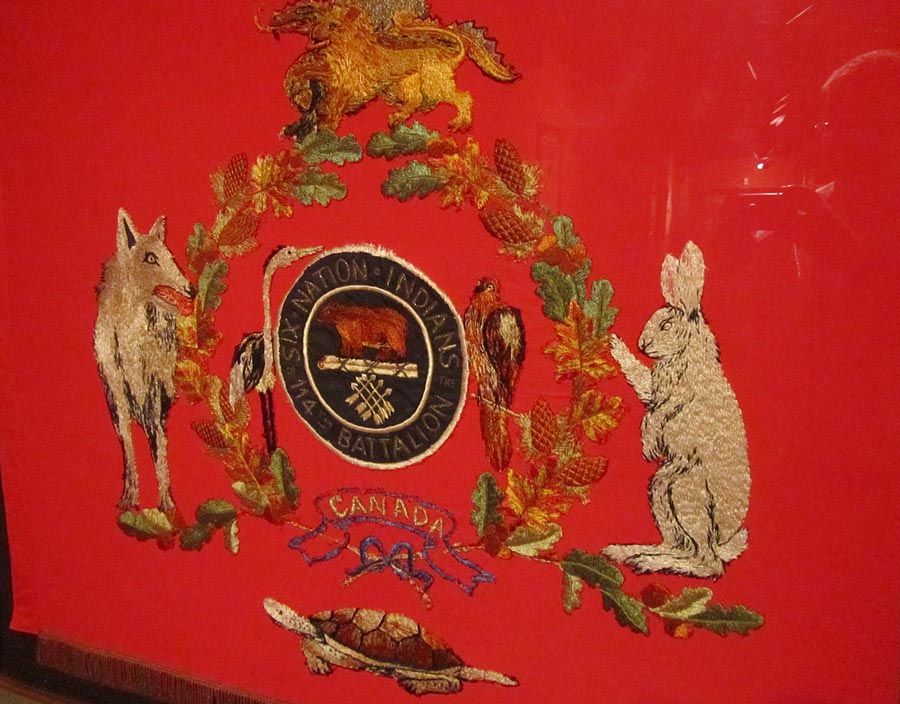

Flag of the 114th Battalion, of the Six Nations, made in 1915 and now kept in the Woodlands Cultural Centre.

A GLOBAL appeal is going out to rediscover the history of one of World War I’s unique regiments.

The 114th Battalion was as colourful in its make-up as were its political intensions and the perception of it by outsiders.

It was broken up for reinforcements to other Canadian battalions once it reached Europe, leaving much of what happened to the individual soldiers unknown today.

Now, Tomorrow is launching an appeal for information relating to the soldiers and also the carved regimental flagpole topper that has been lost for decades.

The group was one of only two made up largely of indigenous men, predominantly from the Six Nations community in southern Ontario1.

Though often portrayed as “Indian” loyalty to the British crown, it was rather loyalty to a centuries-old alliance with Britain, not a servant-master relationship. When veterans returned to Canada however, they were immediately forced to decide if they were “Indian” or “veteran”. As indigenous peoples, they received no veterans’ benefits, particularly the limited treatment at the time for the after-effects of war.

Read more about the 114th in our Yesterday feature

The regimental flag is today held in the Woodland Cultural Centre2, in Brantford, but the pole which carried it has yet to be traced. But like the motivations for joining the 114th, the pole – carved to represent the controversial historical figure Joseph Brant3 – is not a straight-forward piece of war memorabilia.

Close-up of the carved flagpole topper of the 114th, carved in the likeness of Joseph Brant. Courtesy Woodland Cultural Centre.

Tomorrow, working with historians and members of the Six Nations community, approached the Duke of Northumberland estate4, which supposedly commissioned the flagpole. Spokesman David Ferguson said they had no records. He said: “Our archivist has searched press cuttings and Ducal Papers for reference to this flagpole, but has not been able to find anything on it. They have also searched the objects catalogues to see if the pole had ended up here, but cannot find reference to it.”

Similarly, the Imperial War Museum5 had no records of the pole in their collection.

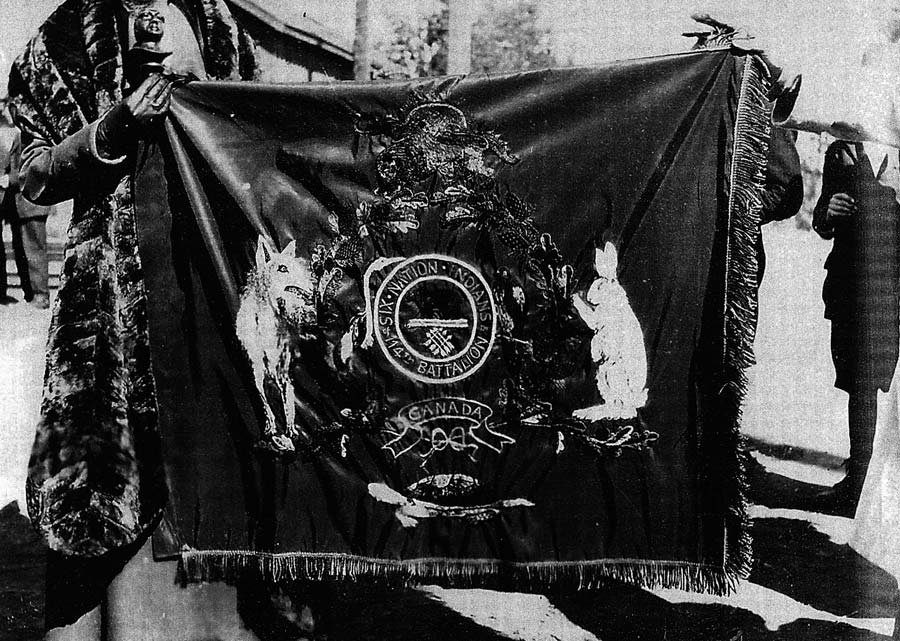

The flag of the 114th Battalion, pictured during World War I with the original flagpole topper. Courtesy Woodland Cultural Centre.

The 114th was formed late in 1915 even as the community’s leadership struggled with maintaining their independence from Canada and desire to help Britain, even though they hadn’t been formally asked to aid the war.

Of the four companies in the battalion, D was almost entirely from the Six Nations and there was also an exclusively Six Nations brass band.

Geoffrey Moyer, vice-president of the Great War Centenary Association of Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations6, said: “Traditionally, the Six Nations has always shown a steadfast loyalty to Britain in times of trouble and the colours presented to the all-native D company of the 114th Battalion truly depict this alliance. Moreover, it records the story of these noble people with the use of its totems.

“Although this flag is proudly displayed at the Woodland Cultural Centre, it is incomplete in that the flagstaff bearing the bust of Joseph Brant went missing overseas. Ultimately the narrative of the Six Nations service during the Great War is unfinished without this key piece missing.

“For any past or present member of the military, they will understand the significance of the regimental colours and that things of this nature do not normally go missing. I believe that because of the sheer beauty and uniqueness of this flagpole, it may have wound up in someone’s personal collection overseas. If this is the case, we would love to see it returned to the Six Nations community in time for the centenary of the First World War next year.”

Paula Whitlow from the Woodland Cultural Centre said that while Joseph Brant remains a controversial figure in Six Nations history, the flagpole topper carved in his likeness was of “exceptional historic value”.

She added: “The notion of a carved Brant flagpole that flew the remarkable 114th is certainly something worth pursuing. The value lies not only in its association with Brant, but representative of Six Nations participation in the Great War. To see something of this magnitude return to Six Nations would be worthy of celebration.”

Researcher Evan Habkirk said interest has been picking up again in the community but that much more work needed to be done by academics and others to make Six Nations and Brantford and Brant County more aware of the local history from World War I.

The Great War Centenary Association is working on memorialising the different communities, complete with education projects for students of all ages, online databases for genealogical research and others.

Brantford claimed the highest enlistment rate of any community in Canada, Six Nations had the highest indigenous enlistment as well as the highest enlistment as proportion of the total local population.

Mr Habkirk said: “We’re still kind of working in a void. The idea is to get the public involved in the memorial process, to let them know what these communities – which were fairly big communities at the time – were doing to help the war effort and, sometimes, not to help it. We had the big conscription crisis and we had a lot of farmers in the area, and that didn’t go over really well in 1917.

“We’re trying to just mobilise the knowledge of these community to understand what it is the first world war might mean to the community and to make them have pride in those ideas.”

There were Six Nations members who rushed to enlist when war broke out in 1914, but hesitation by the Six Nations Council, the oldest form of government in North America7. Because they insisted on a formal request from their original British allies, which never came, they were often at odds with the Canadian government. Even as relations with neighbouring Brantford got stronger, those with the department of Indian Affairs got worse. By 1924, bureaucrats would suppress the traditional government in favour of an elected council.

Mr Habkirk said: “There’s been a lot of press about the negative effects that the Canadian state has had on First Nations peoples, but it has actually woken up the consciousness of some people, non-native people and native people, who want to know more about the history of how we got to this point.”

Mr Habkirk said he would like the search for information about the men of the 114th and the flagpole to fuel a general acknowledgement of their contribution to history.

He added: “We see the traditional people who look at this as a way to further Britain’s recognition of their alliance. We see some who just want to use it as a way to force the Canadian government to deal with the fact that they’re native and they’re participating.

“This story on the 114th shows that an entire community was, in the case of both Brantford and Six Nations and Brant County, weirdly brought together by this unit for totally different reasons. The outside communities thought Six Nations were doing it because they were good British loyal people. But some Six Nations people were doing this as a specific national stance.”

- If you have found information on the flagpole topper or the men of the 114th, contact Tomorrow and we will pass to the researchers.

- http://www.sixnations.ca ↩

- http://www.woodland-centre.on.ca ↩

- Summarised history of Joseph Brant. ↩

- http://www.northumberlandestates.co.uk ↩

- http://www.iwm.org.uk ↩

- Web: doingourbit.ca or Twitter: @GWCAdoingourbit ↩

- About the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. ↩