Research offers an inside view of two indigenous schools closed by spring flooding and the concerns about accessing traditional food in Canada’s big cities

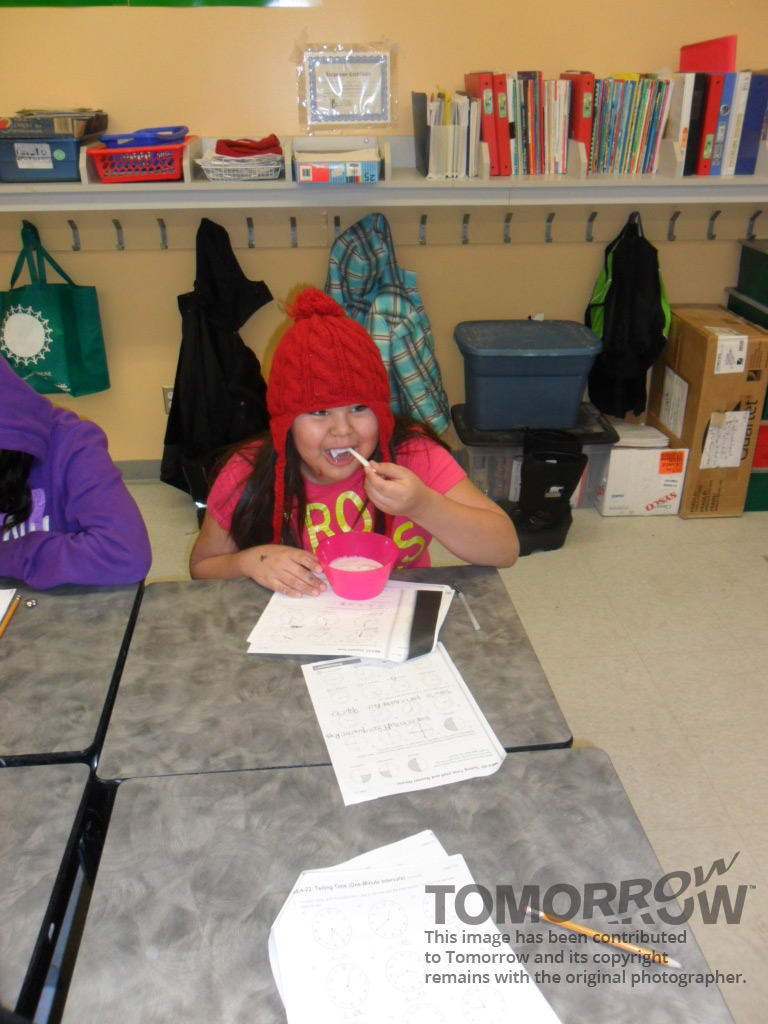

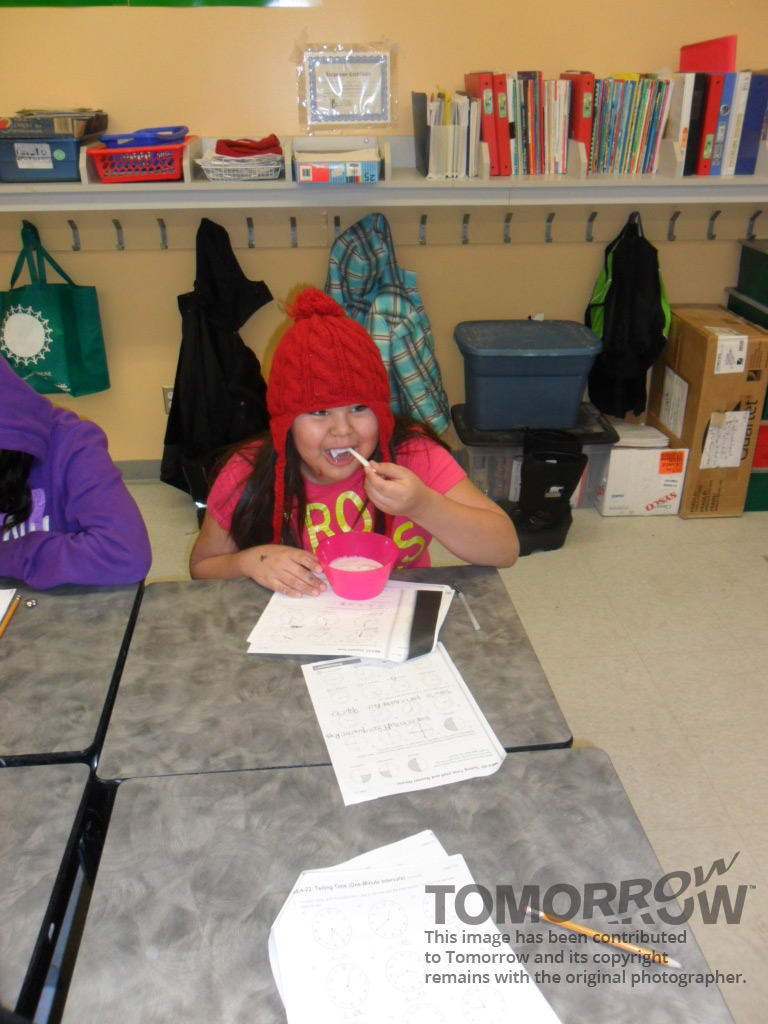

A pupil of St Andrew’s School in Kashechewan, Ontario, enjoys food provided by teachers.

This is the smiling face of a child in one of Canada’s most remote villages enjoying the extra food being provided to them by his teachers.

His school has been closed because of an ongoing emergency caused by spring flooding, sending sewage into basements and forcing the evacuation of hundreds residents of Kashechewan on the coast of James Bay in northern Ontario.

A total of 38 homes were flooded when a pump that moves sewage to the lagoon failed, leaving many of the buildings needing disinfecting and repairs, the school’s principal, Judy Stephen, told Tomorrow by email. Most of the families affected chose to be evacuated to Kapuskasing, including 61 of the elementary pupils.

As a precaution, families with children under the age of two, the elderly, disabled and prenatal women have been evacuated to Thunder Bay and Cornwall and another 300 are awaiting transport out, as of May 5. A “boil water” order has been put in place for those left behind, with water being flown to Kashechewan daily.

While the community waits for the emergency to pass, Tomorrow takes a look at a pilot programme designed to examine the benefit of snacks and the wider issues of health, food security and indigenous peoples.

This is the first feature in a series looking at the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous health, and the numerous studies which seek to find causes and solutions.

“Judy, I’m so hungry”

Mrs Stephen has been the principal of St Andrew’s School in the Cree community of Kashechewan for the past three years and has been married into the community for the past 30 years, starting her early career at the school in the late 1970s.

The school is in a young community, with 50 per cent of the population under the age of 25. There are 403 students currently, and another 55 joining in September, attending class in seven portables, with an additional three portables for administration, a computer lab and library.

Mrs Stephen recounts how one grade 7 pupil recently went into the office in the morning and said, “Judy, I’m so hungry”, and they gave him extra items from the breakfast programme, as had been done the week before.

“The teacher reports that when he does not eat, he is in a very difficult mood,” she says. “So the students are starting to recognise now that we are trying to be understanding of their needs and trying to be accommodating.

“So if the child doesn’t have his needs met or lunch provided in the classroom, he can come to me in the admin portable and get extra. And [they] also have that opportunity to eat without really disrupting what’s happening in the class.”

A pupil of St Andrew’s School in Kashechewan, Ontario, enjoys food provided by teachers.

Mrs Stephen says the needs vary for pupils in the school, with many families unemployed or seasonally employed and facing high costs of foods.

The community is 162km north of Moosonee on the James Bay coast. The nearest big store, Northern Store, in Moosonee, has recently put up its prices, claims Mrs Stephen.

A University of Waterloo pilot programme collaborated with St Andrew’s School and J R Nakogee School in Attawapiskat to provide snacks. Both communities are isolated and only accessible by air year round, boat during the summer and by ice road in winter and have been hit in the past week with flooding. Classes have been cancelled at J R Nakogee during the emergency while St Andrew’s have been moved.

Waterloo’s research in the communities has been part of wider work from the university over almost 20 years that also includes nearby Fort Albany.

Mrs Stephen says the snack programme and the work with the university was welcomed by pupils, teachers and parents, who have recognised the benefit to education from additional and healthier food.

“The programme was a positive way to have the kids begin the school day – they look forward to that time when they’re eating together,” says Mrs Stephen.

“It’s just been something that the staff and the students have recognised as positive in terms of meeting the needs of the students and achieving better results in terms of the attention span and the cooperation and the efforts of the students.”

“We are not being heard” – urban “hunger” for traditional food

Far to the west from these remote schools currently struggling with spring floods, the city of Vancouver has consistently been rated as one of the best cities in which to live. And it has a food problem.

Indigenous elders and youth join in a storytelling day talking about food security in Vancouver.

A survey involving indigenous residents from across Canada who now live in the city found frustration at being cut off from their traditional food and lifestyle.

Published in the Journal of Environmental Public Health, the study recruited 15 “youths” aged 19-30 and six elders and invited them to share stories about food and health. In small groups, the participants shared personal experiences, answering questions at the Aboriginal Friendship Centre in Vancouver.

The indigenous residents who took part expressed how health was more than just physical, and the food was more than simply nutritional.

Some suggested going back to their reserves “to learn and get traditional teachings”, but one youth said: “Mom did not like the negative things on the reserve, so that is why she kept me away from the reserve.”

“We need to learn how to live our old ways and new ways together, and still be successful as Native Peoples,” said one youth.

[Tweet “”We need to learn how to live our old ways and new ways together””]Loss of traditional knowledge was traced back to residential schools and the introduction of non-traditional foods, described by one youth as the “five white sins: flour, salt, sugar, alcohol, and lard”.

The storytelling event listed factors preventing access to traditional foods in Vancouver, including government policies, climate change, lack of connection between elders and youth, political representation, mixed cultures in the urban setting and the lasting effects of colonisation and assimilation.

It concluded that the access to those foods would improve holistic health – physical, emotional, spiritual and mental.

The study noted an overall desire to “heal from the past injustices of colonisation and assimilation”.

Youths and elders agreed a need for an indigenous voice in public policy making, giving rise to the title of the paper, “We are not being heard”.

It concluded that the storytelling method had “fostered a renewed interest and excitement about traditional foods, resulting in grassroots actions by the participants”.

Wind-dried salmon was brought by an elder to the storytelling event in Vancouver. Photo by Jen Castro.

Wind-dried salmon was brought by an elder to the storytelling event in Vancouver. Photo by Jen Castro.

Bethany Elliott is a project manager with the Provincial Health Services Authority in British Columbia and a co-author of the report, “‘We are not being heard’: aboriginal perspectives on traditional foods access and food security”.

The project started within the Aboriginal Health Department of the PHSA that was looking at chronic disease, where food security was flagged up as a concern. The population and public health unit then got involved, and aims to ensure more indigenous concerns on food are taken into account, explains Ms Elliott.

She says indigenous residents in the city access the conventional food system, but also the traditional food from their culture and home communities.

“Yes, there is lots of food in the city,” she acknowledges. “But how [do] we access that food? Is it affordable for everybody? Is it nutritious? Is the food that is affordable nutritious? If you can access a McDonald’s burger for a dollar, are you really meeting your nutritional needs? It’s really a question about health equity – who is getting the food and who has access to the food.

“Being indigenous people living in the city, it really is about more than just food. Food is really tied to culture and that is not something that’s unique to First Nations culture – that’s everywhere. Food is tied to your culture and your community and how we interact with people.

“In the city there is an added challenge of an increased cost of living, competing priorities for your time and attention, and some of our youth that came to the storytelling event grew up in Vancouver and really didn’t feel like they had a solid connection to their home communities.

“Aboriginal people in the city really do access two food systems. Incorporating their perspective is really important so we meet the needs of people who are living in the city and that it’s not just about getting your nutrient intake.”

Ms Elliott says the youth raised the problem of not having the opportunity to learn from elders in the city.

“It is connected to so much of the cultural practices in terms of how the food is prepared and the teaching that goes on and the gratefulness and thankfulness for what’s being offered,” she says.

“There definitely was an acknowledgement of the health disparities between aboriginal people and the general population. There are significant health concerns there.”

Contessa Brown, a member of the Heiltsuk Nation and resident of Bella Bella, British Columbia, was working at the Urban Aboriginal Garden Project in Vancouver when she met Bethany Elliott who asked if she could help recruit elders and youths for the study on traditional foods.

Contessa Brown, a member of the Heiltsuk Nation and resident of Bella Bella, British Columbia.

She says she made sure the 15 youths and six elders who took part were from across Canada, though all residents of Vancouver.

Ms Brown, who works as a family preservation/support worker for Heiltsuk Kaxla Child & Family Services, says indigenous people, particularly in the city, are missing out on access to traditional food, culture and even just family.

“We’re missing out on working together as a family on our traditional foods,” she tells Tomorrow by phone. “And also I think they’ve also recognised with the limited access to foods, what role the government play in our access to our foods.

“In the workshop they did recognise the difference on their health and that now they can look back and say that our people were eating a whole lot more healthier.”

Ms Brown says the youth came up with many ideas at the storytelling event, and while some go back to their home communities seasonally to work with traditional food, others started a Facebook page and plan to set up a trading post in Vancouver.

She says: “The urban aboriginal people still today do trades of food, even though it’s all by word of mouth.

“For an example, we harvest the seaweed and the people further up north work on ooligan grease and we don’t, so we do an exchange.”

Finding contemporary ways to trade – through social media or an urban trading post – can help, but is not to the same level as traditionally or in some indigenous communities, and is limited by provincial and federal legislation and regulation.

Ms Brown wants others to understand what the loss of access to traditional foods and why that needs to change.

“The government has played a role in the diminishing of our access to our foods, for example the salmon,” she says. “The salmon is diminishing now, as well as our herring because of the commercial [fishing].

“The loss of our cultural traditional foods is a big loss.”

Part of the loss of traditional food and ways on James Bay, as elsewhere, can be linked to past relocations of communities by the government. And in some of those places, basic access to healthy food is a problem.

The University of Waterloo’s study – “Assessing the impact of pilot school snack programs on milk and alternatives intake in 2 remote First Nation communities in Northern Ontario, Canada”, published in the Journal of School Health in February – found positive benefits of providing snacks, but considerable challenges.

The research was conducted over the school year from 2009 to 2010, four years after E. coli in the water forced the evacuation of 800 residents Kashechewan. It was also just before Theresa Spence became chief of Attawapiskat, most recently engaging in a high-profile fasting protest in Ottawa over indigenous rights and aligned to the Idle No More movement.

There are about 400 pupils at St Andrew’s School, aged pre-kindergarden to grade 8, and 108 students from grades 6 to 8 at the larger J R Nakogee School took part in the study.

St Andrew’s School, Kashechewan, Ontario, has been closed temporarily because of backed-up sewers due to spring floods.

Inside a classroom at St Andrew’s School, Kashechewan.

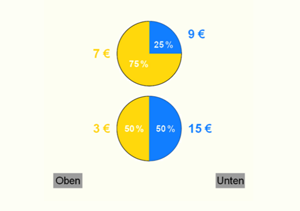

Pupils answered an online questionnaire before the pilot programme started to give a baseline. It found that in Kashechewan 74.4 per cent of the participating children were below the recommended intake for milk and alternatives in Canada’s Food Guide, and in Attawapiskat, 80.6 per cent of those who took part were below standards.

The pilot programme supplemented an existing fruit and vegetable programme in Attawapiskat, and improved the amount of milk and alternatives. But funding for such programmes is a long-term challenge.

After a week at Kashechewan, 62 per cent of pupils said they were motivated to eat healthier and several said they liked the programme because it was a time to socialise and because they were hungry when they got to school.

One said: “I like having food in the morning because I’m hungry.”

[Tweet “”I like having food in the morning because I’m hungry.””]Kashechewan struggled however to maintain the snack programme over the year because of staff issues and getting the supplemental foods into the community’s one store. After a year, pupils were even further below the CFG target for milk and alternatives such as cheese and yogurt.

St Andrew’s then principal, telling researchers he wanted to continue providing the snacks, added: “The kids are always hungry.” New sources of funding have since been found and a school food committee was set up to keep a snack programme going, they added. Both the researchers and school view this as a success.

The study said: “As food insecurity is prevalent, it remains a challenge to supply children with healthy food on a regular basis outside of school due to availability and affordability.

“The improvements seen in the short-term demonstrate the potential of such programs and should be seen as a first step toward addressing a greater number of factors affecting dietary behaviour.

“Unfortunately, the ideal circumstances of the pilot program often do not exist, and programs suffer when resources are lacking.

“Barriers included a lack of facilities and storage space, high food prices and a limited budget, environmental constraints and limited personnel.

“Schools having the resources required to initiate such programs may wish to investigate this as a viable way to improve the nutrient intakes of schoolchildren, especially in remote First Nations communities where the need is undeniable.”

A student at St Andrew’s School enjoys extra food provided by staff.

Rhona Hanning, professor at the University of Waterloo’s school of public health and health systems, says community-led school programmes can make a big impact on child obesity and improve general health. Ultimately, that can boost “health equity”.

She explains that “Canada’s Food Guide – First Nations, Inuit and Métis” allows for indigenous and culturally relevant nutrition options. But even then, students at the school were not getting enough milk or alternatives.

“Each community is extremely unique,” clarifies Dr Hanning. “The prevalence of over-weight and obesity is higher in the aboriginal community than in non-aboriginal community. There certainly is higher prevalence and that’s a tremendous concern for these communities because they see an earlier and higher prevalence of disease such as Type II diabetes and heart disease.

“The communities are very aware and concerned about these issues.

“There are inequities across Canada [such as] high levels of food insecurity, and this very much affects the food and nutrition intake for kids and often individuals within the community are quite frustrated because there’s not affordable access [to healthy choices].

“The communities definitely have significant concerns about access to fundamentals like healthy food to support optimum health and growth of children.”

One of the longer-running snack programmes along the coast of James Bay has taken a firm hold in Fort Albany.

Joan Metatawabin started teaching there decades ago and then married into the community, starting a food snack programme in the 1990s in the then residential school. She continued as student nutrition co-ordinator Peetabeck Academy where they have about 200 pupils, aged from a Headstart programme (1.5 years) to grade 12. With a large cafeteria and kitchen, it was easy to expand to offer morning and afternoon snacks each day.

“Fruit and vegetables were almost non-existent [here] 20 years ago,” she says in a phone interview. “There would be a few items came in once a week possibly, but they were extremely expensive.

“I had my own children at that time going through school, and as a teacher I realised that the majority of kids probably never got to eat those kinds of foods, because they were too expensive for families to buy, and also the quality was never very good.

“We just decided that maybe it would at least give them a serving of fruit a day, and it motivated the kids right from the beginning and it improved the attendance, the behaviour. They just started looking forward to having that half an apple or a piece of toast a day.

“It was an incredible difference in their attitude. And of course the staff just really thought it was the greatest thing because it helped them a lot in their teaching and the community got behind it too and realised it was important to do that.”

Mrs Metatawabin says the expense is the main barrier, particularly with larger families with five or six children as well as extended family all in the same home. The change from traditional foods such as wild meats and berries changed years ago to more western foods, she says. And an understanding of healthy foods has changed the demand for what the local store supplies.

“The people had already left behind that traditional lifestyle of going in the bush and trapping,” she explains. “They had already settled in this community and that was forced by the government, by the churches.

“The parents are doing a really good job with their children these days and they see the benefit [of the healthy snacks] now. I don’t think it’s so much that the parents don’t know or don’t understand [the benefit], it’s basically the price of it and the access to it.

“People were ready for this kind of change in food as opposed to what the local store – the Hudson Bay store and now the Northern Store – had been offering, the basic canned foods and not very much of the healthy foods.”

Mrs Metatawabin says having lived in the community so long, it helped convince parents of the benefits of healthy eating.

“I think the elders understand that the change in lifestyle, the change from traditional to this kind of lifestyle that they’re living now, has affected the health of people a lot,” she says. “They’re open minded and they realise that maybe changing the type of food you have to give your children is important.

“We still eat a lot of moose meat and caribou and we do a lot of bush things. We’re not giving up on any of that stuff. Our kids just love doing that kind of stuff. All those traditional foods that the grandparents had grown up with – and now these kids realise how important that is – it’s really good healthy food.

“Healthy food is kind of the main thing in our school right now – the kitchen is the focus.”

With the competing challenges of traditional and “western” food in Vancouver, the loss of knowledge in indigenous communities, both urban and remote, what does sustenance mean to the next generation?

Judy Stephen, at St Andrew’s School, says providing nutritious food is a challenge for their parents, through cost and distance. And with the flooding emergency that has evacuated around 200 residents, that’s made even harder.

“Some parents it’s a matter that whatever’s provided at home [the children are] still hungry, so they ate a little bit but not enough, and some the family is providing something but it might not be as nutritious or filling as it could be. It’s not enough,” she says.

“It’s quite a prohibitive cost, especially for the fresh fruits and vegetables. When you go into the store now and want to get a little pint of blueberries or strawberries, you’re looking at $6-7.

“And they have so many young children. People have a lot of mouths to feed. I don’t think we have any empty homes at all. We have some homes being built and right now it’s not uncommon to find 10-12 people living in a house that only has 2-3 bedrooms.”

As well as the school not now having working toilets during the spring crisis, Mrs Stephen says St Stephen’s is not even on a waiting list yet for a permanent building, which would allow larger refrigerator or freezer space to help snack programmes and offer more foods such as fruit and vegetables. Most of the portables were built to be used for five years, being opened in 2008. The school has tried to access funding where possible to offer the best choices for pupils.

“It’s something that has to be made more of a priority because we see that it makes a difference,” says Mrs Stephen. “The breakfast programme and the snack programme make a difference with the effort, attitude and overall school morale. It has added to our programming and the staff and students have recognised, ‘yes, this is a really good thing that’s happening in our school’.

The youth of Vancouver, Kashechewan, Fort Albany and Attawapiskat are looking for food sustenance, through tradition and nutrition.

“Like children everywhere, ours have basic needs that need to be filled,” says Mrs Stephen. “And in order to achieve in school, those basic needs must be met, and we want to collaborate with the parents, we want to support their efforts. It’s a matter of everybody working together and doing what’s right and doing what we know must be done in order to meet the basic needs of our children.”

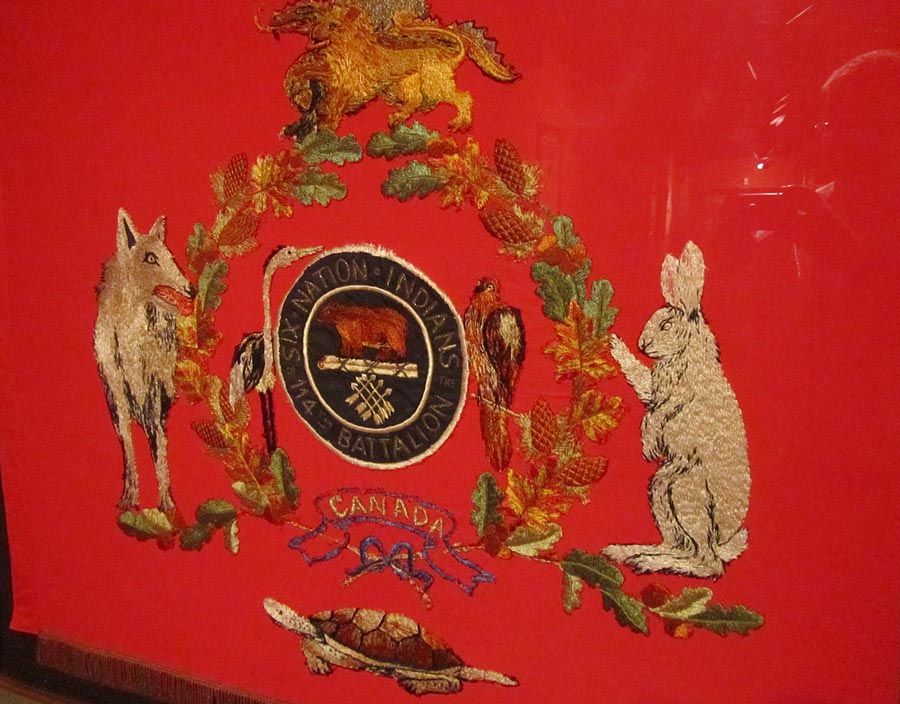

Tomorrow has been working on a series of features on indigenous health and we’d like to include more indigenous voices. We’d like to hear about your experiences with the health care system in Canada and particularly from anyone from Six Nations of the Grand River. Email us at istomorrow@gmail.com if you’d like to contribute.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.