Why did Canada and Scotland take very different approaches to welcoming Syrian refugees?

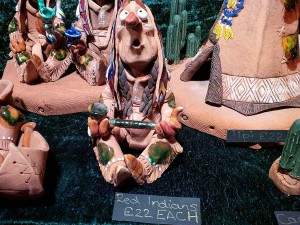

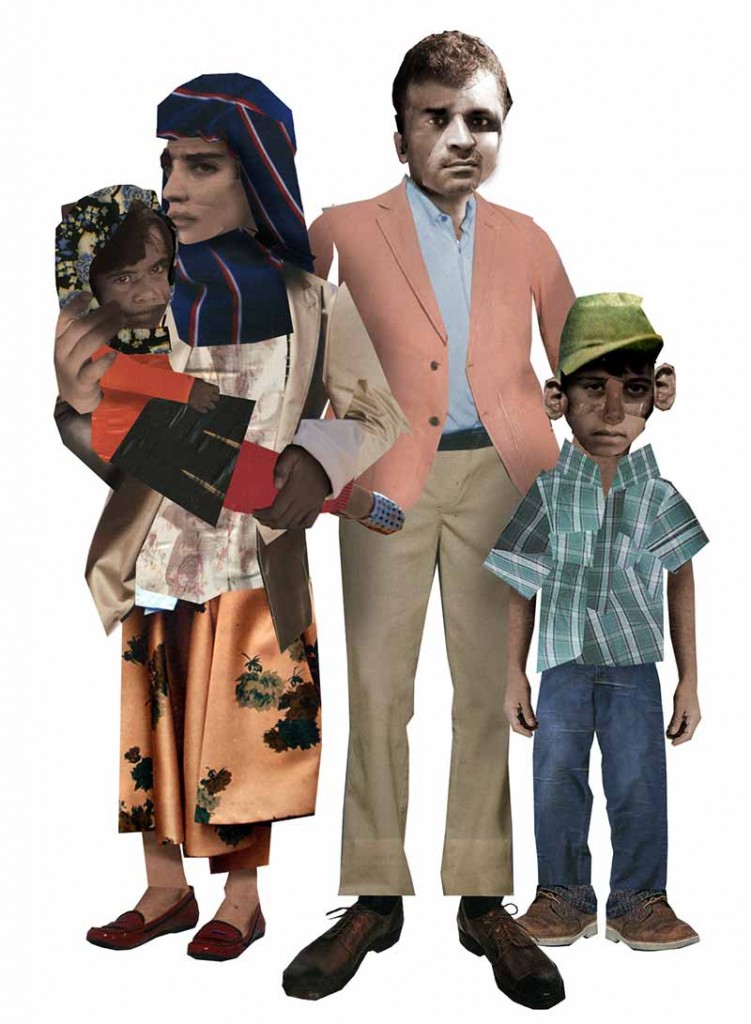

Refugees, by artist in residence Jason Skinner. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence.

Behind refugees arriving to new homes from war-torn Syria in recent weeks there have been radically different government positions and advice, Tomorrow has found.

The contrasting approaches were taken in Canada and Scotland to press access to the arrivals amidst massive public interest.

And while both nations referred to protecting “vulnerable” persons, they also have systems for applying refugee status or deporting individuals that are almost entirely hidden from public and media view.

The Scottish Government denied press access to the first arrivals of Syrian refugees in November as local councils who would be rehoming them urged privacy while they settled in. Refugees who found safety in Scotland a decade ago also advised against media interviews at the airport.

Just weeks later, Canada’s new government welcomed refugees with the prime minister at the airport and pictures and video broadcast around the globe. It played particularly well in the neighbouring United States in the midst of presidential candidate Donald Trump’s inflammatory statements against Muslims.

Press ‘made it difficult’

Humza Yousaf MSP, Scottish Government minister for Europe and international development, said there was “much talk” between their administration, local authorities, and the Home Office at the UK level about the best approach. Refugees themselves advised against press access.

“We have refugees who sit on our task force,” the minister told Tomorrow by phone, “and in amongst our conversations had a discussion with Congolese refugees who arrived here over a decade ago in Scotland. And they mentioned that the press around their arrival made it very difficult for them to settle in and they suggested to us that it would be better to shield the refugees from any kind of press intrusion upon arrival.

“So we took the advice of refugees first and foremost to come to that decision.

“Secondly, there could not have been, I think, a more tense time for refugees to arrive in Scotland and the UK than literally days after the Paris attack on the 13th, first arrival of the 17th of November. There couldn’t have been a more tense time.

“We thought because of all of those factors, the right approach would be for refugees to be protected.

“We always did this with the understanding, of course, and the knowledge, that there’s only so much that you can protect refugees from.

“I understand local newspapers in particular would be able to find out where refugees were and there was nothing stopping them from knocking their doors and we weren’t going to be too prohibitive. We couldn’t be too prohibitive, even if we wanted to be, and understanding that we shouldn’t be either. On the initial arrival we thought it was important to protect their identity.”

Pauline Diamond Salim, media officer at the Scottish Refugee Council, said they had no operational role in the arrival of refugees, but are part of the government’s task force on Syria and agreed with the approach.

“Over the last few months people have been moved by the hardships faced by refugees and in Scotland we have seen a wonderful increase in public goodwill towards people seeking refugee protection. Alongside this goodwill there is also a desire to know more about who refugees are on an individual level.

“It is natural to be interested in others, especially when they are newly arrived in a community and most of us want to get to know our new neighbours or colleagues. However, I think most people would agree that it is only fair to give people the time and space they need to adjust to their new circumstances before giving media interviews.

“It is difficult to strike the right balance between satisfying an understandable public desire to know more about who people are, and making sure that people are not put under any pressure in their early days of arriving in a new country.”

New government, new homes

In Canada, part of the Liberal Party platform before they won the October federal election, and reasserted immediately after, was to take in 25,000 Syrian refugees by the end of 2015, something which has now been stretched into February. The first arrived in Toronto on December 11 with new PM Justin Trudeau welcoming the initial families off the plane.

Images of the prime minister and refugees appear on the front page of the Citizenship and Immigration Canada [CIC] website. The department has now been renamed by the new government as Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

Faith St-John, communications officer with IRCC, told Tomorrow in an email statement that some families were asked before boarding the Canadian military flight if they were interested in speaking to the media when they arrived.

She said: “Several families volunteered to do so, and signed consent forms indicating that they gave their full permission to have their photographs taken. These families deplaned first. Families who were not interested in participating in any public activities, deplaned later.

“Media who expressed interest in the arrival of the first flight were advised by email that for security and privacy reasons, media would not be able to access the tarmacs or the departure/arrival areas of the flights bringing Syrian refugees to Canada. A media pool was granted access to a controlled area of the Toronto airport, under escort.”

Canadian government website promoting the recent Syrian refugee arrival. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence.

She added: “The Canadian government is aware of the hardships that these families have faced, and respected the wishes of any person who did not wish to participate in any public activities. Only those families who volunteered were part of the public activities. As mentioned above, media was not given access to the tarmacs or the departure/arrival areas of the flights bringing Syrian refugees to Canada. For security and privacy reasons, only a small media pool was granted access to a controlled area of the Toronto airport, under escort.”

Tomorrow checked with some high-profile aid organisations in Canada on their involvement in the arrivals. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Canada deferred all questions to the Canadian government. The Canadian Red Cross said they supported the approach.

Kathleen Kahlon, director of communications with the organisation, said they view the presence of the media during a disaster or special events such as the refugee arrival as “normal occurrence”.

She said: “We work with media to help them deliver information that is important for the public to know, while also protecting the privacy of the people we are assisting.

“The Government of Canada made us aware of their plans prior to the arrival of the refugees and we were comfortable with their approach given the care and consideration of privacy that guided those plans.

“Support will be provided by the Red Cross in temporary accommodation sites in both Quebec and Ontario to help integrate Syrian families in their new communities.”

By contrast, Lifeline Syria, a group formed in June 2015, said they were not consulted on the process but that half of those families who have already arrived connected to their sponsors were willing to talk to the media.

Lifeline Syria’s confidentiality policy states there must be informed consent for media requests – including understanding how widely images may appear and be shared – and particular concern shown to personal information that could lead to identification of a family.

It also states: “Refugee families are symbols of hope and strength; families who have been given the opportunity to resettle in safe, welcoming Canadian communities.”

‘Vulnerable’ and hidden

Prime Minister Trudeau, as cited on the CIC/IRCC website, stated there was a responsibility to expand refugee targets and give victims of war a “safe haven”.

“The resettling of vulnerable refugees is a clear demonstration of this,” it adds.

But protecting “vulnerable” refugees or those applying or rejected for the status are largely hidden from the public view in both Scotland and Canada.

Canada’s Refugee Protection Division and Refugee Appeals Division with the quasi-judicial Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) are closed to the public. Whereas the Syrian refugees have been granted status before they arrive in Canada, the RPD and RAD deal with claims made within Canada. Because they are not yet refugees, the law says the hearings are private.

Is justice blind? Illustration by artist in residence Jason Skinner, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

In an email statement, Melissa Anderson, senior communications advisor with the IRB, told Tomorrow: “The legislation under which the IRB is governed has provisions for the hearings of refugee protection claimants, not refugees, to be private. There is no automatic privacy provision for either refugees or failed refugee claimants appearing before the Board’s Immigration and Immigration Appeal Division (with the exception of a failed refugee claimant who has an application for a pre-removal risk assessment with IRCC).”

The administrative tribunal referred Tomorrow to their “chairperson guideline” on “vulnerable persons”, who they define as including: “the mentally ill, minors, the elderly, victims of torture, survivors of genocide and crimes against humanity, women who have suffered gender-related persecution, and individuals who have been victims of persecution based on sexual orientation and gender identity”.

Similarly in Scotland, those who have their refugee claims rejected and await deportation or appeals, or those with criminal convictions, are held in “Dungavel House”, an immigration removal centre in South Lanarkshire frequently referred to as Dungavel Detention Centre. Long a source for significant dispute between the Scottish Government and the UK government, which retains control of immigration and borders, the site has been opposed by campaigners and politicians and only accessed by reporters rarely through subterfuge or smuggled information.

Humza Yousaf said Dungavel wasn’t kept isolated in location and excluding press and even human rights scrutiny to “protect” individuals.

He said: “Anybody who tries to make the argument that the processes in Dungavel are carried out away from the media spotlight is for the protection of asylum seekers, is frankly lying through their back teeth.

“That is not the primary reason why media and cameras won’t be allowed into Dungavel. It is frankly because the practices of detaining families and children is a practice that most normal people would see as unacceptable. I’m very much of that view. So the reason for the lack of any public scrutiny in Dungavel is not for the protection of the asylum seeker – far from it.”

Kate Alexander, director of the Scottish Detainees Visitors, said there has been more interest into immigration detention centres this year than ever before. And voices from inside centres in the UK are getting out to the public through campaign groups and social media, even if the press can’t get in to interview detainees. As well as individuals who have been denied refugee status and may be appealing, there are also many with other non-UK citizenship following prison sentences for criminal convictions.

“This is the most interest I have seen in detention,” she told Tomorrow by phone. “They’re very secretive places, there’s quite a lot of effort being made by organisations like us, Detention Action and Detention Forum to open them up. The government does a lot to try and make them as invisible as possible, but there are strenuous efforts to make them more visible.

“Quite often people want help to be more public. Earlier this year we learned people in Dungavel were undertaking a hunger strike in order to bring attention to indefinite detention. But one of the difficulties is that they’re stuck in there and nobody can see them and they asked for our help in bringing that story out. So sometimes people actively want to shine a light on their position in detention.”

Ms Alexander admitted that the public attention on the subject of migration in 2015 has resulted in more interest in her group by volunteers and what is going on at Dungavel. There has been a “trickle-down effect to Dungavel and places like it”, she said.

The Home Office, who Tomorrow asked about both Dungavel and their approach on press access at arrivals in November, offered a limited statement that didn’t answer the questions posed.

“It is a matter for each individual local authority how they deal with and facilitate media requests once they have resettled refugees,” emailed press spokesman Michael Charouneau. “The Home Office’s priority is to ensure these vulnerable people are able to settle into their new homes and communities and given the opportunity to rebuild their lives.”

What do we need to see?

With millions of people having fled the conflict in Syria and Iraq, as well as other countries around the globe, and with fiery rhetoric against them from some politicians and their supporters, is there a “need” to see new arrivals and immigration more widely?

An Ethical Journalism Network report criticised vast swathes of the media in Europe and elsewhere for missed opportunities and fear mongering about the refugee and migrant crisis in 2015. It found stretched press resources and news organisations being led by politicians and negative depictions of “numbers” versus human stories.

Mr Yousaf said he understood the Canadian approach and was sympathetic to a desire for positive coverage and celebrating the thousands of good acts in support of the new members of communities.

“There should be as much public scrutiny in what we do and how we resettle refugees as possible and I would welcome that,” he told Tomorrow. “All we were simply doing on arrival was to ensure that the advice we’d been given from other refugees was taken on board.

“Both refugee and asylum issues are not universally popular. If anybody thinks that the accepting of refugees was a popular decision then they should just come out knocking doors as I do. It’s not what you’d call in the business a vote winner by any stretch of the imagination.

“The same when it comes to asylum seekers and those that are in Dungavel. There’ll be many people who will say, I’m afraid, ‘Well these people deserve to be locked up because they’ve failed their asylum and they shouldn’t be in the country’.

“And the other camp, which I belong to, which says these people have not committed any criminal offence, even if they have failed an asylum application and they should not be treated like criminals and should not be detained – neither they or their children. So it’s a very polarised debate in the first place, and so nuances often get lost in polarised debates.”

Of the clothes and toys distributions, befriending neighbours and other welcomes going on around Scotland, and covered by the press, Mr Yousaf added it was “very, very heartwarming to see”.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence.

No relevant issues on principles 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 10 or 11.

Principles 5, 6, 7 and 8 intersect on this subject: “a duty to openness” and “comfort the afflicted and afflicted the complacent”. We have already drawn attention in 2015 to the complacency around media and public access to immigration courts and tribunals. Refugees also arrive in countries seeking protection all the time, but rarely make the news unless propelled by other events, such as political scapegoating. But part of the duty to “comfort the afflicted” means both our reporting and our interaction must be aware of a need to provide “safe harbour” to readers and interviewees.

So, politicians inviting the media to speak with or photograph refugees who are, according to their own press statements “vulnerable”, does not mean it is automatically right to do so. And even if they are interviewed and photographed, their personal details and aspects of why they have fled their home country must be treated with care and caution. Just as “justice must be seen to be done”, and this certainly applies to unseen refugee and immigration tribunals and courts, this must be balanced with protections for individuals in some cases, if only as journalist sources. There is no single rule on the subject of human migration.