How Canada’s Jewish community lost, then won, the debate on animal ‘cruelty’

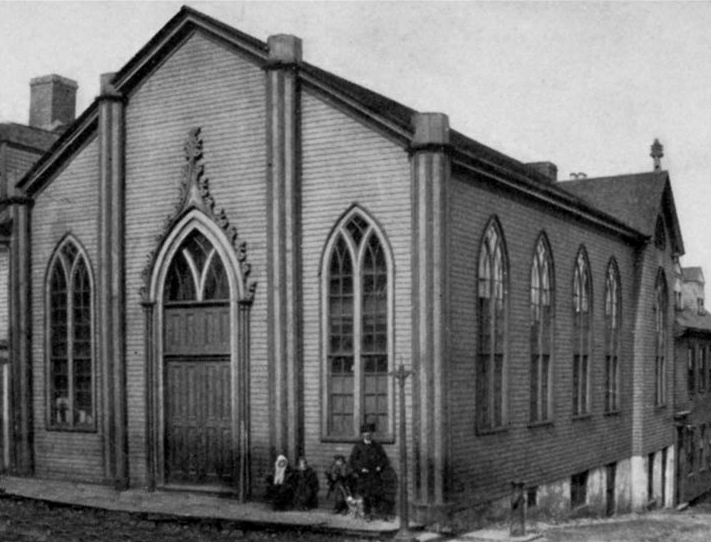

Baron de Hirsch Synagogue, 19 Starr Street, Halifax, ca. 1902, from the book, “Halifax, Nova Scotia and Its Attractions, 1902”. Courtesy of Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax, NS.

It was called “one of the greatest misfortunes which ever befell Canadian Jewry” but is an episode now almost completely forgotten.

One hundred years ago this April, the Jewish community in Halifax, Nova Scotia, had a pillar of their faith upended, branded a “pointless method” and a rabbi fined for being cruel.

The kosher butcher in the city was found guilty of using inhumane practices by cutting the throat of animals to slaughter them.

An appeal just weeks later reversed the sentence and decided the Jewish method was in fact “preferable” to the practice of slaughter by stunning animals first.

The episode brought together a mix of religion, science, local-versus-national politics and endless assumptions about animals from those who killed them.

But why did the trial take place, why in Halifax, and was it an anti-Semitic attack?

The first synagogue in the Maritimes

Jews were amongst the earliest arrivals in 18th-century Halifax, but a historical record of them was largely missing for several decades, only to re-emerge in the 1860s and 1870s.

The families ranged from settled North Americans – both Americans and Canadians – to Eastern European Jews fleeing persecution.

A former Baptist church on the corner of Starr Street and Hurd’s Lane – now roughly under what is now Brunswick Place office centre near Citadel Hill1 – was bought by the Jewish congregation, then naming themselves after Baron Maurice de Hirsch, the once prominent European philanthropist.

The building required repairs and $1,000 was donated by the Christian community, at the request of the Jewish congregation2.

On February 19, 1895, a large crowd turned out for the consecration of the first synagogue in the Maritime provinces. According to Halifax newspaper accounts, the 500-600 person capacity was filled by 1.45pm, 45 minutes before the ceremony was ready to start. “Hundreds” were turned away3.

In the years following the consecration, as the community grew in numbers, the businesses run by Halifax Jews increased in number and diversity, mostly on the eastern side of the Citadel, above the waterfront and docks. Many families started out living above their businesses, moving on to separate homes when they could afford it.

As the Jewish community grew in Halifax and the rest of Canada, so too did the need for services such as that of a kosher butcher, or shochet. The key distinction was, and is, that the Jewish method of slaughtering – or shechita4 – doesn’t allow for the animal to be stunned before the ritual cutting of its throat, compared to what was called in court the “Gentile method”.

Although the Halifax trial in 1913 was unique to Canadian Jewish history, it wasn’t alone globally.

News articles from The Jewish Times (later renamed the Canadian Jewish Times) regularly recounted attacks on shechita in various countries, including Finland, New Zealand, Britain, and Norway, usually involving proposed or enacted laws against the practice5.

By contrast, in Germany in 1911, there was a bill put forward to recognise the Jewish method of slaughter as humane.

Scientific papers written in the years leading up to Halifax trial argued about how to recognise consciousness in an animal and the length of time it took to die – questions that were key to the case and its appeal6.

One pamphlet, published in Massachusetts just months before the trial, insisted the opposition to the Jewish method wasn’t anti-Semitic – the quarrel was just with “their ritual of slaughter. . . I believe they think their method humane, though I am sure but few of them have ever witnessed it”. But the author added that swift reform should be the goal “in a land boasting a Christian civilisation”7.

The trial – a “pointless method”

Just months after that pamphlet was published, on April 1 or 2, 1913, Scottish-born Andrew Williamson from the Halifax Society for the Prevention of Cruelty (SPC) was delegated by the Crown8 to bring charges in the Halifax police court against Rabbi Aba (Abraham) Gershom Levitt, for inhumane practices in kosher slaughter9.

There are no official court records of the original April 1913 trial, with a noticeable gap in police court papers over several years at the time.

However, a transcript of both the trial and appeal exist in the Montreal archives of the Canadian Jewish Congress, as well as details from newspaper coverage, both from Halifax and from Montreal’s Jewish press10.

The case came before Stipendiary Magistrate George H Fielding, with Robert H Murray prosecuting and W J O’Hearn defending.

The trial consisted almost exclusively of evidence brought by the prosecution and the SPC and very little favouring the Jewish method. Mr Williamson was the central witness, as well as veterinary surgeon Dr Philip Gough, followed by slaughterhouse owners in the city and finally Rabbi Levitt.

According to the trial, Rabbi Levitt conducted his ritual slaughtering on the premises of the public slaughterhouse of James Shortell, one of the witnesses called against him.

Mr Williamson had been investigating the Jewish method since November 1912 and described what he saw when Dr Philip Gough accompanied him to the March 19 killing of a heifer by the defendant. He recounted in detail how the animal was tied and strung up, then,

. . . the head turned over with muscle and throat up and head resting on horns on floor. Then defendant stepped up and cut the heifer’s throat. The animal struggled, pounded on floor, kicked with the fore leg, and gasped, and put out his tongue, gurgled in the throat, kept it up for five minutes, then passive for a short period and action of the same kind set in again. Fourteen minutes from throat cut till ceasing of action. After cutting throat eyes gradually lost brightness.11

Under cross-examination, Mr Williamson admitted he had only been in Halifax for five months and Canada for three-and-a-half years. The supposed expert “never slaughtered cattle. . . was never employed in slaughterhouses” but had seen “as many as 1,000 cattle killed. . .[and] about 50 killed at a time”.

He then concluded that less struggling is caused by stunning than by the Jewish method. Mr Williamson said: “I infer pain from the action, such [as] kicking, after the throat [is] cut. I have seen defendant’s method twice or thrice practised. It, to my estimation, produces pain.”

Insisting that he knew what he was talking about, all [the] while undermining his credibility, he concluded: “I am not an expert. I infer from the physical effort. I laid the complaint. Cutting the throat causing pain.”

Veterinary surgeon Philip Gough based his knowledge, like Mr Williamson’s, on experience and the “looks of the animal. From practice I am able to say if from appearance [the animal] is conscious or not”. Both the first two witnesses agreed that “pain” continued in the animal for 12-15 minutes after its neck was cut.

The following Tuesday, the trial resumed to a chorus of Halifax slaughterhouse proprietors. Sidney R Tucker, James Shortell, and James F Peeley all used stunning to render “instantaneous” unconsciousness. Mr Tucker told what method he used. Mr Shortell said the defendant would not allow stunning. Mr Peeley said only that, “as to methods [the] Jewish is longer and most painful”.

Rabbi Levitt was then sworn in. He explained what the Jewish method requires, as dictated by law. He told the court that he couldn’t say how long this animal took to die, but that typically the time until death was between two and five minutes.

Rabbi Levitt went through various qualifications and reasons for the Jewish method, but didn’t infer pain based on the animal’s struggles.

Dr Gough was recalled to the stand and his evidence linked death with pain so that time of struggle and pain became identical and indistinguishable.

Defence lawyer Mr O’Hearn raised the point that the law allowed a certain degree of pain in the killing of animals, and that this degree was not exceeded by Rabbi Levitt. But his argument on religious grounds was dismissed by Magistrate Fielding as “no answer to the law”.

After all the evidence, Magistrate Fielding concluded on April 23:

“I look at it this way. . . I quite understand the view that persons must be cruel in a relative way to kill animals for food, and must take life to get food. If there are two methods by which that can be accomplished and one is more humane than the other, I think the more humane method should be followed. If the least humane method is followed it is unnecessary cruelty. It has been suggested that to convict would deprive a certain portion of the community of food. That may be.

“I don’t see that it is necessary to slaughter animals in this fashion because pain and suffering is caused which is unnecessary. I cannot see why there should not be a conviction. I have nothing to do but administer the law. To my mind this is a very painful way of killing animals. This method has been practised for over 3,000 years without obstruction, and while perhaps it seems a cruel thing to continue in this way all these many years, still at the same time these people have conscientious scruples, and this is the first time the method has been attacked. It is really setting a principle.”12

Magistrate Fielding said a “former rabbi” in the city would cut the animal’s throat and then stun it, but Rabbi Levitt would not allow stunning.

Rabbi Levitt was fined $6 and $7.65 in costs for causing “unnecessary pain and suffering while slaughtering”.

From the moment the rest of the Canadian Jewish community found out about the case they were alarmed. And Halifax turned to their only hope, in Montreal, then home to the country’s largest population of Jews.

The case was the talk in synagogues across the country and the Canadian Jewish Times said “a great injustice had been done to the Halifax community, which could result in endangering the position of Jews in the Dominion”. The paper, on its front page of May 2, 1913, declared it an attack on “Jewish ritual law”.

Meanwhile, the SPC started a campaign in Nova Scotia to ensure all animals, large or small, were stunned before killing, according to the Halifax Herald. The prosecutor was quoted as saying the city was “fortunate in having a fearless magistrate”, where other cities might not challenge the Jewish method.

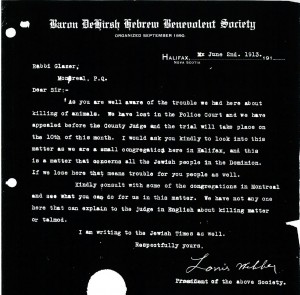

Letter from Louis Webber to Rabbi Glazer asking for assistance in the appeal of the court decision against Rabbi Levitt, June 2, 1913. Courtesy Canadian Jewish Congress National Archives.

Halifax’s Jewish community wrote to Montreal just a week before the appeal in June and pleaded for help from Rabbi Simon Glazer, then Chief Rabbi of the United Synagogue of Montreal and Quebec13.

Louis Webber, president of the Baron de Hirsch Hebrew Benevolent Society14, wrote: “We are a small congregation here in Halifax, and this is a matter that concerns all the Jewish people in the Dominion. If we lose here that means trouble for you people as well.

“We have not any one here that can explain to the judge in English about killing matter or talmod [sic].”

The letter was also sent to the Canadian Jewish Times, which was home to sniping between the paper feigning ignorance and lack of contact with Halifax after the trial, against readers claiming a the lack of “action”.

One slammed the paper for failing to help the “small and poor community” of Halifax in the face of “one of the greatest misfortunes which ever befell Canadian Jewry”15.

The appeal – the “preferable” method

Even if it wasn’t overtly stated as an anti-semitic attack, challenging and even criminalising such a foundational part of the Jewish faith was going to be considered an attack on the community itself. Though there is little evidence of Halifax’s own opinion of the case, the wider Canadian Jewry certainly took it as an attack on the faith.

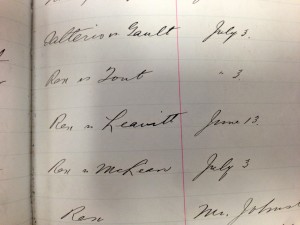

District Number One (Halifax County) procedure books, listing of King v “Leavitt” appeal, June 13, 1913, Nova Scotia Archives. Photo taken by Kurt Sampson.

On June 13, 1913, an appeal went before Judge William Bernard Wallace of the County Court, complete with new witnesses and wider perspectives.

Mr Williamson again opened with essentially the same testimony. Again, he ate away at his own testimony: “The head was pretty well severed. . . I would deny a statement that the struggling was any evidence of pain. I have not studied any science. . . I don’t regard myself as an expert in this matter. I think that struggling means pain.”

Dr Gough stated death by stunning occurred in one-fifth the time of the Jewish method. Mr O’Hearn, again for the defence, nibbled at Dr Gough’s credentials and experience. Dr Gough admitted: “We are all liable to make a mistake. It may be possible that my opinion is wrong.”

Dr Gough’s scientific analysis was that “consciousness has relation to [brain] control. . . the brain is in the head. I think that that floundering head had consciousness for three or four minutes. . . After the cutting of the throat I would say that there was still blood in the brain”.

As Dr Gough was re-examined by the prosecution, the time limits for conscious pain became shorter and shorter. The blink of the eye is examined to determine consciousness. He said: “I would consider that a hen with it’s [sic] head cut off still suffers pain.”16. “The animal must be conscious to suffer pain. Consciousness is necessary to pain. I believe it would be conscious with it’s [sic] head off for a short while.”

Howard McFatridge was sworn in as a veterinary and a graduate of the same school17 as Dr Gough. However, Dr McFatridge entered an entirely new “scientific fact” to the trial: “After the animal’s throat is cut in that way, the animal is unconscious of pain. The struggling pounding and kicking is a reflex action.”

Dr McFatridge stated upon cross-examination that he went by “the pulsation to determine consciousness” compared to looking into the eyes. He declared that the Jewish method was “as good as any”.

Rabbi Simon Glazer came to defend Halifax, but managed to do it with a dig as well. He defended Rabbi Levitt’s strong credentials and his capability of “performing the operation well”, but added that: “The paraphernalia of the slaughterhouses in this city is not modern.”

Rabbi Glazer refuted any connection of reflex action to consciousness: “A motor may be shut off by an engineer, but the momentum may continue.”

Dr David Fraser Harris – who was quoted in the Halifax press after the trial defending the Jewish method18 – held the chair of physiology at Dalhousie University, having a doctorate of medicine from the University of Glasgow and a doctorate of science from the University of Birmingham.

He told the court: “A rooster with it’s [sic] head off could have no consciousness. … Consciousness has it’s [sic] seat in the brain alone. There is no pain where there is no consciousness. The quickest way to stop consciousness is by cutting the throat. The convulsions spoken of have nothing to do with pain.”

Judge Wallace was quoted as saying that he had “no hesitation in coming to an immediate decision”. He found Rabbi Levitt “not guilty'”.

It was reported: “In his opinion, based on the evidence before him, the Jewish method was more humane and therefore preferable to the other method. The appeal of the defendant from the conviction was allowed, and the prosecution was dismissed.”19[Tweet “”The Jewish method was more humane and therefore preferable to the other method.””]

For all the significance and concern over the case at the time, within weeks it had all but vanished from the public’s attention.

Almost no record exists of the relations at the time between the Jewish communities of Halifax and Montreal, other than the plea for help from Louis Webber. A later article in the Canadian Jewish Times in 1914 revealed that the Montreal community judged Halifax’s synagogue to be “hardly an inviting place of worship. This is probably the reason why the Halifax Jews keep away from it”20.

A reader – in Sydney, Nova Scotia, not Halifax – hit back, apologising that “only a few of our present congregation can afford to support silk hats on their craniums”21.

Three years later, the congregation’s home was gone. Twenty-two years after the first synagogue in the Maritimes was consecrated, the building was damaged beyond repair in the “Halifax Explosion” of December 6, 1917. The blast, caused by the collision of the Belgian relief ship SS Imo with French munitions ship SS Mont-Blanc, was the largest man-made explosion before the atomic bombs of the second world war, leaving more than 2000 people dead and 9000 wounded22.

Although no Jews were killed in the explosion, much of the early community’s history was lost with the building. The Torah scrolls were saved, however, and later became part of a new synagogue founded in 1921.

Of what remains of the historical records of the Jewish community, the trial of the shechita remains the most detailed and dramatic chapter of that first community’s history.

Note: This feature is based on research conducted in 1999-2000 by reporter/directing editor Tristan Stewart-Robertson for his BA honours history degree thesis at Dalhousie University.

- The formal address was 19 Starr Street, and the building known as both the Starr Street Synagogue and the Baron de Hirsch Synagogue in historical records. Currently, Halifax Developments. ↩

- There is no formal record of exactly where the money came from, merely the citation of a contribution. ↩

- The Morning Chronicle, February 21, 1895, Vol XXXIII, No 44, 2. ↩

- The trial is frequently referred under the title of the process, “shechita”, not the individual, shochet. There are variations of spelling in some records. ↩

- The Jewish Times and Canadian Jewish Times articles used in researching the original history thesis were courtesy the National Archives of Canada. Scans of some of those pages are included with this feature under fair use for news reporting. Copyright remains with the archives. ↩

- J. A. Dembo, The Jewish Method of Slaughter, translated from the German with author amendments (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Turner & Co, Ltd., 1894). ↩

- Francis H Rowley, Slaughter-House Reform: in the United States and the Opposing Forces, “A pamphlet prepared especially for the humane societies of the United States” (Boston: The Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, 1912 – the date does not appear on the document, although it does on the archival listing, and the content indicates publication after August 1912). ↩

- The title of the group was the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty, and did not distinguish the “to animals” until after the trial. Under the appeal, it details that the SPC was delegated by the prosecution to investigate. The Jewish Times refers to the “1 or 2 April” for the summons to Rabbi Levitt, and the paper received a trial clipping from Halifax on April 9. ↩

- Rabbi Levitt is noted as the rabbi of the Webber Shul, a breakaway private synagogue on Proctor Street in 1912, according to research by historian Sara Yablon. None of the coverage of the trial or appeal distinguishes Rabbi Levitt as part of a separate congregation, nor the possible relation of Louis Webber, who later writes to Montreal appealing for help. The congregations reunited in the 1930s. The full name of Rabbi Levitt comes from Simcha 100: 1890-1990 100th Anniversary Book. Halifax: Baron de Hirsch Congregation, 1990. ↩

- There are no details where the transcript came from. Various reproductions from the trial and the appeal exist, but without any clear reference to if the origin was a formal court transcription, or a reproduction of local newspaper coverage. ↩

- Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) National Archives Collection, Series ZD (Communities)/Halifax/File#1 1913 (?) “The King vs Levitt” (evidence). ↩

- National Library/Canadian Jewish Times, May 2nd, 1913. Vol XVI No 21, p8. ↩

- Rabbi Glazer: http://imjm.ca/location/1178 ↩

- The society was the official body of the synagogue. See scan. From the CJC archives, Personalia Files, “Glazer, S-Various File”, June 2, 1913. ↩

- National Library/Canadian Jewish Times, June 13th, 1913. Vol XVI No 27, p12-14. ↩

- The CJC has various copies of a transcript of the appeal, without stating its origin. All the quotes here are from those transcripts. Kurt Sampson assisted recently to double check Nova Scotia Archives records, which only includes just the misspelt name of “Leavitt” for June 13 [District Number One (Halifax County) ↩

- Ontario College. ↩

- Dr Harris, who was a doctor of medicine of the University of Glasgow and a doctor of science of the University of Birmingham, was quoted in the Halifax Herald and later the May 2, 1913 edition of the CJT. ↩

- National Library/Canadian Jewish Times, July 4th, 1913. Vol XVI No 30, p5-7. ↩

- Canadian Jewish Chronicle, July 3, 1914, 11. ↩

- Canadian Jewish Chronicle, July 24, 1914, 11. ↩

- Maritime Museum of the Atlantic Halifax Explosion exhibit. ↩