of what they can offer within the market”.

“Perhaps, within an international context,” he explained by email, “both have also benefited from the impact and halo effect of the very best design houses using them as integral elements of their product collections.

“For example, Chanel herself was a huge supporter of Scottish tweeds and as such, that support put tweed in the centre mind of the international design community. The impact of this form of endorsement is critical. Without excellent product design – the value of these materials is nil.”

Marketing and brand power need each other to work, said Prof Moore.

“A product design is enhanced and supported by the strength of an outstanding raw material ingredient. These ingredients provide the quality credentials of the product and support any claim for distinction, luxury and superiority. Likewise, when a respected designer or brand utilises a specific ingredient – such as tweed – in their product/ranges, then the impact is positive and enhancing. It raises the status of the product. It serves to differentiate and support the positioning of these materials as brands in a powerful and credible manner.

“Textile marketing is more complex. This is because the textile/material is usually not the end product. It is an ingredient of something else.

“As such, marketing for textiles tends to be more orientated towards other businesses, such as design houses and brands, rather than customers. These materials ‘‘come to ’life’ when they are applied and used within these products. So, in many respects, textiles – as ingredients – require an outstanding product in order to secure market recognition, interest and success.”

“Place” is critical, said Prof Moore. The country of origin can represent a distinct heritage, expertise and quality. And, through storytelling, it can give a sense of authenticity and credibility.

“It is a short-hand for a set of values, images, associations and perspectives that represent a particular way of being and living from a geographic area,” he continued. “Location provides a context and anchor to the brand. And in situations where there may be little to differentiate a brand, location can be a very powerful means of achieving some form of distinctiveness.”

So how can producers make the connection with consumers? One of the challenges in a digital era is that only 41 per cent of New Brunswick farms have access to high-speed internet.3 Prof Moore said the key is to somehow create a credible brand.

“We ensure that our students see that a brand is much more than a logo or a symbol. Instead, it represents an exchange of values – either emotional or functional – and these values are based upon what the customer is interested in and what the company can deliver.”

But some brands push the aspirational need to be “in style”, with an ever shrinking world feeding the concept of fast fashion.

Dr Jason Choi is an associate professor at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University where he teaches fashion business subjects such as supply chain management and information systems management.4 He said customers are increasingly demanding more products, broader choices with trendy designs, and shorter delivery time.

“More and more fashion retailers find that they cannot rely solely on pushing sales of existing brands up every year to sustain profit growth,” he said by email. “As a result, they have developed extended brands and product lines.

“Proper supply chain management definitely helps support the brands and enhance the brand values. For example, the fast fashion brand Zara can achieve in Europe the whole lead time from product design to ready-to-sell merchandise in sales floor [of] only about 15 days.

“Fast fashion companies operate with a few elements of their products which are the major attractions: very trendy and fashionable items, relatively simple design, and low price. Since the fashion content is very timely and the price is reasonable – and is in fact cheap when compared to the noble brands – fast fashion companies can capture good market demand.”

He added: “Fast fashion also encourages impulse purchasing in consumers because an item being available in the store now may be gone tomorrow. So, if a customer finds an interesting item, s/he should buy it at once.”

Illustration by Artist in Residence Jason Skinner. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

The choice is yours?

Consumers buy products and services for a range of reasons, said Yasanthi Perera, an assistant professor of commerce at Brock University.5

“It is important to provide a product/service offering that consumers will value on multiple fronts with social value creation being one of these fronts, to ensure that there is a market for what one is trying to do, and to educate consumers on the social issues the business is addressing,” she said.

But, as with fast fashion, it is up to individuals how they spend their money and how they view their purchases, as either helping the community or being trendy, or both potentially.

Denyse Milliken, from St James Church Textile Museum, admitted there is a problem with many in the province who are used to a “cheap mentality”, that everything must be got on the sly or be buying in to the “bargains” offered by firms that sell low quality goods for little.

“I think people are having a hard time,” she admitted, “so therefore, ’they’re going to try and get as much as they can for as little money as possible because they still have this mentality that they need all these things.

“I have a hard time talking to my mother about it even because ’she’s like, ‘Well I can’t afford to buy this, I can’t afford to buy that’. And I’m like, ‘Well mum, if more people did, if more people would put the money in one sweater, locally made, instead of 10 sweaters from Walmart. . .’ ”

Historian and weaver Dr Judith Rygiel said it was as much down to the passion of the producers and then getting that across to potential customers.

“I’m a very passionate weaver – one of my friends says ‘You’re a passionate Acadian’ – I have a passion for fabric and I’m willing to take a lesser lifestyle because of it,” she said. “If you don’t have the passion, if you’re just doing it for the cash, you’re going to be out of business within five years. I’ve been at it for more than 35 years, selling my work, and still engaged, still passionate.

“I’m 66 years old already and here I am making my 500 yards of fabric [a year].”

Another passionate producer and instructor is Denise Richard, teaching visual arts and fibre arts at NBCCD, as well as being a fibre producer in her own right, having exhibited within Canada and beyond.6

Another passionate producer and instructor is Denise Richard, teaching visual arts and fibre arts at NBCCD, as well as being a fibre producer in her own right, having exhibited within Canada and beyond.6

She said when the public visits the college, many have no idea what textiles are.

“Everything in your life is almost textile based,” she said. “Your bed, the rugs on the floor, wallpaper on the wall, the cloths in your kitchen, the bathroom – it’s everywhere.

“Then they start to understand. And then when they see the handmade process, they start to fall in love with what they’re looking at, and then they have a deeper understanding of what they’re getting. Anytime I can get my students to do demos when they’re trying to sell stuff, we sell 10 times the amount.

“It’s educating the public and the consumer about what they’re getting. And quite often I tell my students, you’ve got to sell not only the product but you’re also marketing yourself as a designer-maker. People want to buy from the person – they’re getting a little bit of your personality.”

Ms Richard instructs detailed calculations on how much time it takes to create pieces and the cost of materials, as well as what the market can bear. There would be little point making dishtowels to compete against $2 ones from the “local five and dime”.

“Is that the best product? Is that where you’re going to spend your time, making dishcloths when you can buy them at a five and dime?” she explained about the teaching process. “You have to come up with a different product and you have to price according to not only perceived value but also you consider your overhead and your time and materials.”

As well as prototyping and working to create items for price points of under $10, $20, $50, $100, and $200, they also look at the trends for different seasons. Where at Christmas someone might look for many smaller items to gift to others, in the spring they might look for something more expensive for themselves.

Sell themselves, offer choices and offer quality – the image could be the same as fast fashion, except it’s local.

The finished garment

“We have a passion for farming and for agriculture, a passion for textiles and the fibre arts, for craft in general, for handmade in general, for working with something, being involved in a sustainable practice and the encouragement of natural fibres and not the growth of the petroleum and the synthetics,” said Alyson Brown.

“All of that is why we started it and why we stick with it. We’re our own boss and we get to decide how things go and how it happens and there are a lot of great people in the industry and some have a similar mindset.”

Throughout Tomorrow’s investigation, even after the most blunt assessment of the current state of the province and its agriculture and textiles, its artistry and industriousness, if you ask about optimism, you get passion in response.

“The potential is there,” said Denyse Milliken, “because we have the land, because we need to employ our people, because we need to bring our prosperity back in a different way. We’ve over-forested. I don’t think refurbishing Point Lepreau and bringing in oil from Alberta is going to help our province. I don’t believe fracking is going to help our province. But I believe we’ve got all this beautiful rich farm land here that could be put to good use.

“It is only a matter of time and then we will have people working in textiles again.”

Rachel MacGillivray at NBCCD said friends live in New Brunswick while their husbands work in Alberta and fly home every few weeks.

“And that’s become their norm,” she said. “I think there’s a need for industry here, but I don’t think we want it to be the kind of industry that’s oil fields or the way fashion factories operate in China now. I think it’s got to be more community-based, people-minded, as opposed to companies coming in and dictating -community-built industry. And maybe I am really idealistic, but I think it’s really possible.

“One of the issues is we also tend to have in this society is this overall ideal where you can be happy or successful if you’re making a tonne of money.

“I believe really strongly that we can have a textile economy in New Brunswick and it’s maybe what we need.”

Denise Richard insisted real passion for working 18 hours in a day on a project that doesn’t feel like work is what she tries to instil in the next generation. And all of her students could make a living in textiles, she’s convinced.

She said there was an insecurity that convinced residents, “Oh, I have to leave to compete” and Ms Richard didn’t want to be in that world. Why doesn’t New Brunswick make their theatre textiles the standard instead of Broadway, she asked.

“It’s a matter of staying here and having the confidence and doing the work,” she said. “It’s that question, ‘Can I make it as a textile artist?’ Yes, you absolutely can. But you must do it. You can’t wait for it to happen. You have to research, and get involved, and participate in competitions and get your name out there and do all the social media stuff. That’s a given. You have to be very proactive. I believe very strongly that you can make a living.”

Anna Mathis is ambitious and optimistic.7 Her future depends on whether she can successfully convince you, reading this investigation, to buy her goods, no matter where in the world it is being read.

At 20 years old, she was the youngest of all the interviewees for this investigation – any potential for the province rests on her and others staying in New Brunswick. Newly married in August to a “very supportive engineer”, the Fredericton resident took first place in the Virginia Jackson Design Competition, put on by the International Textile Market Association.8 Fellow NBCCD student Emily McCumber got an honourable mention, and the college was the only Canadian school last year to enter the race, with a student taking first place.

And the first thing Ms Mathis learned was of the other schools she talked to at the competition, none had woven any of the fabric they submitted.

“They had designed it and sent it to technicians to weave it,” she told Tomorrow by phone. “And a lot of their work was done on computers, so even the handpainting that we might do on fabric, they had the ability to just print it off in yards and yards. So that was a really big eye opener.

“I had to weave the fabric to be a certain size and make sure that my colours were on trend and that the style was up to date and it was actually one of the most complex patterns that I wove using 12 harnesses, and all manual.”

Ms Mathis got into textiles through her mother, surrounded by knitting and food processing in the house. One day her mother brought her a little loom and went to the local farmer’s market to ask some women for help. At the age of 15, she was hooked.

Now a graduate from NBCCD with a diploma in fine crafts, fibre arts and with an award under her belt, she said textiles are on the rise in New Brunswick. With the buy-local mindset for food in place, it can now influence other areas.

She is starting a business called Ploome, focusing on selling fibre arts supplies and promoting the education of fine craft. If the textile community grows, more people will buy her skills and products.

“As far as the problems that I face, I do definitely agree that it’s easy to say I’m an artist and people do not value what I’m making at its true cost and its true value,” she admitted. “My weaving, for instance, I actually can’t make any profit – I can only make my hourly wage and the material that it costs me.

“I do believe that I will have another job, but I plan for it to be in my field, educating on the importance of textiles and fibre arts. And hopefully that can be in New Brunswick.”

New Brunswick, argued Ms Mathis, can offer quality “taken-care-of” wool and the resulting textiles. With coordination within the sector and education, there can be success.

“I have a real desire for local and small humble craft,” she said. “I didn’t realise that it was so strong in me until I went to the competition.

“It does very much depend on the people, because building a business is all about giving your customers what they want and designing your products around their needs and solving their problems.

“One of the most important things that people need to realise is that we have been making our own yarn every day up until the last 200 years. It has always been part of our culture.

“I think that it’s necessary to keep this as a part of our life, not just to return to it for fun, but to return to it as a reminder of everything that we’ve gotten through.”

“I do want to stay in New Brunswick,” she vowed.

New Brunswickers have to decide if they are staying in the province, whether they will support its possibilities and weave a new future.

And if they ask, “What on EARTH are you wearing?” they could choose to answer, “With something made here”.

What are you wearing? What economy do you want for New Brunswick? What changes do you want to make yourself or your community to make?

Tomorrow’s first investigation is published freely, as is all our content. But journalism is not without cost. The most basic costs for this four-month project, assuming it is worth 10 cents a word, are:

Phone calls: $224.89 (calculated from total GBP cost at Sept 15, 2014 exchange rate)

Cost per word: 18,355 words x $0.10 per word = $1,835.50

Total: $2,060.39

If you would like to support Tomorrow’s future news, features, investigation, Artist in Residence, Athlete in Residence or other projects, please consider a donation. News builds community, and your donations help further that work.

- The 2013 annual report from the Harris Tweed Authority outlines the full history and statistics of the industry, though not the total financial profit to the economy. The authority did not answer that question from Tomorrow, and the information would ultimately be held by the individual firms and weavers. ↩

- Professor Christopher Moore. ↩

- Statistics Canada reported in 2012 that high-speed internet access was available to just 41 per cent of NB farms, compared to the Canadian average of 44.8 per cent. ↩

- Dr Jason Choi. ↩

- Yasanthi Perera was initially at Mount Allison University at the time of her interview with Tomorrow before moving to Brock. ↩

- Denise Richard. ↩

- Anna Mathis and her online business, Ploome. ↩

- Virginia Jackson Design Competition. ↩