What do museum objects mean to visitors, curators and the original communities from which they come? Artist in residence Jason Skinner explores different meanings. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

The current Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, Germany, is home to 500,000 objects from world cultures but isn’t on the map available for one euro at the airport, courtesy of Visit Berlin. The guards and staff in each room of the galleries tend to equal or outnumber the visitors.

The sheer vastness of the collection combined with its present out-of-the-way location is one of the main reasons for the move, come 2019, to the centre of the city and the tourist expanse of Museuminsel (Museum Island).

Tomorrow visited the current home, in Dahlem, in the city’s leafy southwest, to find out what is in the collection and how it is already changing before getting a new home.

Collecting like a “vacuum cleaner”

Curators certainly hope to increase the number of tourists at what will be called the Humboldt-Forum in the Berliner Schloss, the rebuilt residence of the Hohenzollern dynasty on Museuminsel. The Mitte borough island, just southwest of the Alexander Platz hub and a direct line down the Unter den Linden to the Brandenburg Gate has been the main destination for visitors since the reunification of Germany and Berlin. Dahlem has not.

Monika Zessnik is curator of the North American collection at the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Monika Zessnik, curator of the North American collection of 30,000 objects, says there were opportunities to consider the Northwest Pacific coast and Alaska indigenous communities from the perspective of the original collector, and also from the point of view of the modern heirs to the land.

The German-American anthropologist Franz Boas was one of many collector-donors who contributed to the Berlin collection, specialising in the west coast of North America in his early career. But the continent’s items are just a fraction of the half-million total. On top of the ethnographic and archaeological objects are 140,000 sound recordings, 285,000 photographs, 20,000 films and 200,000 pages of written documents, according the museum.

“The museum collected until the First World War like a vacuum cleaner – they took everything to Berlin,” says Dr Peter Junge, curator of the Africa collection.

The sheer number of items has largely prevented extensive research, he said. A curator at the Berlin museum began working on the 21,000 items from eastern Africa just two years ago.

Only a scratching of the entire collection is currently accessible online, as researchers filter through decades of inaccurate information and colonial and European biases.

Ms Zessnik says many items only have the collector’s name on the label, not the person or group who produced it or what ethnic group it might belong to.

Dr Junge says in one example from the eastern Congo, objects sold to European museums were labelled as being from a particular ethnic group, when the word translated from Swahili means to “these primitive countryside people”.

“There are so many steps to do to decolonise [an] anthropological museum, even the Berlin one,” says Dr Junge. “When you try to individualise the producer of the objects, you get a totally different image because anthropological museums always contain this colonial construction of Africa consisting of ethnic groups and ethnic groups are closed systems which produce art and have a religious system or family structure.

“And this is a construction and this construction is still very vivid in anthropological museums and it starts with these small steps, to say, ‘This object was produced by a workshop in the Bamileke area’ [in Cameroon], but it was not produced by THE Bamalik, because this is a construction’. [These are] very small steps which are very important to decolonise a museum.”

The perhaps assumed story of European powers pillaging countries of their cultural heritage is not quite so straight forward. Items were produced in many instances for the visitors from aboard, the equivalent today of offering souvenirs to gullible tourists. Modern tourists can easily outnumber staff researching the history of objects, and those items outnumber the visitors.

Dr Peter Junge is curator of the African collection at the Ethnologisches Museum in Dahlem in Berlin, Germany. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Dr Junge says that in the case of figurative tobacco pipes from the Cameroon grass fields, collected during colonial times, many were never smoked. Similarly, masks produced before the First World War were sold in “huge numbers” to colonial officers and collectors.

“Because of course African artists, or village heads, easily remarked what was interesting on the market so they produced objects for museums,” he says.

“There should be a lot of research done to find out what was made for museums. The idea of making objects for tourists, collectors, is not an invention of the 20th century.”

The Berlin museum collections are not simply historical items “taken” from what are referred to by museums as “source communities”. Many of the larger items in Berlin are models of boats or totem poles carved in materials that would not match originals in North America.

Ms Zessnik said one of their collectors, Norwegian-born Johan Adrian Jacobsen, reported that “all the time they are just selling objects – he’s aware that he had already been too late to get the real indigenous originals”. And sometimes objects were made for him, not simply taken from indigenous people to a colonial museum.

Dr Junge adds: “This is also one of these post-colonial constructions, having on one side the evil European colonialists and the other side, the Africans or Americans which are passive and sitting in the bush after having produced a mask and then somebody comes and steals the mask.”

The world’s hoard of historic objects

There is no estimate of the total number of objects from other cultures in museums and private collections around the globe, but as details emerge and questions are asked, there can be clashes between the institutions and descendants of indigenous communities from which the objects were taken.

In April it was reported that the Zuni in New Mexico were seeking the return of objects from the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, France, and the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin.

In April it was reported that the Zuni in New Mexico were seeking the return of objects from the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, France, and the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin.

The tribe has sought out ceremonial items more than many other communities, and has done so particularly from US institutions, which have a legal obligation to meet repatriation requests.

But many indigenous communities do not have the time or resources to explore historic collections half a world away, and many have more pressing concerns at home, particularly living conditions and health matters.

Dr Junge says the there is also rarely a fixed history of “source communities”, making communicating with and researching through modern nations all the more challenging.

“I think it’s a very European construction thinking source communities are something like homogenous group that have an eternal knowledge and everybody shares this knowledge, maybe some people more than other people,” he says. “They are part of historical processes.

“The traditional is not fixed – it’s changing. These simple constructions that there is a source community who knows everything and the objects are here and we just bring them together and then this is something like a healing process after colonial crimes – this is an illusion.”

Berlin has a track record of helping muddy the waters of history, hosting the Berlin West Africa Conference between November 1884 and February 1885, negotiating the future of the Congo River basin, home to many of the items in the city’s museum collection.

The Humboldt Forum on Museum Island in Berlin is due to be finished in 2019 and will house the Ethnologisches Museum. February 2014. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

The Humboldt Forum on Museum Island in Berlin is due to be finished in 2019 and will house the Ethnologisches Museum. February 2014. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Many of the objects currently in Dahlem were never intended to move again from their current home, such as boats, and will have to be placed in the 590 million euro Humboldt Forum before it is completed.

Some of the objects in the Ethnologisches Museum are so large they will have to be moved into the new Humboldt Forum before it is finished. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

A guide to the projects admits “expectations are high” and themes of the new displays wlll be ‘”the present,’ “multiperspectivity’ and ‘the audience'”. It will also feature visible storage, a now common approach in museums to show off more objects without giving the public any intimate access.

Dr Junge says the Humboldt Forum offers opportunities for the African collection, focusing on how the continent had much more contact with the globe long before its alleged “discovery” by Europeans. The Berlin collection includes Roman, Byzantine and early Islamic coins found in eastern Africa, as well as broken Chinese porcelain drawing a connection around the Indian Ocean.

The ethnology was a colonial construction of Africa as being a “counterpart to civilised Europe”, he says.

“It was more a projection of self-construction and we will focus on what is called entangled history,” says Dr Junge. “We will show how European history was very much entangled with African history.

“This is how we react to these post-colonial discussions, showing no longer that Africa is an exotic continent.”

Similarly Ms Zessnik says part of the process in developing the future of the collections is to “provincialise” Europe, demonstrating connections and the role of Europe during the period of colonisation, but also pointing out the connections that existed elsewhere [in the world – DELETE] long before and independent of Europe.

Visitors from around the globe might expect all the upcoming exhibitions to acknowledge the present; but bringing together people and objects of history is not simple.

Dr Richard Haas is deputy director of the Ethnologisches Museum in Dahlem in Berlin, Germany. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Dr Richard Haas, deputy director of the Ethnologisches Museum, says that even in cases where source communities work with the museum, the collections are so large that a few days is not enough to document everything.

He says the museum had a visit from two members of a tribe from central Brazil who were shown pieces from that tribe that curators hope to display at Humboldt.

“I asked them about these pieces – they couldn’t answer,” he says. “They don’t have the tradition. These pieces are 100 years [old]. They were curious to know some special things about pieces we are showing now, but they couldn’t say more than we have in our documentation because they are too young and the tradition is lost.

“If you work together with source communities, you have to know with whom you want to work who are aware of the tradition.

“In the case of Amazonia, we are expecting a group of Venezuelan indigenous people – this will be a project to. . . test to see if it’s possible to work together in the preparation or organisation of the Amazon exhibition in the Humboldt Forum.

“We try to do this but only in special cases. I think it’s not possible to do it for all exhibitions.”

Dr Junge says there are differences in the amount of contact with source communities depending on their role in their home nations. The bulk of the contact with Africa is through the King of Benin and the National Commission of Museums and Monuments, working with the “four or five biggest European museums”.

Talking to 200 former kingdoms would be impossible, and many would not be interested in working with museums. By contrast, there is more contact from North American and south Pacific communities, where indigenous communities “play an important political role within the country and they are also much more active addressing museums”.

“It’s impossible to write letters to every community,” he says. “In Africa, only our Benin collection we have these contacts. But this is for Africa still an exemption. The situation in Canada or Australia or New Zealand is completely different because of the political influence of these groups.”

He adds: “We have a lot of contacts and visitors. Many, many, many people come to visit the collection and they are very fond of finding all these objects here, but the discussion of doing joint exhibitions don’t play a big role in these discussions.”

The Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin includes displays that curators say is intended to show the colonial constructions about indigenous people in North America. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

The Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin includes displays of contemporary indigenous art. “Downtown Vancouver” is by Lawrence B Paul (Yuxweluptun), Coast Salish, 1987. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

The Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, Germany, includes a display of posters for films by the German director Karl May featuring the character Winnetou. The museum said this is to show the colonial constructions about indigenous people in North America. Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported

Ms Zessnik says indigenous artists and curators at a Northwest collections conference in Berlin were invited to contribute to the Humboldt Forum but had more pressing issues.

“They said, ‘Well we have our own things to do. As long as you keep them in a decent way and everything, it’s fine with us’,” she recounts.

“A lot of critics say we don’t talk to them – it’s not always like this.”

She says the collection, largely from the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, can be presented as how people lived in the past, or with photos and film of the present, but there is “not one single right way”.

“Cultures are different and the working approaches are different and when it comes to all this new museology and post-colonial theories, it affects our work, but maybe not in this kind of very strict way,” she adds.

“I think it’s also more about transparency,” she continues. “You should tell the public what you’re doing, who’s doing it and why you are doing it.

“If you go to North American or the Dutch museums, there will always be who was the curator, who was working on this exhibition, etc – that’s what we for a very long time didn’t do. German museums after the Second World War kind of said, ‘We’re not political institutions’, which is of course not true; of course we’re political institutions because we’re constructing, well, not truth, but different opinions.

“And that’s what we have to make obvious, I think.

“There’s still a lot of things to do, but I think the interesting thing also in Berlin is that you have a lot of interest groups here, constituent communities you can work with. Not every group is interested to work with us and that is also what we have to accept.”

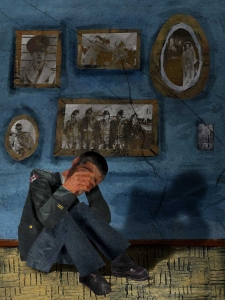

Moving towards the exit of the current museum’s home, there are film posters depicting the stereotypes of indigenous “Indians” of North America, colourful and animated but looking entirely dated. It is part of the task of looking back at the assumptions about the rest of the world and recognising the mistakes.

The number of objects, the way they’re exhibited, the role of today’s living descendants and the staffing and financial demands to put it all together are the invisible parts of the construction on Museum Island. That work remains behind the scenes in the quiet Dahlem site.

“Not every indigenous [group] has the same knowledge about objects still,” says Ms Zessnik. “I’m Austrian – if you asked me about objects here in the museum of European Cultures I wouldn’t be able to tell you about everything. So we need quite a lot of different knowledges. There are a lot of things still to be done, to be researched.”

– licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

– licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.