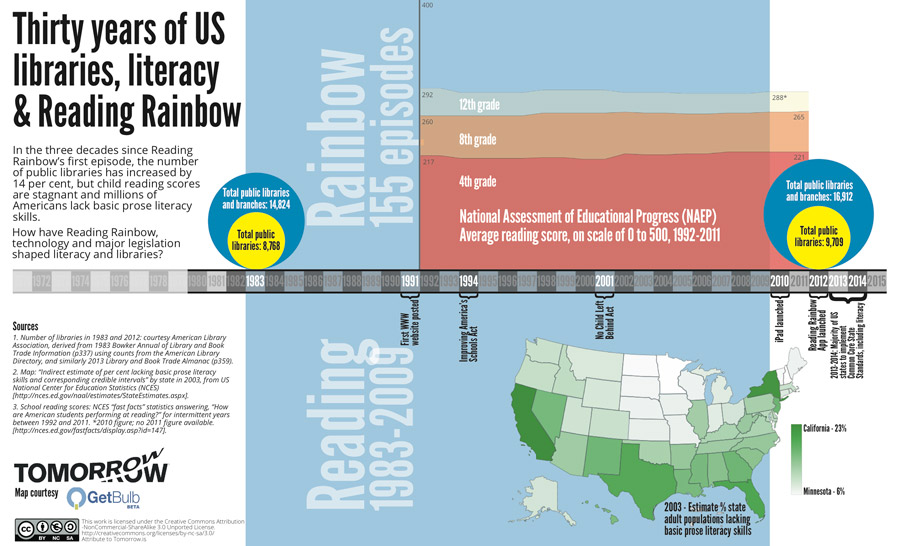

Research finds disparity, and tries to bridge the divide

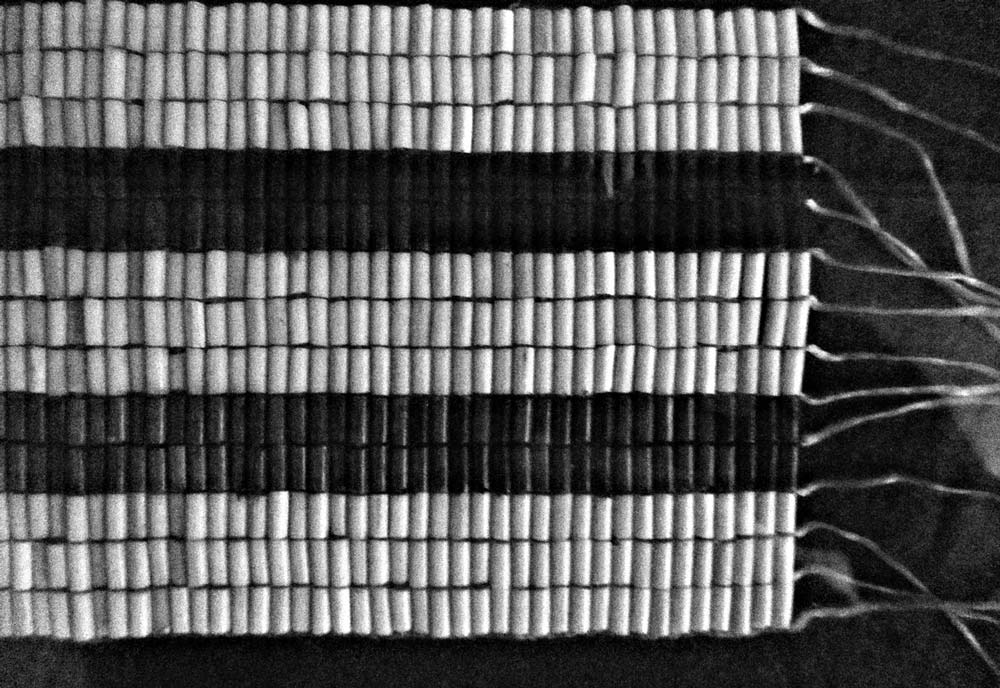

The two-row wampum belt was first presented to Europeans in 2013. This wampum is on display at the Woodland Cultural Centre, in Brantford, Ontario, Canada.

NOTE: The previous style of “indigenous” was incorrect and it should be Indigenous where the names of individual Indigenous nations are not available or reporting is of a broader nature.

FOUR hundred years ago this year, some of North America’s original peoples handed a belt to the Dutch.

The “two-row wampum”, made from shell and hemp cord, showed two purple lines separated by white, with more white on either side. For the Haudenosaunee Confederacy – then the Five Nations, now the Six Nations – it represented two societies living separate yet parallel existences. The original peoples of what they still call Turtle Island and the immigrants would be two brothers, two vessels travelling on the same river.

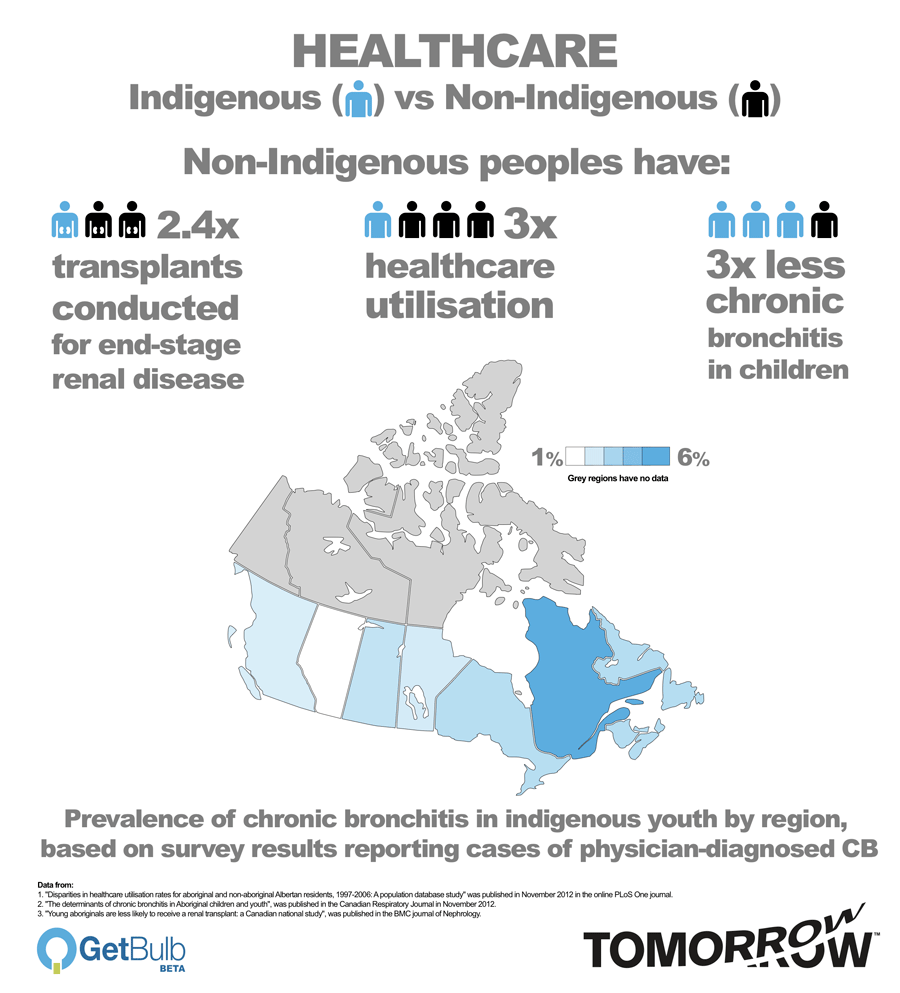

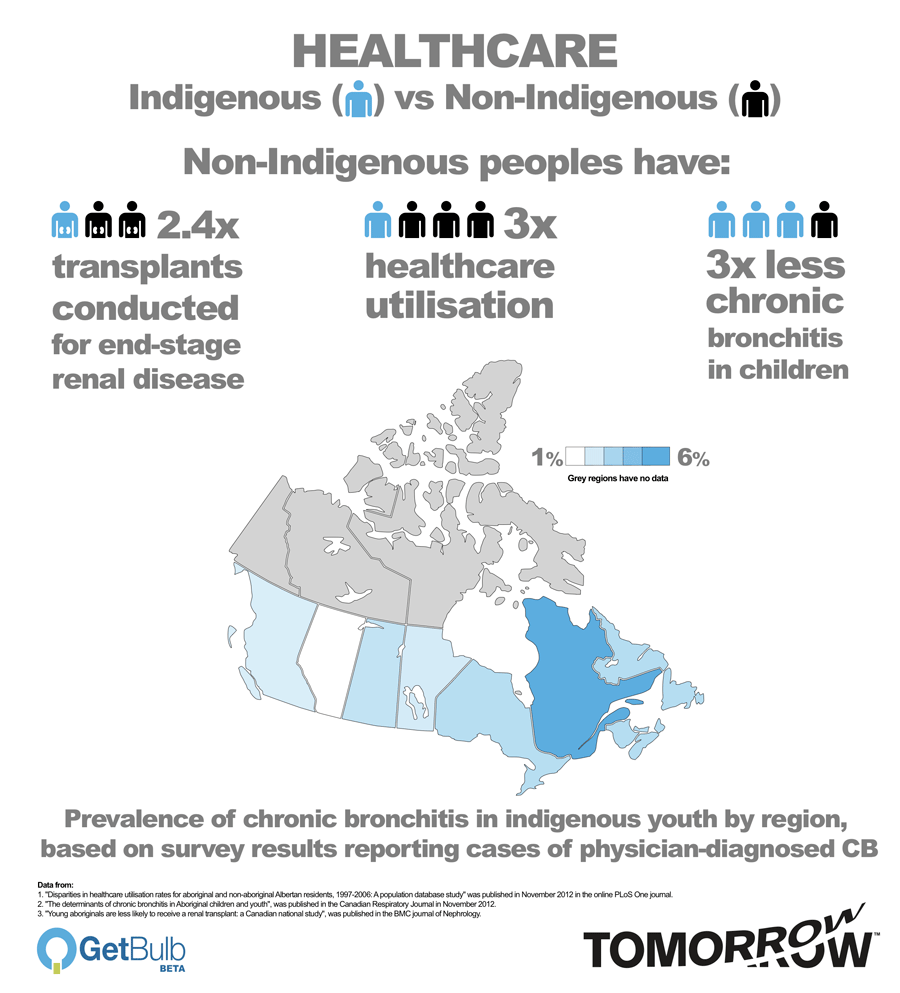

Today, in what is now Canada, the lines of Indigenous and non-Indigenous health are getting further apart, according to research by leading universities.

Health is worse, access to services is worse, and the opportunities to improve both are made more challenging by distance, funding, the law, government policy and history.

But pilot programmes are trying to address the gap, through training, mobile access and new arrangements for control of health services.

“In most of Canada, if you have an emergency, you call 911 and someone with a lot of training is dispatched to help you quickly,” said Dr Aaron Orkin, who co-authored papers on one of the projects in a remote part of Ontario. “In Sachigo Lake and other communities like it, if you call 911, nothing happens. You and your community, family and friends are left to your own devices.

“There’s an inequity and an injustice there.”

“We essentially are asking indigneous people to adapt fully to the way we do business, the way we deliver care,” said Dr Manish Sood, from St Boniface Hospital with the University of Manitoba, working to improve kidney disease rates. “Instead I think we need to change the model and try to adapt it specifically to aboriginal people.”

Tomorrow examined six pieces of research published in recent months – five of those papers being reported for the first time – and spoke to both scientists and communities about problems, solutions and opportunities.

In a follow-up to our earlier coverage of food security issues in Vancouver and northern Ontario for Indigenous communities and young people in particular, Tomorrow asks why are the two boats so far apart, and how will the injustice end?

“Concerning”: why are chronic bronchitis and kidney transplant rates worse?

There are a host of medical problems facing communities across Canada, but for some, the health needs are greater and the access to medical care is worse.

Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan are currently collecting data from the families of Beardy’s & Okemasis First Nations and Montreal Lake First Nation. There are respiratory problems in these communities, and the communities and academics want to develop interventions.

They are surveying the health issues in adults and children, as well as data on housing conditions, smoking, demographic information, medical history, social support and any residential school history in the family. They will then resurvey them in 2016 to see what might work from the solutions drawn up.

Dr Punam Pahwa, of the Department of Community Health and Epidemiology and the Canadian Centre for Health and Safety in Agriculture at the university, said the communities themselves are concerned about chronic bronchitis, asthma and sleep apnoea, and named smoking and housing conditions such as mould and damp as particular causes, said Dr Pahwa.

“We should be wanting the same health outcomes for young people, whether they are Indigenous or non-Indigenous,” she said.

Dr Pahwa and her colleagues originally started researching rural health, in the 2010 Saskatchewan Rural Health Study (SRHS), looking particularly at the causes of respiratory problems in farmers and small town residents.

Because the SRHS did not include Indigenous people, separate analysis was carried out based on the Aboriginal Peoples Survey 2006 by Statistics Canada and Indigenous organisations, looking at children aged six to 14 and adults aged 15 and up, particularly those living off reserve, Metis and Inuit.

In November 2012, researchers detailed how they found a higher prevalence of the disease in Indigenous youngsters.

The rate of the disease – based on doctor diagnoses that were volunteered by those surveyed in 2006 – increased with age, as well as with weight, lower income, the complications of asthma and allergies and living in urban areas. Certain areas had significantly higher prevalence of chronic bronchitis, with Quebec more than five times greater than Alberta.

The study stated: “Compared with our findings, the prevalence of self-reported physician-diagnosed CB was estimated to be 0.9% among Canadian children 12 to 19 years of age. Among Canadian Aboriginal adults, the prevalence of CB was found to be 7.2% among females and 5.0% among males.”

The study stated: “Compared with our findings, the prevalence of self-reported physician-diagnosed CB was estimated to be 0.9% among Canadian children 12 to 19 years of age. Among Canadian Aboriginal adults, the prevalence of CB was found to be 7.2% among females and 5.0% among males.”

But while Saskatchewan researchers are considering the causes of chronic bronchitis, work is well under way in neighbouring Manitoba to address a significant gap in getting kidney transplants.

Launched in March, the $1.6 million federally funded programme will see health professionals travelling to remote communities to screen on site for kidney disease, high blood pressure and high cholesterol and then direct them to appropriate services.

Again, research has found an inequity between the treatment Indigenous people get, and that for non-Indigenous Canadians. Young people are most affected, and the Indigenous community is generally younger. With more younger patients suffering from end-stage renal disease (ESRD), the healthcare gap could only get worse.

Dr Manish Sood, from St Boniface Hospital with the University of Manitoba and the lead author of a recently published national study, explained: “Because there’s a large growth of the young people in the aboriginal cohort, that’s going to be the group who’s going to be coming forward and facing kidney disease and kidney related problems.

“Young aboriginals would benefit the most [from treatment] because if they get a transplant at a young age they can live a healthy, productive life. And from a societal perspective living on dialysis is a very expensive therapy, there’s a lot of complications, [and] they have a worse quality of life.”

But while there are so many links in the “chain” of multiple steps to getting a kidney transplant, more work is still needed to determine where the problem lies. In the meantime, the new mobile project to Manitoba communities will make a difference, and be more cost effective.

“Part of the reason in doing this study was to see if anything improved or changed in the past 10 years, and we found none,” said Dr Sood. “We hope that this research will serve as a bit of a rallying point for advocacy.

“This kind of study hasn’t translated into policy changes. To be honest, that’s concerning.

[Tweet “”This kind of study hasn’t translated into policy changes. To be honest, that’s concerning.””]”Some early evidence says they’re referred just as much. But once you get referred you need to have multiple appointments and multiple tests done – heart scans, ultrasounds of the belly, many blood tests done, psychological testing – to make sure that you’re going to be able to succeed when you get the transplant.

“These things involve separate appointments and testing. If you live 200 km away, you have child care issues, you have socio-economic issues, how easy is it going to be to travel back and forth and get all these things done to ensure the process of making yourself ready to receive the transplant medically is performed?”

Researchers looked at the statistics of more than 30,000 Canadians between 2000 and 2009 found Indigenous patients were significantly less likely to receive a kidney transplant.

The data of 30,688 dialysis patients – 2361 of them Indigenous – revealed an even more marked gap in young people. Overall, the need for transplant and dialysis is four times higher in the Indigenous community.

Worse, for those aged 18 to 40, 48.3 per cent of caucasians received a transplant, compared to 20.6 per cent of Indigenous Canadians – less than half as likely. The gap decreased with age group, even after accounting for the lower life expectancy differences.

Researchers concluded: “The results of this study, coupled with the rapidly-growing population of young Aboriginals in Canada, suggests that the significantly reduced rate of renal transplantation in the young Aboriginal population may continue to play a significant role in the burden of chronic disease and resultant health challenges they face if some degree of targeted intervention is not undertaken.”

Is the problem as simple as taking healthcare services to remote communities? Other research has found Indigenous peoples are not accessing care at all.

Who is getting treated? Why Albertans don’t go to hospitals

Indigenous peoples in Alberta, who have a lower life expectancy and higher rates of some diseases, are consistently not taking up healthcare services, even when nearby in cities such as Edmonton and Calgary.

A study from the University of Alberta looked at the rates of two million Albertans using cardiology and ophthalmology services in the province over a nine-year period.

Divided into three groups – “federally registered Aboriginals”, individuals receiving welfare, and other Albertans – it found utilisation rates for Indigenous populations “significantly” lower than the non-Indigenous group and both were below those on welfare.

Healthcare insurance and hospital utilisation information were used to look at when services were used, and then Indian Act distinctions applied in terms of who was “status Indian” compared to the rest of the population. This means non-status Indigenous Métis or other residents might be considered part of the general population, thereby distorting those utilisation rates, making the potential gap even greater.

Figures from the survey found 0.28 per cent of Indigenous Albertans used cardiology services, compared to 0.93 per cent for other Albertans, more than three times higher. Those on welfare used services at a rate of 1.37 per cent, almost five times higher.

The gap remained largely consistent over the nine-year period surveyed, suggesting the problem of use of healthcare services is a long-standing one that has yet to see improvement.

Researchers concluded that the higher rates for those on welfare implied that poverty or economic factors alone could not explain the disparity. There was also no major differences found depending on the distance from Edmonton and Calgary, so geography could not be a significant factor.

The study, published in November 2012, considered two thirds of the 3.29 million [2006] population in Alberta, the country’s most affluent province and highest per capita for healthcare spending.

The study stated that a cultural difference to healthcare might be a factor, where “Western individual autonomy” contrasts with “integration of the family or community group into decision-making”.

“Consequently,” it continued, “conventional health professional teams may represent a barrier to Aboriginal healthcare utilisation. A second potential factor relates to the long history of maltreatment endured by these Aboriginal adults and children, resulting in a deep distrust of institutions and potentially profound effects on the likelihood that individuals seek voluntary treatment.

“If healthcare utilisation rates reflect the contributions of multiple factors, increasing the number of Aboriginal healthcare professionals coupled with increasing cultural sensitivity amongst non-Aboriginal health professionals may prove effective approaches to begin addressing the differences observed.”

But boosting the number of healthcare workers or cultural sensitivity can be a political matter. And the politics governing Indigenous health are as complicated as the medical problems.

Caught between a rock and the Constitution

Whatever national trends there may be in health disparities across Indigenous communities, there are also countless variations depending on the health funding they receive from the federal government and the standards and services delivered on the provincial level.

Each community is caught between the laws that dictate who runs health services and laws that dictate who runs Indigenous communities.

Section 91 of the Constitution Act 1867 specifies that “the exclusive Legislative Authority of the Parliament of Canada” extends to a number of areas, including subsection 24, “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians”. Meanwhile, Section 92(7) reserves for the provinces “The Establishment, Maintenance, and Management of Hospitals, Asylums, Charities, and Eleemosynary Institutions in and for the Province, other than Marine Hospitals”. The provinces are responsible for health care delivery for its citizens, but the federal government is responsible for Indigenous healthcare.

The Indian Act 1985 states that “all laws of general application from time to time in force in any province are applicable to and in respect of Indians in the province”. So, the provincial or territorial health standards apply, even though the federal government has exclusive jurisdiction over “Indians, and the Lands reserved for the Indians”. The federal government adopting provincial standards and applying them automatically is known as being “incorporated by reference” or “referential incorporation”.

Health Canada, under the Canada Health Act, provides different levels of healthcare funding to individual Indigenous communities, and has left standards to the provinces, who have jurisdiction, while still controlling the purse strings.

In one example provided to Tomorrow by an Indigenous person in Alberta, changes to provincial health services create financial challenges that are paid for out of federal funds.

When the province centralised dialysis treatment for kidney patients, a drive of 1-2 hours became 6-10, with the remote community buying a van and hiring a medical transportation driver to take residents for treatment. Being given responsibility for healthcare, without money to match, means a continual clash between provincial services and standards and federal funds, he said. And because the federal government simply applies the provincial standards, “incorporated by reference” to “Indians, and the Lands reserved for the Indians”, they have to fund rules they had no hand in making.

Officially, Canada has set the goal more than once of closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in standards of living, particularly health.

The 1996 report from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples called for reform of health and healing systems, including passing “the levers of control to Aboriginal people” and “bring equality in health status to Aboriginal people”.

The four-point strategy called for:

“1. Reorganisation of existing health and social services into a system of health and healing centres and healing lodges, under Aboriginal control.

2. A crash program over the next 10 years to educate and train Aboriginal people to staff and manage health and social services at all levels, in Aboriginal communities and in mainstream institutions.

3. Adaptation of mainstream services to accommodate Aboriginal people as clients and as full participants in decision making.

4. A community infrastructure program to deal with urgent problems of housing, clean water and waste management.”

At the time, the report said there were just “40 to 50 Aboriginal physicians” and 300 registered nurses, both just 0.1 per cent of the total of those professions.

In 2005, “First Ministers and National Aboriginal Leaders Strengthening Relationships and Closing the Gap” – a deal with Liberal Prime Minister Paul Martin that became known as the “Kelowna Accord” – promised $5.1 billion over five years, including $1.315 billion to reduce infant mortality, youth suicide, childhood obesity and diabetes by 20 per cent in five years, and 50 per cent in 10 years. It also pledged to double the number of health professionals by 2016 from, then, 150 physicians and 1200 nurses.

The need for doctors in 2008 was reported to be 2000, but Canada had just 200.

Some opposed the Kelowna agreement, arguing that the provision of services could not be separated from Indigenous and treaty rights, and that the deal was a continuation of government assimilation attempts.

After his government fell, Paul Martin introduced a private member’s bill to implement the accord, but the Constitution Act 1867 – the same act that confused healthcare and Indigenous issues in the first place – prevents a private member’s bill from spending public money.

Regardless of its strengths or flaws, the Kelowna Accord was never passed into law, nor were its spending targets met. Instead, health funding was capped starting from 1996-1997 at 3 per cent, while the number of Indigenous peoples in Canada who were covered by provincial standards and federal funds increased dramatically.

In a pre-budget submission in 2011, the Assembly of First Nations identified a $805 million shortfall over five years in the Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) Program, caused mainly by tens of thousands of new registered Indigenous peoples in Canada, stemming from court challenges.

That did not include other budgets that impact on health. Education moneys might be used to provide snack programmes in remote schools, or infrastructure funding could provide better housing and, in turn, reduce health problems from mould and damp.

Health Canada did not reply to requests for comment for this feature.

Nearly 10 years on, the only remnant of the Kelowna Accord was the follow-up, the “Transformative Change Accord” in BC, with a health plan a year later.

Come October 1, Indigenous health programmes will fall under the control of the new First Nations Health Authority (FNHA), with $2.5 billion being transferred over five years to pay for services previously delivered by Health Canada, including dental care, prescription drugs, counselling and medical-related travel for about 127,000 Indigenous people in the province.

In neighbouring Alberta, Treaty Six is the only one of the three in the province that explicitly mentions health in writing. It states: “That a medicine chest shall be kept at the house of each Indian Agent for the use and benefit of the Indians at the direction of such agent.”

But all 11 treaty areas across the country draw a similar understanding of the relationship with the federal government on healthcare based on the spirit and intent of the treaties.

The Health Co-Management (HCOM) Secretariat in Alberta relies on federal funds to run health services on reserves, but the Government of Alberta was slow to join the table, even though they set the standards and centralised services that apply to those reserves.

In Six Nations in Ontario, home to the two-row wampum, their understanding of federal responsibilities encompasses the idea of “perpetual care and maintenance”, stemming from but not directly stated in the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784.

There are a multitude of treaties, arrangements, court cases and ambiguities that have complicated the political, legal and financial situations with health in Canada. In January 2013, the Federal Court ruled that 400,000 non-status Indians and 200,000 Métis were covered under section 91 of the Constitution Act 2012, adding to the further complexities of the provincial and federal health relationships. All those interactions continue to evolve.

One of the newer arrangements is the Health Co-Management (HCOM) Secretariat in Alberta, running the health service on reserves in Alberta as a joint agreement between the federal government and the three treaty areas of the province, Treaty Six, Seven and Eight.

Peyasu Wuttunee is the coordinator of the body and a member Red Pheasant, a Treaty Six First Nations.

Mr Wuttunee said more control over health helped improve health targets for Indigenous communities.

“First nations know what their communities want and need,” he said. “So for the same dollars, first nations can deliver better services and better in terms of higher utilisation, higher community buy-in, versus those same dollars than the feds can do with it.”

“Health outcomes for first nations in Alberta need to be improved, because if you look at any of the stats, you’ll see they’re significantly worse, than the rest of the population.

“It is a slow process and the whole issue of trust is a fairly major element to the work.”

Do Indigenous peoples in Canada have time to wait for the process – or the constitution – to change?

Helping yourself, not waiting for others

One of the four changes that the RCAP called for was increased training in healthcare for communities, something that can be life-saving in the most remote areas.

Community first aid or community first response course participants carrying an injured patient in a programme simulation at Sachigo Lake, Ontario.

Sachigo Lake, with a population varying seasonally of around 400-450, lies 425km north of Sioux Lookout and southeast from the Manitoba border, accessible by plane, year round, or ice roads in winter.

There is a nursing station, funded by Health Canada, generally staffed by three nurses and community health workers. A family physician, based in Sioux Lookout, visits Sachigo Lake for 3-4 days a month. In an emergency, transport is provided to medical facilities in Sioux Lookout, Thunder Bay or Winnipeg which are about four hours away, at best.

The community has been home to unique first aid training since 2009, rewriting the rules and giving residents the confidence to deal with anything from emergencies on hunting trips in the wilderness, to mental health problems.

Various basic tenets of first aid training – such as stabilising a patient or not moving a patient until a medical expert arrives – are impossible in the wilderness. And in such a small community, almost anyone offering treatment knows the patient, adding to the stress of the situation.

Jackson Beardy has been the health coordinator for the Sachigo Lake First Nations for the past five years and was a co-author on two research papers about the courses.

He said first aid training has been available to members of the Canadian Rangers program and others in the community but said more residents needed the skills. The programme offered by the study was ideal to what the area needed, said Mr Beardy.

Speaking to Tomorrow by phone from Sachigo Lake, he said: “When we have an emergency crisis here, we don’t have the ambulatory services that we would require to tend to the victim or for that matter to have the nurses coming out from the nursing station. The nurses are not permitted to leave the premises, so they would have to wait until somebody brings them to the nursing station.

“With the training that we had we are able to teach our community members what the protocol would be in transporting and treating the victim before we have them at the health facility.”

Mr Beardy said other communities in northern Ontario want to have the specialised first aid training.

He added: “When we have an emergency crisis, whether at the residence or if it happens out on the land, we don’t have the services that we need. To have such a programme, we are able to care for our community at that level.

“If remote communities had medical supplies readily available, it would be beneficial. Other than what we have at the nursing station, we don’t have access to them.”

[Tweet “”If remote communities had medical supplies readily available, it would be beneficial.””]Twenty people took part in the first “community first aid or community first response” course, which had to take into consideration that there is almost no such thing as a “complete stranger” in Sachigo Lake. Treatment would most likely be provided by a family member, friend, colleague or someone else known to the patient.

The course has been repeated since and researchers said tailoring first aid training to a community with specific needs could be replicated anywhere.

“Teaching wilderness first aid in a remote First Nations community: the story of the Sachigo Lake Wilderness Emergency Response Education Initiative” was published in the International Journal of Circumpolar Health in November.

It included very frank feedback from those who took part in the training.

Community first aid or community first response course participants and researchers teaching and learning first response in a circle outdoors, at Sachigo Lake, Ontario, in 2012.

“Doing CPR on [a] baby reminded me of when they did this on my 2 month old granddaughter,” said one individual. “They took her and were doing it on the washing machine. I didn’t know how to do that.”

Another recounted: “Everyone goes out alone. That’s what happened to my grandpa once. He dislocated his [points to hip] he was out in the cabin … he managed to crawl out to his boat, crawl up the hill.”

A third pointed to the value of local knowledge when someone is out in the wilderness: “The upbringings … the teachings of our parents and grandparents. Be self sufficient in all aspects of life.”

The paper also found that there were concerns about access to healthcare from the nurses station, particularly with restrictions on painkillers because of “prescription opioid abuse and misuse”.

Dr Aaron Orkin, a co-author of the paper and an assistant professor at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, said that writing a new first aid programme, from the ground up, was about ensuring that remote Indigenous communities had access to training that suited their place in Canadian wilderness areas.

Though many people in the community had some first aid training, it was not in the context of remote locations where “help” was on its way.

Course material, down to the CPR protocols used, was rewritten based on primary medical literature to suit Sachigo Lake.

The course also considered the “shared knowledge” about a patient, for example, if a group of friends are on a hunting or fishing trip.

“We emphasised making use of conversations that can happen around the patient,” said Dr Orkin. “Emphasising how care provided by teams or by communities as opposed to by collections of individuals is key to that community orientated first aid approach as well.”

Mental health first aid – a vital part of building confidence

During the second course, a half day was set aside for mental health first aid, to consider both patients who may have mental health issues such as substance abuse or suicidal thoughts, and the bonds formed in such a small community.

Community first aid or community first response course trainers returned to Sachigo Lake in February 2013 to do community presentations and wrap up for the pilot project at the Sachigo Lake Fishing Derby, one of the largest regional gatherings each year.

Jackson Beardy said it was the most useful part of the course. Family members and friends often “flock to the site” of an emergency and protocols for addressing a mental health issue come into play.

“The community is more self-sufficient with the knowledge or skills that the community members are getting,” he said.

The mental health section was delivered by Dr Baijayanta Mukhopadhyay, who is based in northern Ontario, and was recruited to the project in its second phase as a medical resident for his interest in mental health issues. He said he was concerned there was a “bit of a revolving door issue” where residents in the region were being treated and sent home, only to return again later.

He said: “A lot of people feel at a loss when confronted with a mental health issue or mental health emergency.

“People probably have a little bit of an idea of what to do if someone doesn’t have a pulse or isn’t breathing. But when someone is acutely suicidal, I think people get intimidated, not sure what to do, afraid of saying the wrong thing.”

Dr Mukhopadhyay said there were three key elements to the mental health instruction: keep yourself safe, get help, and listen. But most people don’t have the language to deal with mental health issues, thinking they need a specific clinical diagnosis when first dealing with an emergency.

“Getting people comfortable with different sorts of mental health crises can actually be empowering,” he said.

“Just like there’s lots of reasons why someone might not be having a pulse or might not be breathing, the critical point is to recognise is that they don’t have a pulse and they’re not breathing. There is the same principle of bringing mental health crises into easily understood syndromes so that people just need to recognise one thing that might be dangerous.”

Dr Mukhopadhyay said mental health first aid should be a part of general training, as well as that for remote communities.

“Part of that is just to demystify a lot of mental health issues,” he said. “Remote communities have particular challenges, but one of the strengths they have is that they tend to have a lot of support by a network of family, friends, local institutions.”

Can the two canoes talk to each other?

Away from the remoteness of the north, in more urban parts of the country, when emergency or specialist healthcare services are needed, Indigenous peoples enter a non-Indigenous system. Are they getting what they need and do they understand the treatment options presented to them?

Dr Yvonne Boyer has been a board member at Minwaashin Lodge – Aboriginal Women’s Support Centre in Ottawa for seven years and is a Métis lawyer and academic at the University of Ottawa specialising in Aboriginal and treaty rights.

She said “very few” Indigenous people, particularly women, have been well treated by the health profession. If there are two women with their children in hospital waiting to see a doctor, the “white folks” will get seen first. “Guaranteed,” she said. “There’s racism everywhere you go.”.

She said women “won’t and can’t” speak up because they’ve been oppressed their whole lives, often coming out of hellish situations or forced into working on the streets. There are also mental health issues, addiction problems and others, all stemming “from the results of colonisation” and the legacy of residential schools, she said.

Dr Yvonne Boyer

Dr Boyer is a co-author on a planned research study on “shared decision making”, between the lodge and a PhD candidate at the University of Ottawa’s Institute of Population Health, Janet Jull. The project will consider how Indigenous women make health and social decisions about their health care.

In the published protocol for the project, titled “Shared decision-making and health for first nations, Métis and Inuit women”, it outlines trying to address whether a barrier to health utilisation and better health for Indigenous women hinges on their interaction with doctors, nurses and other healthcare providers. Decisions are meant to be made together in a “collaborative process”, under the concept of shared decision making.

The study will have three phases, reviewing other studies and what strategies are effective, followed by interviews with 10-13 Indigenous women, and then creating a guide for shared decision making and putting it through focus group and usability testing.

Dr Boyer said that some of the racism is intentional, but racism can also be ingrained in the institution, even when its individual employees don’t realise it.

“A lot of it has to do with education,” she continued. “It’s something that’s been perpetrated throughout an institution that this is the way these [Indigenous] people are treated and people often don’t question it.

“We do have a big problem with aboriginal health today. So obviously what’s been working, hasn’t proven to work.”

Dr Boyer said the history of residential schools, affecting parents, the children who were removed and three subsequent generations, has contributed to the physical, mental and emotional health problems seen in the women and children who are helped at the lodge.

She said: “The healthcare system is trying to respond. I don’t think they’re going quick enough or asking the people what will work for them. It goes back to the people at the head of the system thinking that they know what is best for aboriginal peoples. And that goes back to the whole guardian-ward theory.

“It’s the paternalistic theory that aboriginal people don’t know enough to be able to make decisions on their own so the white folk’s gotta make decisions for them. And then it doesn’t work.

“If you engage them in some dialogue and they make the decisions and develop the programmes right at ground level, they know often what’s wrong.”

[Tweet “”It’s the paternalistic theory that aboriginal people don’t know enough to be able to make decisions on their own””]But Dr Boyer said the project to developed shared decision making for Indigenous women would give them a voice where traditionally they have felt powerless with the medical profession.

She said: “I do see positive things happening. We’re all people. Aboriginal people are not biologically inferior to non-aboriginal people, but there are historical reasons why there’s such a huge gap in aboriginal health. What can we do together to address some of these problems?”

Janet Jull, from the university’s Institute of Population Health, who will lead the project for her PhD, said her background as an occupational therapist and early employment in Nunavut where she found significant health problems, pushed her to this new study.

She said: “How do you ensure people get the information they need to be able to make an informed decision?

“There’s all kinds of barriers.”

Ms Jull said she didn’t think withholding of information was deliberate, but healthcare officials might not be aware of how they relate to people with different “worldviews”.

While western medicine might be “miraculous”, shared decision making is about an “equitable partnership”, she said. A healthcare provider might be more directive in their advice to someone they perceive as not making the “right” decision.

“Each of those healthcare clients is entitled to know what their options are,” she said, “what their risks and benefits of those options are and what the chances of those risks and benefits are so they can make the best choice for themselves.

“That’s their right.”

The two boats on the river might be talking to each other, but do they understand each other?

Two boats on the river

At Six Nations of the Grand River, 400 years after the first two-row wampum was presented to the Dutch, their challenges are not caused by such factors as distance from big urban centres or a lack of training.

A pilot study lead by McMaster University instead found low “walkability, street connectivity, aesthetics, safety and access to walking and cycling facilities” as key issues.

The small number of people interviewed with the project all bought groceries off-reserve, though fresh fruit and vegetables were said to be “available and affordable both on and off-reserve”, though less so on reserve. Ninety per cent of the 63 people who took part said tobacco was a problem and was readily available to children and young people. Three per cent said they would accept more tax on tobacco as a solution.

Among figures published in the paper:

- 22 per cent grew their own fruits and vegetables in the summer

- 74.6 per cent said there should be a ban on tobacco advertising, but were not in favour of taxes to reduce tobacco use

- $151 per week on average was spent on groceries per family, compared with the Ontario average of $140 per week.

Overall, interviewees said they were satisfied with their community, but also recognised there were future health problems facing young people.

The paper concluded: “The future health of Six Nations depends on the community’s involvement and ownership of new initiatives to target maladaptive health behaviors [sic].”

Dr Sonia Anand is a professor in the department of medicine at McMaster University and director of the Chanchlani Research Centre at the institution.

She was the senior author on the paper, which included four co-authors working for Six Nations Health Services based in Ohsweken, Ontario. Nobody from the Six Nations was willing to comment to Tomorrow about the study or the Two-Row Wampum over four months of requests.

Dr Anand said a previous study in 2007 worked with families in Six Nations but concluded that future work needed to look at the community as a whole, rather than just at individual behaviours.

“Tobacco is a complex issue,” she said, as an example. “It is the number one employer and revenue generator, and has traditional uses.

“[The community] was traditionally highly physically active. Today tobacco is over-used, the majority drive off reserve [to buy food] and physical activity has a number of barriers. It is not unique to the first nations community.

“I think the Six Nations have some of the same challenges of other urban communities, but also some unique ones.”

Equality or Equity? Getting the boats to the same destination

There is a healthcare problem in Canada for Indigenous peoples, and there are research programmes and pilot projects working to change that. New experiments in administration are underway even as the political canoe, on a federal level, remains almost entirely dead in the water.

Both researchers and those involved in healthcare told Tomorrow the issue is about “equity” – the two boats must arrive at the same destination.

Peyasu Wuttunee, of HCOM in Alberta, said the more they work with others, the more likely they are to find success.

“It’s important that people recognise that the health outcomes are still not where they need to be, that community and leadership are serious about improving health outcomes – there’s not one linear path to that,” he said.

“One can’t ignore the history of the relationship, so the residential schools, the abuses there, the prohibition on language and culture, the efforts to strip that away have taken a toll.

“It’s not a quick fix and it’s not an easy answer. It took us a long time to get to this point; it won’t be a quick fix overnight.

“The effort is there and sometimes progress is slow, but there’s a human toll to that slow progress, so that can’t be underestimated. This is a pressing issue and it’s not okay that these outcomes are the way they are.”

No issues for principles 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 or 10.

1. Freedom of expression and 2. Accuracy: This is a joint issue. Tomorrow has a duty to report and, with many of these research papers not getting other media coverage, deserved attention. But the feature has been delayed by at least four months because it was vital to find Indigenous voices for their perspectives on research which directly relates to them. Individuals and communities were contacted, sometimes repeatedly, seeking voices. Most did not reply and one said the entire treaty organisation was “not allowed” to speak to the press. Under principle 11 (promote responsible debate and mediation), is the reporting less accurate because people will not contribute their voices? Should those communities themselves be the only ones to report on news as opposed to those outside? Tell us what you think.